Rules to Roll By

Shana Martin (left) competes against log roller Taylor Duffy at the 2011 Lumberjack World Championships in Hayward, Wisconsin. Duffy defeated Martin in the finals to take top honors this year. Photo: Darlene Prois

With the threat of Huntington’s disease hanging over her, Shana Martin lives life out on a limb – or at least a log.

If you want to take up the ancient and noble sport of log rolling, here are two tips to keep in mind: 1) never look down at your feet.

“The key to log rolling, right away, is eyes on the end of the log,” says Shana (pronounced shawna) Martin ’02, instructor for Madison Log Rolling and three-time world champion in the sport. “You want to be looking off to the right or left. You don’t want to be looking at your feet, because where you look is where you go.”

And 2) keep your feet in motion.

“It’s like stomping ants, that’s what we tell kids,” Martin says. “You’ve got to move your feet as fast as you can up and down, not trying to spin the log or anything else. If you stop your feet, and the log starts to spin, your brain can’t catch on fast enough to keep you up there.”

Martin gives this advice to the log rolling students — aspiring lumberjacks and lumberjills — who gather for lessons on the western shore of Madison’s Lake Wingra on summer afternoons when the weather is fine. She teaches them to climb up, and to stay up, on floating cedar logs — actually retired telephone poles that have been planed into more perfect cylinders to give them a truer roll. The logs the students use are carpeted, to provide slightly better traction and a modicum of padding. Pros, such as Martin, use uncarpeted logs, relying on spiked shoes for grip and taking their lumps.

Eyes on the end; fast feet. It’s good advice, Martin knows, because these two principles are the ones she rolls by, in sport and in life. For the last quarter century, since she was five years old, she’s been in almost constant motion, always aware of what may be waiting not too far in the distance: a 50 percent chance of darkness, pain, and crippling illness.

Martin’s mother, Deborah, was diagnosed with Huntington’s disease twenty-six years ago. An incurable genetic disorder, Huntington’s travels along a dominant gene. If Shana inherited that gene, she will, inevitably, lose control of her muscles, the capacity to communicate, and, ultimately, her life.

“It’s always been a part of my life,” Martin says. “It’s always been in the back of my mind, but it’s never changed how I’ve done anything. Basically you have to live as if you’re never going to get it. And that’s what I’ve done. I’ve just lived my life.”

Eyes on the End

One day in 1985, Shana Martin learned that her life would turn on a penny.

When Shana was five years old, she and her parents drove to the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. Deborah had been acting odd for some time. She would shake or jerk her arms and legs, as though dancing to unheard music. She would become angry with little provocation. Her symptoms mystified her doctors and baffled her family until that trip to Mayo, which brought the devastating — and stunning — diagnosis of Huntington’s.

“My mother was adopted,” Shana says. “We didn’t know her parents. Basically [the doctors] were finally able to determine that it was Huntington’s disease because she was showing enough neurological symptoms by then.”

The Martins returned home to Madison, and Shana’s father, George MS’74, PhD’78, took her to her room and spelled out the situation for her. George was a UW professor of forestry, the instructor for Forest Biometrics — “the class the students hated to have to take,” he says. A lifelong teacher, he explained the situation to Shana in terms a five-year-old could understand.

Deborah was going to get worse — much worse. She would lose the ability to walk, to speak, and to eat. Shana would have to help take care of her mother. And then George took out a penny and flipped it on the bed. These are your odds of getting Huntington’s, he told Shana. Heads, and you’re in the clear; tails, and you’ll be sick like your mother: a 50-50 chance.

“I remember asking him if it’s heads or tails, and he said I can’t tell you,” she says. “He was very honest about it.”

At the time, there was no test to determine whether a child had interited Huntington’s. That test came along in March 1993, when the Huntington’s Disease Gene Collaborative Research Group announced that it had isolated the defective gene, called Huntingtin, a string of repeated DNA located on chromosome 4. But Shana has decided not to be tested.

