Paradise on Mendota

For half a century, idyllic Camp Gallistella served as a makeshift tent colony for UW summer-school students.

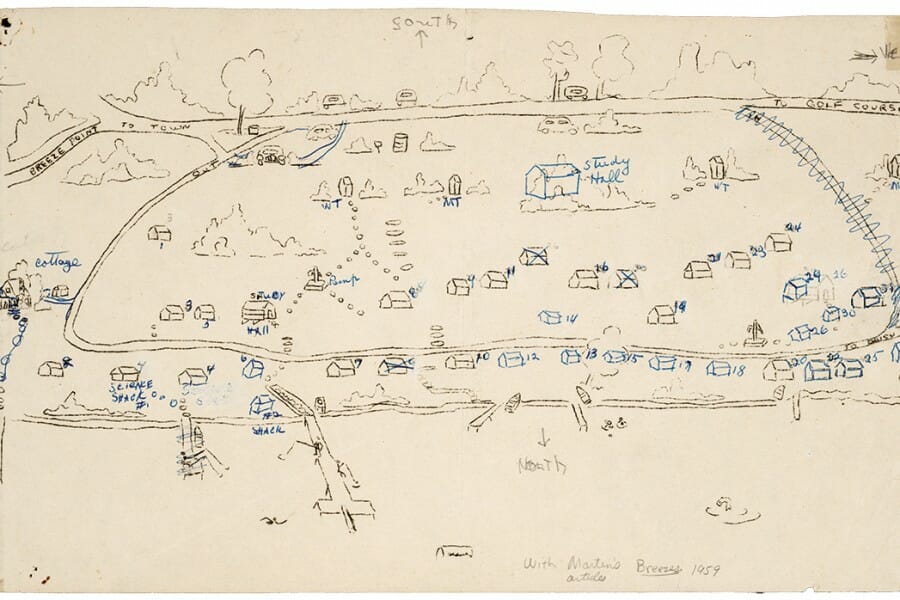

IIn 1911, the University of Wisconsin purchased wooded shoreline on Lake Mendota, just west of Picnic Point, below a hill called Eagle Heights. Many thought the asking price — $1,100 per acre — was as steep as the landscape and wondered what the university would do with the land. But a year later, a group of College of Agriculture students asked the dean of the UW’s summer school if they could camp on the property while classes were in session. It wasn’t long before a 25-acre tent colony on the lakeshore was a cherished tradition, known as Camp Gallistella.

