Project Pawpaw

A biologist hopes to make a highly beneficial fruit more widely available.

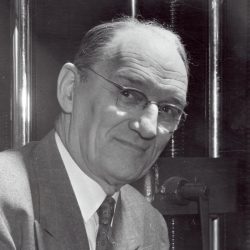

For Adam D’Angelo, encountering the mysterious pawpaw tree sparked a lifelong passion for plant breeding. Courtesy of Project Pawpaw

Adam D’Angelo MS’23 was 10 years old when his older brother took him to visit a research orchard at Cornell University and pointed out a tree with long, teardrop-shaped leaves: Asimina triloba, commonly called the pawpaw, which produces North America’s biggest native fruit.

The younger D’Angelo was confused. “But I know all the fruits,” he insisted. Like most people, he’d never seen, much less tasted, a pawpaw. The roughly palm-sized green ovals are characterized by creamy, yellow-orange flesh. In the wild, the flavor of pawpaws ranges widely, from a blend of mango and banana to marshmallow or even vanilla ice cream.

For D’Angelo, encountering that first, mysterious pawpaw tree sparked what would become a lifelong passion for plant breeding. After completing an undergraduate degree in plant biology at Rutgers, he joined the lab of UW–Madison plant and agroecosystems professor Irwin Goldman as a graduate researcher. D’Angelo worked on crops such as the Badger Flame beet, which bred sweet, colorful vegetables mild enough to eat raw.

“The best advice I got from Irwin is that people eat with their eyes,” D’Angelo says. “Food is such a human experience, and people are drawn to the inherent beauty of plants. So if you can emphasize that, it really helps with people’s willingness to try something new.”

Now, D’Angelo has launched Project Pawpaw, an ambitious effort to breed commercial pawpaw trees to produce more consistent and appealing fruit with a longer shelf life. Wild pawpaw fruit has an especially brief season and goes bad quickly, which makes it impossible to transport long distances and keep in grocery stores. “If we can fix the shelf-life issue and a few other small [plant-breeding] issues, we could have a product that can be grown locally, provide economic viability to small farmers, and provide community members with access to high-quality, delicious fruit,” D’Angelo says.

D’Angelo is preparing to plant 1,500 pawpaw trees this spring at a research orchard in southern New Jersey that he’s been carefully tending and preparing for several years. “We’re really only one or two steps away from having a great fruit crop for North America,” he says. “Pawpaws can be grown using fewer pesticides or fertilizers than conventional fruit crops. They are adapted for life in this climate, meaning we can grow tropical-tasting fruit right here, instead of shipping it from across the world.”

Project Pawpaw is funded by sales of pawpaw-themed merchandise and tree seedlings. D’Angelo also offers reliable, science-backed resources to novice pawpaw home-growers. To learn more, visit projectpawpaw.com.

Published in the Summer 2024 issue

Comments

Cécile Stelzer-Johnson August 28, 2024

In Central Wisconsin, zone 5, we don’t even have them in stores, but if they don’t travel well, this explains that.

I would love to try and plant a couple but I live in deep sand and we were just pushed from zone 4b to zone 5.

Do you know anyone who sells young trees in Wisconsin?

Eugene Hersey October 7, 2024

I am harvesting our first crop of Pawpaws grown in the Central Sands area of WI. They are very sweet and delicious! It took around 8 years before they fruited.