That response is fairly common, according to Laura Buyan Dent MD’98, a neurologist with the UW’s Movement Disorders Clinic. “It’s a very individual decision,” she says. “At this point, there’s no treatment for [Huntington’s], so some people think, why bother to find out? And for those who do learn they have it, there’s a high rate of suicide within a few years of the initial diagnosis.”

About 30,000 Americans — one in every 10,000 — have developed Huntington’s disease; another 200,000 are the children of parents with Huntington’s, and so are at risk of inheriting it. The condition has a vicious effect on sufferers and their families. It affects several regions of the brain, but most particularly the basal ganglia, an area near the center of the brain that’s associated with motor control and procedural learning. Huntington’s patients lose a large number of cells in the basal ganglia, leading to an inability to control movement. For many years, the disease was called Huntington’s chorea — from the Greek word for dance — due to the way that sufferers appeared to dance uncontrollably.

Development of the disease can be unpredictable, Dent says. The first symptoms to appear are often psychological or cognitive — that is, related to mood or to memory — but the disease’s signal characteristic is that hopeless dance. Over the course of up to twenty years, patients suffer jerking and flailing limbs, until, in the disease’s final stages, they become rigid.

For Deborah Martin, the first signs had been physical and psychological. “She had balance issues, tripping, falling, contortion,” Shana says. “And the psychological was basically anger outbursts. It was almost like bipolar disorder — she’d be really happy, and then very angry.”

Twelve years ago, Deborah lost the ability to swallow, and had a feeding tube inserted. Ten years ago she lost the ability to speak. For the last six years, she’s been completely non-responsive.

Shana and George go to visit her at least once a week, to talk to her, watch a video of one of Shana’s competitions, or watch a movie. “She’s still fully there, totally,” Shana says. “We believe that completely. And that’s very frustrating when that person is there, they just — they definitely can’t express themselves. Imagine being trapped inside your body.”

To help distract Shana from those imaginings, George and Deborah encouraged her to take up sports. The same day that George flipped that penny and told Shana about her odds, he gave her a guidebook for the local YMCA.

“My parents were adamant that I shouldn’t just be a caretaker,” Shana says. “They wanted me to be involved in as many things outside of the home as possible. And they said, ‘Pick whatever [activities] you want.’ And I picked gymnastics and log rolling, swimming and ballet.”

Not all of those sports took. “I told my ballet instructor that ballet was just like gymnastics, only boring,” Shana admits. But physical exertion came to be her refuge from the demands of taking care of her mother. And log rolling helped her find a community of people devoted to a goal that fit Shana’s personality: the pursuit of excellence in a field that most people consider an anachronism.

Martin sprints down a series of connected logs during a boom run event at the 2011 Lumberjack World Championships in Hayward, Wisconsin. Boom-running can be dangerous, as each log is free to spin independently of the others. Photo: Darlene Prois

Rise and Fall

We are, today, about seven years removed from the golden age of lumberjack sports. Their popularity followed a course that is typical of a log roller’s first lesson: getting up isn’t too much trouble, but staying up is nearly impossible. After all, falling off a log is axiomatically easy.

That golden age came courtesy of ESPN. From 2000 to 2005, the cable network tried to build a fad around lumberjack sports with the creation of its Great Outdoor Games.

“It was bigger than the world championships,” Martin says. “That was, like, our big event — we got to be famous for a few years, and be in ESPN magazine. Today, sometimes, ESPN features one or two of our lumberjack athletes, but not to the extent that the Great Outdoor Games did. It was to the point that we were recognized in public.”

Fame and fortune have generally been rare commodities among these athletes.

Log rolling — also called birling, from a Scottish word meaning spinning — has its origins in the activities of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century lumber camps. Logs were moved from forest to lumber mill by river, and so lumberjacks had to be adept at walking across the floating logs.

“We’re athletes who represent things that happened a hundred years ago,” Martin says. “What we’re doing is living history.”