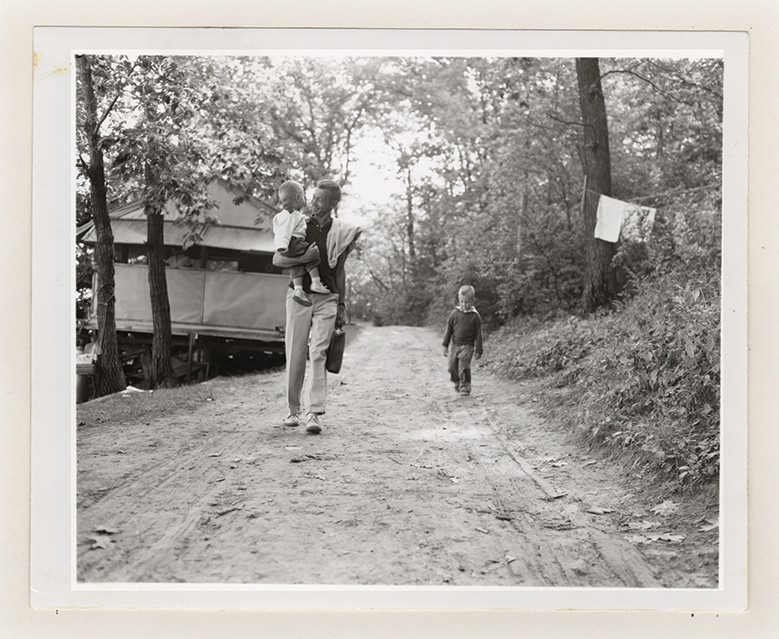

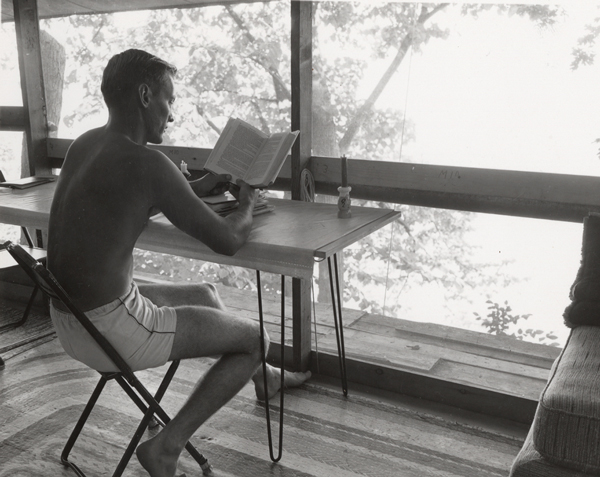

The cost of living was cheap and the recreation plentiful. For the next 50 years, hundreds of students, some bringing spouses and children, pitched tents and spent the summer months boating, fishing, swimming, picnicking, and, of course, studying. Each morning, the commuting students made the two-mile trip to campus by foot, rowboat, canoe, or car. Those who traveled by water would dock near campus and climb Bascom Hill to attend lectures, leaving behind the whiff of pancakes on the griddle and the sounds of their waking families about to spend the day on the lake.

Remnants of Camp Gallistella are still visible near Lake Mendota, confirming that this idyllic colony really did exist on campus. It was a domain of tar-paper dwellings, afternoon teas, and communal governance — a low-rent paradise that, ultimately, wasn’t sustainable beyond the early 1960s.

Tar-Paper Town

Camp Gallistella got its moniker from the couple who served as supervisors for most of the tent colony’s existence. Albert Gallistel was superintendent of the UW’s buildings and grounds department. Beginning in 1919, he and his wife, Eleanor, spent each summer at a small cottage on the eastern edge of the camp property, presiding over the colony from its yearly setup to the fall breakdown.

Beginning in the early 1930s, the Gallistels had phone service installed at their cottage. Eleanor took messages for campers and deputized a couple of older boys in the colony to deliver them three times a day. She sorted and delivered the mail, which, in the earliest years of the camp, arrived daily by boat. She also cultivated a large garden — including a surfeit of daylilies — and made sure tent flaps were closed when summer storms rolled in off the lake.

Initially, there were 18 wooden tent platforms in the woods. As demand for accommodations grew in the 1920s, two dozen more platforms went up along the shoreline. Twenty-six more sprung up on the hillside in the 1930s.

Summer rental began at $15 in the 1920s, rising as high as $35 in 1960. Most families erected light, wood-framed shelters covered with tar paper on top of the platforms, and then fashioned a roof using canvas rented from the John Gallagher Tent and Awning Company, which still operates in Madison. There was not much interest in creating curb appeal.

A thunderstorm would occasionally wreak havoc on the colony’s slapped-together structures. David Cross ’76, who stayed at the camp for five summers as a boy, remembers a storm waking him up in the middle of the night. The family climbed up the hill, huddling together beneath a poncho, to seek shelter in their station wagon.

Summer-school students, some bringing spouses and children, pitched their tents at Camp Gallistella and spent their days boating, swimming, fishing, and picnicking. UW Archives

The camp provided two screened and lighted study halls for students to get homework done in relative peace and quiet. Before electricity was installed in the late 1920s, Eleanor kept the study hall lamps filled with oil. Kids were told to keep the noise down near the study tent, says Cross, but he also remembers hearing laughter coming from card games inside.

Campers were generally high school teachers, school superintendents, and university professors looking for affordable housing while they took summer courses. Given the typical requirements for advanced degrees, return visits were frequent. The record be-longs to Stephen Stover MS’55, PhD’60 and his family (four daughters and one son), who spent 10 summers at the camp away from their Milwaukee home. Stover earned his PhD in geography, and then his wife, Enid Harcleroad, began graduate studies.

“The Wonders of Camp”

The camp opened with the university’s summer session in early July. The residents governed themselves like a town, and the first order of business every year was to hold a meeting to elect a mayor and various town officials. Few escaped some form of responsibility. There were posts for a clerk, a treasurer, a constable, a street commissioner, an athletics director, an editor for the camp newsletter (Gallistella Breezes), a conservation commissioner, a postmaster, aldermen, and census takers.

The Breezes read like a small-town gazette, with notes about “out-of-towners” visiting the colony, congratulations to campers earning degrees, and brief reports on camp activities, including afternoon teas. “Van Lee and Ellen Amt were voted the wonders of camp as they produced homemade cookies and brownies for refreshments,” editor Mildred Olsen reported in 1952. “Mrs. Gallistel arranged a beautiful tea table using wild columbine foliage on a lace cloth.”

