The Chemistry of Truthfulness

Our fascination with truth serum owes its beginnings to UW psychiatrist William Bleckwenn.

In Quentin Tarantino’s 2004 film Kill Bill (Volume 2), Bill (played by David Carradine) seeks answers from The Bride (Uma Thurman).

“I’m going to ask you some questions, and I want you to tell me the truth,” says Bill. “However, therein lies a dilemma, because when it comes to the subject of me, I believe you are truly and utterly incapable of telling the truth … [and] I am truly and utterly incapable of believing anything you say.”

“How do you suppose we solve this dilemma?” asks The Bride.

“Well, it just so happens I have a solution,” Bill replies, shooting her with a truth serum-filled dart he calls his “greatest invention.”

We’re all familiar with truth serum. In popular culture, it’s how we get information from prisoners and people otherwise unwilling to spill the beans. In True Lies, truth serum leads Arnold Schwarzenegger’s character to reveal his escape plans to terrorists. It makes Whoopi Goldberg say exactly what she’s thinking to everyone she meets in Jumpin’ Jack Flash. The truth serum in the Harry Potter series, Verita-serum, is so powerful that the Ministry of Magic strictly controls its use. Three drops of the colorless, odorless potion are enough to make anyone spill his or her innermost secrets.

People tell lies big and small all of the time. But humans are remarkably bad at detecting deception — despite numerous theories on the behavioral tics of liars, from fidgeting to sweating to avoiding eye contact. So the popular and scientific appeal of a truth serum is not hard to understand.

The use of a chemical to induce people to tell the truth was first tested in the 1920s by UW psychiatrist William Bleckwenn. His experiments with narcoanalysis — or psychotherapy conducted under the influence of drugs — laid the foundation for the modern field of psychopharmacology and sparked international interest in the power of a syringe to expose hidden secrets. His work also put forth a radical idea. Where before, inventions such as the lie detector allowed for the scientific measurement of volunteered information, a truth serum suggested that science could actually produce honesty.

Born in New York City on July 23, 1895, William Jefferson Bleckwenn came to the University of Wisconsin in 1913 as an undergraduate. He excelled in track and field, particularly the hammer throw. Graduating in 1917, he enrolled at Columbia University for his MD because the UW did not yet have a four-year medical school. After residencies in psychiatry at Bellevue Hospital in New York City and the UW’s Wisconsin Psychiatric Institute, he became an instructor at the institute in 1922.

At the time, Madison was a center for the study of altered states of mind. In the late 1920s, UW researchers carried out some of the first laboratory studies of hypnotism and investigated cures for neurosyphilis. Charged with leading clinical trials of various drugs, Bleckwenn began experimenting with short-acting synthesized barbiturates, particularly sodium amytal (amobarbital sodium), to treat patients with schizophrenia. Those suffering from rare and particularly debilitating forms of the disease, catatonia and mutism, were often unable to move or speak. Others exhibited just the opposite behavior: excessive motion, pacing, turning in circles, or flailing arms and legs. Looking for a sedative that delivered rest, Bleckwenn was the first to use intravenous barbiturates in clinical practice.

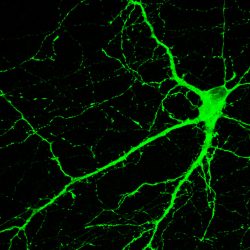

First synthesized by chemist Adolf von Baeyer in 1864, barbiturates are a class of drugs derived from barbituric acid that act as depressants on the central nervous system. Barbiturates such as sodium amytal trigger the brain’s main inhibitory system, which depends on binding between the neurotransmitter GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) and the GABA receptors on the surface of neurons. When these receptors are activated, function slows in parts of the brain. Alcohol, the oldest known drug to loosen tongues, has a similar inhibitory effect on parts of the brain, giving rise to the phrase in vino veritas.

Barbiturates found widespread clinical use as sedatives and anticonvulsants, and they became particularly popular for combatting insomnia in the 1940s and 1950s. They can be extremely addictive and sometimes lethal, however — Marilyn Monroe, Judy Garland, and Jimi Hendrix all died from barbiturate overdoses. Before Bleckwenn, sodium amytal had only limited medical applications as a surgical anesthetic. But its potential for psychic transformation in people suffering from nervous disorders drew the attention of psychiatrists and neurologists.

Bleckwenn induced a deep state of unconsciousness in his catatonic patients — deep enough to remove the strange movements and repetitive actions, and to add the waxy flexibility that allowed patients to be bent into shapes like a human Gumby. As they woke up after many hours of sleep and recovered from the effects of the drug, he found that many of his patients emerged from their catatonic states. They walked and talked. They ate and drank unassisted. They could read and write.

Bleckwenn asked them questions about their paranoid delusions and received answers that he had been unable to coax out of them before. Most of his patients were long-term sufferers of catatonia. Some had been on feeding tubes for years and did not respond to the catharsis or talk therapy developed by Freud. The effects during the period Bleckwenn called the “lucid interval” were usually temporary, but remarkable.

“With ‘Sodium Amytal’ we are now able to pierce the mystery of this obscure mental state and bring them out to a normal mental level for from four to eighteen hours a day,” wrote Bleckwenn in the

Wisconsin Medical Journal. “We are using psychotherapy and other methods during the lucid intervals to produce recoveries and have had excellent results.”

