Humanities for the Real World

Kathleen Lewis ’11 created Cover Your Mouth!, above, a digital illustration, while a student, hoping to reach all age groups and inspire better hygiene. Across the campus, students are exploring smart media — formats that incorporate images, text, sound, and data to express ideas. Humanities disciplines are now embracing the digital age — and it’s a natural fit. “Humanists are all about rhetoric, storytelling, creativity,” says Jon McKenzie, a UW English professor who directs the UW’s DesignLab, a center that works with students and faculty who are delving into smart media. Other digital projects created by students (most now alumni) are shown on the following pages. Courtesy of UW DesignLab.

Across the campus, a new energy is reshaping these disciplines and embracing the very technology that could have endangered them.

Does history really matter?

Is an English major irrelevant?

Should philosophy be phased out?

Are the humanities going extinct?

Far-fetched questions? Don’t be so sure. An alarming report, commissioned by members of Congress and released to the public last year by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, argued that support for the humanities — English, history, philosophy, the languages — is eroding in families, schools, government, and the job market.

“Economic anxiety is driving the public toward a narrow concept of education focused on short-term payoffs,” warned the authors of “The Heart of the Matter,” a report whose findings made headlines across the country in 2013. They predicted “grave, long-term consequences” for the United States if this trend continues.

It’s difficult — even painful — to imagine UW–Madison without its iconic humanities departments, many of them ranked among the top twenty in the country. No one is suggesting that this will happen, but accounts of a nationwide crisis (and precipitous drops in enrollment in humanities programs at schools such as Stanford, Princeton, and Harvard) do make the possibility worth examining.

And these questions of relevance, of practical value, of cost-versus-benefit are not going away anytime soon. They’re being posed, nationwide, by governors, campus administrators, and members of Congress. They’re being voiced by parents who worry that the humanities are a luxury their kids can ill afford. They are made manifest in federal funding decisions and in President Obama’s belief that education in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) fields must be a priority.

Countering the questions is a perennial challenge for Susan Zaeske ’89, MA’92, PhD’97, associate dean for arts and humanities in UW–Madison’s College of Letters & Science. The classic arguments for the enduring value of the humanities — “They teach us about ourselves and help us understand what it means to be human” — must now be bolstered by straight talk about real-world impacts, she says. It’s not necessarily a new challenge, but it’s more urgent now.

“There are crucial connections to be made,” Zaeske says. “The Great Recession, the salaries for STEM grads, the world’s problems, the political rhetoric — all hold enormous sway. What we need to do is show how the humanities are essential to our future, that they make an enormous difference in our lives, and that we need them now more than ever.”

On a morning earlier this year, Caroline Levine, chair of UW–Madison’s English department, gazed pensively over Lake Mendota from her office in Helen C. White Hall, considering the future of the English major.

“It’s down,” she conceded, about enrollment in the major. “Humanities majors across the nation are down. It is a very large trend, partly because many students are shifting to STEM and business fields.”

Like many people who do a lot of analytical reading, Levine never talks about one moment in isolation. Discussing the so-called crisis in the humanities, she points out that in the realm of higher education, there are “big, unsettling changes” every twenty-five years or so. Although the English major is down in numbers the last several years, a century ago, there were no majors at all. By 1945, major degree fields — including philosophy, English, and history — had been firmly established and were on the rise.

“That was a big moment for the humanities,” she says, recalling the end of World War II. “You had all of these people coming into the university on the GI Bill who felt they had been denied access to these great works of culture. At that time, and even thirty years ago, I don’t think we worried as much about our students’ economic future.”

Data on a national downward trend are complicated. The percentage of students majoring in humanities has dropped from the 1970s, but it actually remains close to the average level of the past sixty-five years or so, in part because far more people are now going to college. The picture looks more worrisome at some schools where the humanities have traditionally been strong. Over the last decade, Harvard had a 20 percent decline in humanities majors, according to a 2013 New York Times article. And while 45 percent of Stanford’s faculty is clustered in the humanities, only 15 percent of its students can be found there these days. The most popular major at Stanford? Computer science. At UW–Madison, the most popular major is biology, with virtually all humanities majors (except for some of the languages) experiencing a slight decline over the last two years.