But what she and other professional birlers are also doing is creating an athletic league with its own rules and culture.

In theory, a log rolling match is simple enough: two competitors stand on a floating log and each tries to make the other fall off. They may spin the log, rock it up and down, or splash water at their opponent, but may not touch their opponent and must keep one foot in contact with the log at all times. The birler who wins the best of five rolls wins the match.

Competitive birlers climb the ranks from junior (up to seventeen) to semi-pro to professional (or elite, in the terms of the U.S. Log Rolling Association). And elite log rollers are ranked by how they finish at sanctioned tournaments held throughout the summer at a variety of locations — most in the upper Midwest — that have historical links to the lumber industry: La Crosse, Madison, Onalaska, and Lake Namekagon in Wisconsin; Grand Marais in Minnesota; Kaslo in British Columbia; and the Lumberjack World Championships, held every July since 1960 in Hayward, Wisconsin.

Martin began competing as an amateur log roller at the age of nine.

“I stank at it,” she says of her first attempts to stay upright on wood. “I was absolutely terrible. But I had so much fun, and I made great friends.”

As she worked her way up the amateur and professional ranks of log-rollers, Martin also explored other sports, often working against the grain. As a student at Madison’s Memorial High School, she joined the track team and became its first female to compete at pole-vaulting, a sport she tried out for mainly, she says, “because they told me girls couldn’t do it.” The decision helped create new opportunities for her.

“Just my luck, my first year at UW–Madison, the Big Ten opened up pole-vaulting for women,” she says. “It was kind of cool. I held all the records at the UW, because I was the first one.”

She became a scholarship athlete in her sophomore year, but even then continued as a professional lumberjill — a situation that would complicate her status as a Badger athlete.

“This was back in the days of the Shoe Box scandal,” she says. In 2001, more than 100 UW athletes violated NCAA rules by accepting benefits from the Shoe Box footwear store in Black Earth, Wisconsin, earning the university a $150,000 fine and probation. The fallout made the university nervous about any scholarship athlete receiving income from an outside source, and Martin had to convince the athletic department that birling wouldn’t create additional complications with the NCAA.

At the time, the money to be made in log rolling was just beginning to rise, though Martin wasn’t yet a top earner. ESPN’s Great Outdoor Games was flourishing, and athletes could win as much as $10,000 with a first-place finish. But Martin was still climbing the ranks. It wasn’t until 2004, after her Badger days were over, that she won her only Great Outdoor Games gold medal, taking top honors in the mixed-doubles boom run.

Like birling, boom-running is also based on floating logs. Competitors race each other in a sprint from one end of a boom — a series of six to twelve logs, linked end to end so that they each spin independently — to another and back again. The fastest time wins the race. Runners may fall (and often do) once or even twice and remount to continue the race, but three falls leads to disqualification.

“It’s quite a different event than just sprinting,” Martin says, “because the logs are moving and spinning, and you’ve got to balance, and people are falling in. It’s a lot more dangerous than log rolling.”

Martin’s gold in the 2004 Great Outdoors Games boom run capped a banner year for her and for lumberjack sports in general. That year’s games were held in Madison, and so Martin took her prize before a hometown crowd. The games in general attracted some 70,000 spectators to attend the events live, and 22 million viewers watched them on television.

But this was the peak of the Great Outdoor Games’ popularity — and their fall wasn’t far off. ESPN and Madison squabbled over money, and the network decided to take its show to Orlando, Florida, for 2005. Low attendance — hampered by the threat of Hurricane Dennis — made that year’s games a failure. In 2006, ESPN canceled the event altogether.

Five years later, the popularity of lumberjack sports has drifted back to historical norms. The legends of the sport — J.R. Salzman, who lost an arm in Iraq, or the Hoeschler sisters, whose sibling rivalry gives an edge to their sense of competition — are no longer public celebrities. But as the sport declined, Martin’s standing in it rose. She won the world championship in log rolling in 2006, 2007, and 2008; in boom-running, she won championships in 2008 and 2009. She narrowly lost the log rolling championship in 2010, to Lizzie Hoeschler (“my nemesis,” Martin calls her).