Up until World War II, as many as 300 people — including students, spouses, and children — lived in the colony. Population dipped during the war, but by the late 1940s and through the 1950s, its numbers bounced back close to previous levels. While the greatest number of campers were from Wisconsin, attendees came from every corner of the country.

David Cross’s parents shepherded five children through the camp between 1957 and 1962 as David’s father, Bob Cross MS’61, a high school teacher from West Bend, Wisconsin, earned his degree. At the height of the baby boom, the camp was crawling with little kids, and diaper-service trucks were a common sight. “This was long before anyone had ever thought of disposable diapers,” Cross says.

Loud Shouts Forbidden

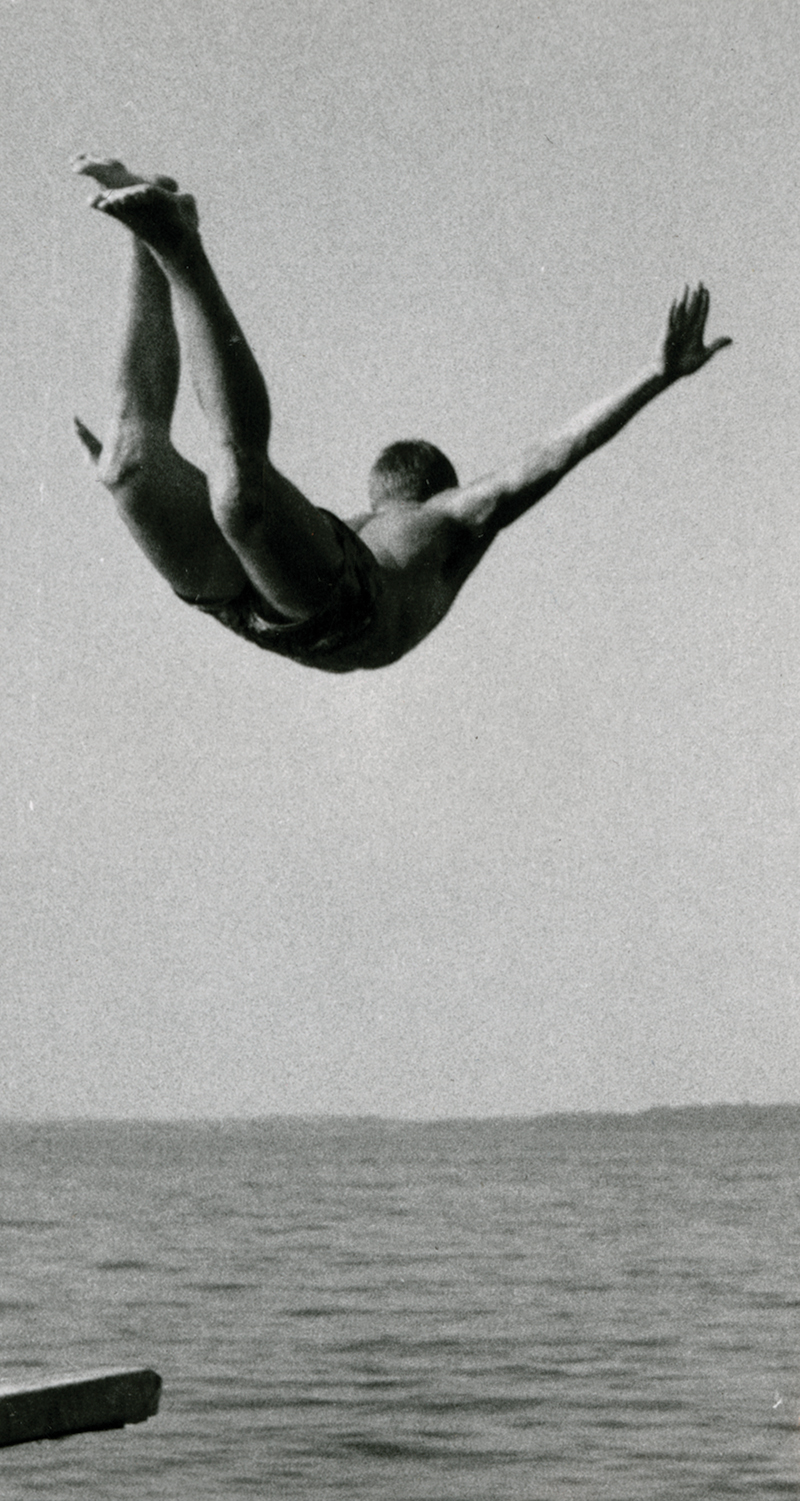

Kids swam, fished, and took rowboats out onto the lake all day long. Adult and youth baseball leagues played on fields up the hill from the camp.

