Greyson’s Anatomy

Shana Martin Verstegen has a new life without the threat of Huntington's disease.

Clap. Clap-clap. A toothless grin splits Greyson’s large, round face, and the seven-month-old looks around the room in search of applause for his latest accomplishment: applauding.

His eyes fix on me — we share a common hairline, and perhaps he thinks that makes us simpatico. I smile and nod.

He turns to his mother.

“Look at him go,” says Shana Martin Verstegen ’02. “He just clapped for the first time yesterday. Who’s a happy boy? Who’s a happy boy?”

Grey is, obviously, a very happy boy, but in that he isn’t unusual. His mother’s beaming pride, the living room cluttered with toys, a car seat, an Exersaucer, and all the paraphernalia that accrue around a modern infant — this could be the environment of any middle-class, Midwestern American baby.

What makes Grey different is that his clapping might never have been heard — not by me, not by Shana, not by anyone. A year before I visited him, there was a 50 percent chance that Grey would never be. Five and a half years earlier, when I first met Shana, those odds were even lower.

In 2011, I wrote a profile of Shana for On Wisconsin Magazine called “Rules to Roll By.” Shana was then a world-class lumberjack athlete — she had competed in the log-rolling and boom-running championships in Hayward, Wisconsin, and won several times. She was also a speaker and advocate on behalf of the victims of Huntington’s Chorea and their families. Huntington’s is a genetic disease — it’s degenerative and incurable. It kills more than 90 percent of the people who carry the Huntington’s gene. Most of the rest commit suicide.

Shana’s mother, Deborah Martin, had Huntington’s, and so Shana knew she had a fifty-fifty chance that she had the gene. She didn’t want to bring a child into the world who would watch a mother suffer the way Deborah had or bear a child who might develop the disease.

But many things have changed in the last five years. And one of them is Grey.

5 out of 100,000 Americans have the Huntington’s gene, studies estimate

Deborah

Huntington’s is a particularly cruel genetic disease in a couple of respects. First, it runs along a dominant gene, the IT15 (“interesting transcript” 15) gene. There are no recessive carriers. If you have the Huntington’s gene, you will have the disease, and if you have children, there’s a 50 percent chance that they’ll develop it, too.

Second, those who have Huntington’s don’t exhibit signs until they’re in their thirties, typically in the later child-bearing years.

Huntington’s is a neurodegenerative disease. Patients usually first show problems with mood and cognition, then coordination. They develop a shuffling gait and jerky body movements, and ultimately they lose all ability to move or communicate. Deborah Martin first learned she had the disease in 1986, when Shana was five years old. Deborah had been adopted, and she never knew her birth parents. She had no idea that one of them had Huntington’s and that she might, too.

But from that day, Shana knew that her life rested on the flip of a coin: heads, she didn’t have the gene and would likely live a long life; tails, she had the gene and like her mother, would enter an unstoppable decline shortly after reaching adulthood.

The Huntington’s gene was discovered in 1993, and scientists soon developed a test for it. But as there’s no cure, or really much in the way of treatment, Shana had been determined not to take the test.

“I’m adamant about not learning whether [I have the gene],” Shana told me in 2011. “If I found out I had it — or that I didn’t — I don’t know how my life would change. Basically, you have to prepare as if you’re going to get [Huntington’s], but live as if you’re never going to get it.”

So Shana threw herself into her career as a log-roller, and she became a spokesperson in the Huntington’s community. But in spite of her adamant position, she knew even then that there were situations that would motivate her to take the test: if she was tempted to marry or have children. If she married, she wanted her husband to be prepared for what might happen to her, as her father, George Martin MS’74, PhD’78, hadn’t been. And she didn’t want to have a child if there was any risk of perpetuating the disease.

And that’s where Peter Verstegen enters the picture. Peter and Shana had known each other since high school. He knew Deborah, and so he knew the risks. They didn’t deter him.

“[Huntington’s] didn’t scare me,” he says. “Not really. That’s not who Shana is.”

Shana Martin Verstegen holds a photo of her mother, Deborah Martin, long before she showed signs of Huntington’s. Deborah passed away in 2014.

He proposed in March 2013, and Shana accepted. They told her mother, and according to Shana, Deborah made eye contact for the first time in years. “We took that as her knowing I was going to be okay,” Shana says.

Two weeks later, Deborah passed away.

Shana and Peter celebrated Deborah’s life. They celebrated their engagement. And, later, in November, they celebrated their marriage. Then the couple began to think about babies.

“There are really three ways you can go about having children if you’re at risk for Huntington’s,” Shana says. “You can cross your fingers and hope for the best. I didn’t want to do that. You can have in vitro fertilization, so that doctors test your eggs and only implant ones that don’t have the gene. But that’s really expensive. Or you can take the test yourself. I didn’t love it, but that’s the route we chose.”