With the chance for fame and fortune waning, birling did not attract large numbers of athletes. Today, Martin is the president of the U.S. Log Rolling Association, and she says that there are currently about a hundred professional birlers, among about a thousand pro lumberjack athletes. Prizes, even at the highest levels, are hardly enough to make anyone rich. The top birler at the 2011 Lumberjack World Championships took home $1,425. Martin, who finished second for the second year in a row, received $1,000.

“Sponsorships are hard to come by,” Martin says. “For the really small tournaments, first place might be like a hundred bucks — basically, to cover travel.”

As one of the top athletes in her sport, Martin has managed to land sponsors from time to time — the Duluth Trading Company, Lumberjack’s Restaurant chain, Lululemon activewear, even a company called GoGirl. “It’s a feminine urination device,” Martin says. “I actually used it while climbing Mt. Kilimanjaro. It was quite the lifesaver.”

But she also sees that her time at the top of her game is limited, and she’s trying to prepare for life after she’s fallen from her last log. “This is a young-woman’s sport,” she says.

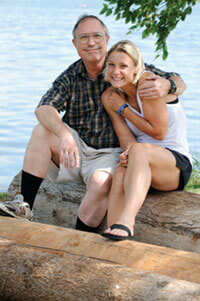

Shana Martin and her father, George, sit on logs that George has just delivered to Madison’s Lake Wingra. Though George is a former forestry professor, Shana says his academic interests did not push her toward log rolling as a sport. Photo: Jeff Miller

Fast Feet

If Huntington’s disease is going to catch up with Shana Martin, it will have to move fast, because she seldom slows down. She can’t afford to. The disease’s typical age of onset is between 35 and 45. Martin is 31.

In any given week, she might be submitting herself for testing by Huntington’s disease researchers, or meeting with the Huntington’s Disease Society of America, or speaking on its behalf to a Kiwanis Club or an Elks Lodge or a YMCA.

“The way I cope is by speaking,” she says. “Some people pull in. Some are in denial. I started to get involved when I was sixteen years old.”

In fact, her involvement goes back several years earlier, to when her mother’s deterioration was a cause of ostracism in the harsh social world of elementary school. Martin’s classmates were often confused by her mother’s odd behavior or terrified by the thought that they might catch whatever it was Deborah had. Shana was the weird kid with the weird mom. “I had a pretty rough childhood,” she says. “I got picked on a lot.”

But in sixth grade, Martin’s teacher at Madison’s Jefferson Middle School asked her to give a speech on any topic of her choosing. Martin chose to explain Huntington’s to her classmates: her first experience in using communication as a coping mechanism.

“I remember being so scared I cried beforehand, and before the speech, I even asked the kids — I begged them — I said please don’t make fun of me,” Martin says. “I stood in front of these kids, and I gave this talk about my mom’s life. And my whole world turned around. All those kids who used to make fun of me, they just asked questions for the rest of the school day. None of them really understood until I gave that speech, and that’s when it dawned on me how important it was for people to learn what this mysterious disease is.”

But speaking is just a small part of Martin’s life — and hardly remunerative. Like most professional log rollers, she can’t make a living solely from the prizes won at tournaments. Some lumberjack athletes supplement that income by performing at shows — exhibitions at which athletes show off their timber talents while talking about lumberjack history and entertaining spectators with mock competitions and physical comedy.

“Shows are cheesy,” she says. “You wear flannel, have bad jokes, and all that. A lot of log rolling competitors do them for a living. They travel to different fairs and do demonstrations. Every so often they’ll call me up and say, ‘Hey, we need a log roller for a show,’ and I’ll go and do it, but I don’t do shows for a living.”