Bleckwenn treated one twenty-year-old UW student who had suddenly become confused and stopped talking and eating. He developed “active hallucinations” and sang and yelled, day and night. Given sodium amytal, the student realized “he was having a terrible time and hoped to recover so as to enter school at the beginning of the next semester,” Bleckwenn wrote. During his lucid interval, the student discussed current events, school, his illness, and his future plans. He lapsed back into a catatonic state as the drug left his system, but daily injections lengthened his lucid periods — so much so that Bleckwenn eventually reported that the student was working for a florist, “perfectly adjusted at present.”

Bleckwenn made a dramatic film from his experiments in 1936, titled Effects of Sodium Amytal Narcosis on Catatonia, that featured footage of patients before and after treatment. One man sits with his head down, his chin resting against his chest. Four hours later, the same man is shown sitting up, writing, drinking, buttering bread, and even smiling shyly at the camera. The film allowed audiences to experience Bleckwenn’s therapeutic work more succintly than a visit to the Wisconsin Psychiatric Institute ever could.

For Bleckwenn, sodium amytal seemed to open a window into the behavior, skills, and personality of his patients before the onset of illness. “The memories expressed under its influence are relived and embodied in the subject,” he explained. With sodium amytal, patients express “a greater willingness to eat and take fluids … They are more active, more talkative, have less constrained and awkward attitudes.” By the mid-1930s, Bleckwenn’s work, along with that of his colleague William Lorenz, had become standard reading on the psychological effects of drugs on psychiatric patients, and sodium amytal had become commonly referred to as “truth serum.”

The idea sparked the imagination of journalists, writers, and dramatists. Police and medical researchers seized on the idea of a technique that could reveal a reality independent of the fantasy life of the individual, a chemical means to tap into the history locked in the brain. And military leaders used the drugs to interrogate enemy soldiers during World War II. During the Korean War, U.S. POWs were subjected to a variety of drug therapies, including sodium amytal, as part of brainwashing efforts.

The substance quickly found its way into the courtroom. In 1931, Bleckwenn injected suspected murderer John Whalen with sodium amytal in connection with the murder of a man in Monticello, Wisconsin. Whalen’s testimony while under the drug led to his release from custody. Bleckwenn, often aided by his colleague Lorenz, administered the drug on several more suspected men over succeeding months and years. Lorenz admitted that the test had limited applicability and was not infallible outside of psychiatric psychoanalysis. “Up to present, we would conclude that the method is satisfactory and successful in the case of innocent people charged with crime,” declared Lorenz in a 1932 article. “In the case of guilty persons, we have not always been successful in obtaining a confession.” Courts generally agreed with Lorenz’s skepticism, despite admitting barbiturate interviews as evidence in some cases.

During the 1940s, sodium amytal was also used on soldiers suffering from shell shock — what we now call post-traumatic stress disorder. Bleckwenn was himself very concerned about the psychological effects of war. Serving in the Pacific as a neurologist and psychiatrist, he had witnessed the horrors of combat firsthand. “Acute emotional breaks occur under combat conditions and are the direct result of fatigue, exhaustion, and the strain in combat,” he wrote. Early treatment was key, he counseled. Under sodium amytal, Bleckwenn believed sufferers would experience the emotional release through telling their stories that would allow them to recover from the trauma of war and resume normal functioning. The drugs could also be used to hunt out fakers trying to shirk their military duty by claiming mental and physical dysfunctions.

Bleckwenn began experimenting with synthesized barbiturates, particularly sodium amytal, to treat patients with schizophrenia. Those suffering from catatonia and mutism were often unable to move or speak. As they woke up after many hours of sleep. … Bleckwenn asked them questions about their paranoid delusions and received answers that he had been unable to coax out of them before. Photo: UW–Madison Archives, S134.

Medical units were given dosages of sodium amytal and a related drug, sodium pentothal, to treat soldiers. At one British hospital, psychiatrists William Sargant and Eliot Slater reportedly gave their patients and staff sodium amytal cocktails to calm fears during the harrowing months of the Blitz in 1940.

The practice continues today. In March 2013, the judge in the Aurora, Colorado, movie-theater shooting ruled that a truth serum could be used on defendant James Holmes should he plead not guilty on the grounds of insanity.

Doubts about the veracity of truth serums have existed from the very beginning: controversy led to rejection and then resurgence time and again. A central issue is the degree of reliability of the memories of the patients and the capricious observations of these memories by witnesses. Films such as the one made by Bleckwenn offered one way to validate evidence and to communicate experiences difficult to put into words.

Even so, while these drugs did make people more willing to talk, later studies found that they were no more likely to tell the truth. Individuals under the influence of barbiturates tend to be extremely suggestible and are more likely to say what the questioner wants to hear rather than the truth. A CIA review of the validity of information gleaned from sodium amytal interviews in the 1950s revealed that many participants recalled false memories. In 1963, Congress ruled that the use of sodium amytal in questioning POWs was torture. Truth serum’s standing has been far more consistent in the popular imagination.

After World War II, Bleckwenn continued to consult on psychiatric care for the military, working with the secretary of war, the surgeon general, and the Veterans Administration to expand the teaching and use of psychiatry. He also resumed his research on narcoanalysis and explored various treatments for chronic pain.

Bleckwenn, the father of truth serum, died of an aortic aneurysm in 1965.

Bleckwenn’s groundbreaking work with sodium amytal set the stage for nearly a century of popular and scientific interest in truth serums. We still don’t have an effective way to extract the truth that works in every instance and on every person. The persistence of myths and theories about lie detecting attest to our as-yet-unrequited desire to expose hidden truths.

Erika Janik MA’04, MA’06 is a historian, author, publisher, and radio producer. Her most recent book is Marketplace of the Marvelous: The Strange Origins of Modern Medicine (Beacon Press).

Published in the Spring 2015 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.