Clumsy

When I first met Shana, she was thirty and had been living with the fear of Huntington’s for five-sixths of her life. She was trying to live like she was never going to get Huntington’s, but while the sentiment was brave, it wasn’t always practical. The shadow of the disease was never far from her.

“Every time I had a clumsy day,” she says, “every time I cut myself or stumbled or couldn’t think of the word I was looking for, I wondered: ‘Is this the first sign?’ ”

But if wondering about Huntington’s was stressful, actually facing the test was terrifying. And expensive. And lengthy. She would have to see a genetic counselor, who would judge whether she was emotionally ready for the test. Before the Affordable Care Act came along, Shana says, a positive test “would have been health insurance suicide.”

In February 2014, Shana applied to her insurance to pay for the test. In March, she began meeting with Jody Haun ’75, MS’85, a counselor with the UW Waisman Center’s Medical Genetics Clinic. They talked about what would happen if the test was positive: if she had the gene. They talked — considerably less — about what would happen if the test was negative. “It was very scary,” Shana says — not the meetings themselves, but merely deciding to confront this question with finality.

Eventually, in March, the clinic drew her blood and sent it off to a lab, which examined Shana’s fourth chromosome for evidence of IT15. In a section of that chromosome, cytosine, adenine, and guanine are repeated many times. Normal genes have twenty-six or fewer repeats; the Huntington’s gene has forty or more.

But Shana could do nothing but wait, “so I kind of put it away in my mind and didn’t think about it,” she says.

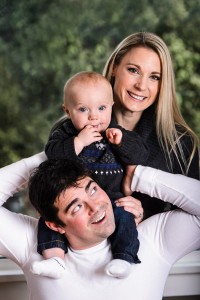

Shana didn’t inherit the Huntington’s gene, and so neither will her son, Greyson, shown here with Shana and her husband, Peter Verstegen.

Or at least she tried, until the news arrived. On Tuesday, June 24, 2014, Shana returned to Haun’s office to get the results.

“I came in, and she had tears in her eyes,” Shana says. Her heart dropped. But the tears were joy rather than sorrow — after two decades of watching her mother die, of wondering daily if she was doomed to the same fate, Shana found that her burden was gone. She didn’t have the gene. For her, Huntington’s had died with her mother and would never affect her or any children she might have.

That night, she told her father. George said he had been certain her results would show no Huntington’s. “He said he knew,” Shana says. “He said I was too old, that I hadn’t shown any signs. But I could tell he was relieved.”

The next day, she shared the news with the rest of her family, her friends, and the Huntington’s Disease Society of America.

Eleven months later, on May 23, 2015, Greyson Verstegen was born.

“I’m still working for the same purpose. We still need to support research; we still need to find a cure for this.”

— Shana Martin Verstegen

On a Roll

When Shana thought she might develop Huntington’s, she tried to live as though she’d never get it. Now that she knows she won’t, she tries to maintain the same gratitude for every moment.

She continues to work with the Huntington’s Disease Society of America, making speeches and raising money for research. “I have some survivor’s guilt,” she says. “Many friends, people I’ve known for so long, will get the disease. But I won’t. That’s really tough. But they’re also my biggest cheer group. And I’m still working for the same purpose. We still need to support research; we still need to find a cure for this.”

When clumsy days come, she still has a moment of doubt. “It still hits me,” she says. “I’ll start to think is this — and then remember that it isn’t. I can’t help smiling.”

And she continues to pursue her career and her sport. In 2010, she had just lost the title she’d held for two years and was scheming to get it back, and in 2012, she won the women’s world log-rolling championship.

A month after Grey was born, Shana was in Hayward, competing at the 2015 Lumberjack Games.

“I didn’t do well,” she says. “I fell in the standings a lot last year.”

But she’ll be back again in June, hoping to regain her title. She’s now thirty-six, and if she wins this year, she’ll be the oldest woman ever to be a log- rolling world champion.

And if so, then clap-clap-clap: Grey will get to show everyone his latest talent.

John Allen is senior editor of On Wisconsin.

Published in the Summer 2016 issue

Comments

Patricia Wolf May 17, 2024

I will never ever forget you and how friendly and loving you are. It breaks my heart that my 2 boys had to grow up feeling the way you felt, knowing they could get this blasted disease. One of my sons DID get the gene, and all I want to do is make it disappear. My stepson has the disease from his Mom, and my husband and I took care of her for several years, before she had to go into a nursing home. I pray that my husbands daughter and our 18 year old grandson is able to escape this life sentence. We have lost many dear friends because of this disease and also very many brave caregivers who have now become beloved family members. Thank you for writing this, it will truly help people understand what our children live with not knowing what their future may be. My children’s father and I never even heard of this disease and if it wasn’t for a sharp eyed nurse when my father in law had hip surgery, who reported to a movement Doctor that she felt he may have an undiagnosed neurological disease, that we found out. My ex passed away several years later.