Piers on the tent colony’s property accommodated swimmers and boaters. One year, the Gallistels penciled in a curious amendment on the sheet of camp guidelines: “Loud shouts — especially ‘Help!’ — by swimmers or boaters is [sic] forbidden.”

The camp’s Friday fish fry was popular, and campers could catch walleye, northern, and bass in the deeper parts of Lake Mendota if they were lucky. But the most common fish was perch, often caught in a busy, migrating “perch patch” easily identified by the cluster of boats that surrounded it.

Fish fries would follow a big catch, with families shuffling around potluck tables loaded with hot dishes, salads, and pitchers of Kool-Aid. Lawn chairs were reserved for the cooks, while the victorious anglers occupied stumps and balanced paper plates between their knees while sipping 3.2 beer, the only alcoholic beverage allowed in the camp.

The Water Carnival was an annual highlight for campers. A report on the 1952 carnival describes a parade of children marching loudly to the pier. The Gallistels climbed into a boat and presided over events from the water for a better vantage point. There followed a series of kids’ swim races in small fry, carp, and shark categories; “dead man’s and woman’s float” contests; an inner-tube race for couples; a tug-of-war; and rowboat races. There was also a “watermelon scramble,” which featured a greased watermelon floating free in the lake while teams frantically tried to capture it. “It looked dangerous,” says Cross, “and only adults entered.”

The Water Carnival was known to crown a queen. Showing an egalitarian streak, parents debated whether it was a good idea to single out one of the camp daughters for this high honor.

Paradise Lost

The university decided to close the camp following the summer of 1962, three years after the Gallistels retired. Its population had shrunk to just 17 families, which made running the colony more expensive. The tent platforms and study halls were in need of costly repairs.

There was also a sewage problem. In response to a letter from a former colony member who wondered why the UW had to close the camp, President Fred Harrington explained that runoff into Lake Mendota was increasingly a problem. Creating a new sanitary disposal system for the tent colony would be a major expense, since the sewage would have to be pumped uphill to connect with the Eagle Heights system.

Eagle Heights, the new graduate-school housing under construction up the hill from the camp, would quickly prove more popular than a tent lifestyle, if not quite so affordable. The apartments still house graduate students and their families today.

Remnants of Camp Gallistella dot the lakeshore path, which runs through the acreage still known as Tent Colony Woods. Today this is just a portion of the 300-acre Lakeshore Nature Preserve, an outdoor teaching and research laboratory along the shores of Lake Mendota.

Concrete abutments coursed with iron rods show where the swimming pier stood. Cement blocks cover what was once a camp well, and the women’s latrine is survived by a cement foundation. Scattered moss-covered blocks mark the remains of a tent platform or two.

And on the eastern edge of the woods, a large patch of daylilies still pops up every spring, right where Eleanor Gallistel first planted them.

Tim Brady ’79 is a freelance writer based in Saint Paul, Minnesota.

Published in the Summer 2020 issue

Comments

Terin Miller July 25, 2025

Excellent article – thanks for rerunning it – I have never read before. I grew up in Shorewood Hills in the 1960s, with elementary school friends who lived in Eagle Heights (we’d meet at the ‘fire lane’ for Eagle Heights which opened onto Oxford Road), and have never known of this camp’s existence.

My understanding is that my father, who first came to the UW-Madison to teach Anthropology in 1960, and mother (who taught Anthropology for the UW-Extension and also taught at Beloit College), rented/lived in a trailer maybe near ‘Castle Rock’ for the first year, moving into the house I grew up in on Sweetbriar Road in 1961-62.

I suppose, as he wasn’t studying or working on an advanced degree, we probably weren’t eligible for the Tent Camp. Though I certainly spent much of my childhood swimming and exporing the woods around Picnic Point and what later became the intramural fields/nature preserve along University Bay Drive, I never even had an inkling.

By the time I and my friends were doing that, it was a few years after the camp closed, but I’m surprised I never came across ‘artifacts.’

Anyway, many thanks for the informative, well-researched historic article!