Instead, Martin keeps a day job as the fitness director at Madison’s Supreme Health and Fitness, a career she says had been in her plans since she was a teen. A kinesiology major at the UW, she has always pursued exercise and education. She’s coached track at Wesleyan University in New England, and she’s “lived the dream of a Beverly Hills personal trainer,” in her words. But her eyes were always back on Madison.

“It’s been my main job, my home base, my passion since I was in high school,” she says. “When I lived in Connecticut, when I lived in L.A., I knew I was going to come back when a fitness director position opened up. I don’t make a lot of money, but it’s [like] family there.”

Martin supplements her income by traveling to certify other fitness professionals for a company called TRX, which created a suspension training system — a set of nylon straps that act as a sort of portable gymnasium. The variety and physical intensity of her engagements keep her almost constantly on the road.

“A lot of people say I wanted to be physically active because it will help take care of my body, that it will put off the onset of Huntington’s disease,” Martin says. “That’s one possibility, but I actually don’t think that. My parents got me physically active at a young age, and I loved it. I loved everything about it. I saw how much fun everybody had, at every ability level, and knew this is what I wanted to do.”

But as she promotes lumberjack sports or fitness or support for Huntington’s patients and research, she does so with the understanding that her life could change drastically tomorrow.

Shana Martin sits with her mother, Deborah. A victim of Huntington’s disease, Deborah has been on a feeding tube for twelve years and non-responsive for the last six. Shana and her father, George, visit Deborah every week. Courtesy of Shana Martin.

“I’m adamant about not learning whether [I have the gene],” Martin says. “If I found out I had it — or that I didn’t — I don’t know how my life would change. Basically, you have to prepare as if you’re going to get [Huntington’s], but live as if you’re never going to get it.”

John Allen is not only senior editor of On Wisconsin Magazine; he’s also the publication’s most experienced log roller.

Published in the Winter 2011 issue

Comments

Andre Boutin November 21, 2011

Touching… Very similar story to mine as I was also adopted and never met my father and never knew about the disease. Like Shana, I had a lot of success in my career and won numerous prizes. In my late forties, I had strange sensations in the thigh and minor twitches around the eyebrows. It is only when my daughter asked to find my father, and after seeing him that I understood. He had HD, like his mother, many of his sibling, many of his daughters. Now my disease is progressing, memory, depression, social withdrawal, … I wish I had never found him.

wes johnston November 23, 2011

Shana’s story and dedication to finding a cure or effective treatment for HD is treasured within the HD community. Shana has used and is using her athletic achievements to increase awareness about HD and produced venues for contribution to HD research. She is a great young lady and I am privileged to know her.

Wes Johnston

Board of Directors

HDSA Northeast Ohio Chapter

Jack Murray November 29, 2011

I was extremely gratified to see this wonderful article about Shana Martin in On Wisconsin, and immediately put it up on my Facebook page for all of my friends and fellow Badgers to see. Shana is a true inspiration.

HD runs in my family, and I know too well how easily, and thoroughly, it can devastate decimate a family and decimate family resources. The decision of whether or not to be tested, and how to handle the stress of HD in the family and even the possibility of having HD, is especially trying for young people, who all too often keep the secret of HD in the family to themselves.

Shana, and On Wisconsin, have done a great service to Badger students and the public at large by publishing this great story.

Every time an article like this gets published, it helps to break down the walls of isolation for families at risk, reduces the ignorance and fear of others, and helps to speed the day when we will find the urgently needed treatments and a cure.

As a former Research Administrator for the National Headquarters of HDSA, (and a longtime reader of On Wisconsin) I recall that in years past there were scientists at UW-Madison engaged in research on HD–in fact I recall reading an item blurb about this some years ago in On Wisconsin. A great follow-up to this article would be to get more information on their important contributions.

Jack Murray

Jersey City, New Jersey

L&S ’90

Zach Heise July 13, 2012

I purchased the Madison Log Rolling groupon because I read this article a few months ago. About to have my 2nd lesson this afternoon! Shana is a great instructor – very funny and upbeat.