Defending a 9/11 Suspect

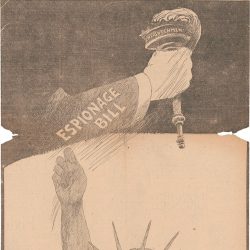

Attorney Edwin Perry sticks up for constitutional principles.

Defense attorney Edwin Perry ’97 understands that most Americans don’t sympathize with the five men who are facing trial, and potentially the death penalty, for allegedly plotting the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001.

“But as Americans, not only should we be concerned about bringing terrorists to justice, we should be concerned about what our government does in order to effect that justice. We have to decide what kind of republic we want to have,” says Perry, who represents one of the accused.

The trial is scheduled for January 2021. It has been delayed for many reasons: The suspects were held by the U.S. government in detention for years before being charged or given attorneys; the Obama administration tried to get the case moved from a military court to a standard civilian court; and, since being arraigned in 2012, the defendants have been the subject of dozens of complicated pretrial hearings.

Perry worked for 12 years as a federal public defender in Memphis, Tennessee, before being hired in 2015 as one of the civilian attorneys representing Walid bin Attash. Attash is one of the men charged as a coconspirator with Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, who is accused of orchestrating the attacks that killed nearly 3,000 people in New York, Washington, and Pennsylvania.

The five men were captured in Pakistan in 2002 and 2003. According to lawyers, they were held incommunicado in CIA prisons and subject to waterboarding, sleep deprivation, and other ill treatment before being delivered to the detention center at Cuba’s Naval Station in Guantánamo Bay in 2006.

The trial will take place in front of a military judge and a jury chosen from military officers at Guantánamo Bay.

“If a federal judge determined that the government had tortured the defendant for about three years and then decided to charge him eventually with a crime, I think a federal judge would likely dismiss the charges — or, at a minimum, suppress any statements made by that defendant,” says Perry. It still hasn’t been determined how much information gathered through torture will be allowed at the trial. “But that’s very much an open question in military commissions, which makes it a court of dubious constitutional foundation,” he says.

The bottom line is that the trial, in Perry’s view, will not be what most Americans would expect.

Published in the Spring 2020 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.