Is Levine worried? After all, the UW’s English department has been ranked among the top twenty in the country for decades, and can claim the likes of beloved professor Helen C. White, and successful writers Joyce Carol Oates MA’61 and Lorrie Moore. Levine pauses before answering. In the long term, no. But in the short term, “we are being realistic,” she says.

She ticks off steps the department is taking to attract more students and push the boundaries of the field — among them, hiring professors at home in the digital realm, retooling the entire major to reflect global texts and voices, and reaching across disciplines.

“This is a moment of discovery — of new voices from populations that weren’t there before, of literary people asking questions of the sciences,” she says. “How do we remake our relationship to the environment, for example? And there’s this digital revolution — we are really in a rich, visual storytelling culture now. At the same time, reading and writing are both incredibly hard. And we still have to teach those. Because they are not going away.”

John Rowe MS’67, PhD’70 grew up near Dodgeville, Wisconsin, and recently retired as chairman and chief executive officer of Exelon Corporation. He served in the prestigious role of co-chair of the commission that produced “The Heart of the Matter.”

Rowe, who has endowed two history chairs at UW–Madison and has a keen appreciation for the importance of the humanities in everyday life, says we are in no danger of losing them altogether. “It’s inconceivable — it won’t happen,” he says. “The history department at UW–Madison, for example, will not disappear. But we may be in danger of not funding the humanities as adequately as they need to be.”

Federal funding for the humanities peaked in 1979, at $461 million. It has been dropping ever since, and now totals less than $150 million. A House panel has suggested cutting the funding nearly in half this year. Meanwhile, funding for the National Science Foundation is in the billions. Why the disparity? Rowe points out that the sciences offer returns in tangible endeavors, while the value of the humanities can be harder to quantify. Yet this is nothing new.

“It’s not so much of a crisis as it is a chronic problem,” Rowe says. He believes the solution may rest in private funding rather than in federal dollars. “The money is out there,” he says. “The question is, how do faculty learn to organize themselves, reach out, and motivate others to share in the excitement of their endeavors?”

Zaeske agrees, citing current campus efforts that everyone — from parents to community members to employers — ought to know about. A new outlook is changing the way students read, write, and think about literature, history, and social issues. Humanists are exploring complex digital tools. Graduate students are reaching out to high school students, prisoners, seniors, and myriad other groups starving for access to transcendent ideas. And this is all taking place while the university continues to teach classic literature and foreign languages, emphasize the basics of good writing and close reading, and tout the pleasures of deep thinking and logical reasoning.

“In many ways, the humanities have never been more exciting than they are at this moment,” Zaeske says.

Remember Shakespeare’s The Tempest? While the humanities at UW–Madison are far from being washed overboard, they are undergoing a “sea-change,” and “something rich and strange” is emerging from the upheavals wrought by the Internet, globalization, and the economy. This emerging force, say faculty and administrators, is giving life to new ways of understanding our world and its people.

Jim Sweet, chair of the UW’s history department, envisions a bold new future for history grads. “We want our students to enter the workforce as multifaceted employees, equipped for a variety of different fields,” he says. “Part of that is understanding that Europe and the U.S are no longer the center of the universe.”

Sweet and his colleagues have been working for the last three years to create a transnational focus for the history major, expanding breadth requirements so students get full exposure to faculty with geographically diverse interests. As of 2012, UW–Madison has one of the largest concentrations of Asian specialists in the country, and many faculty are well versed in the languages and cultures of other rising countries.

“We take into account the entire world, including places that have risen to prominence economically and politically, like China, Brazil, India, and Russia,” says Sweet. “Transnationalism also considers the connections between those places — between China and South Africa, for example. That’s the world we’re all living in, and we want our undergraduates prepared to understand it.”

This aligns with key goals set forth in “The Heart of the Matter.” The authors recommend creating a National Competitive Act, which would fund education in international affairs and transnational studies. The report also urges colleges to build on and expand language learning to “equip the nation for leadership in an interconnected world.” UW–Madison is a leader in language education and research, offering dozens of languages from Arabic to Zulu, and there’s a strengthening focus on what are considered strategic languages, such as Russian and Chinese.

“Learning a language is not a luxury,” says Sweet. “It’s critical to becoming a global citizen.”

“Mashed-up, recombinant, and collaborative” is how English professor Jon McKenzie describes the fast-evolving discipline known as the digital humanities.

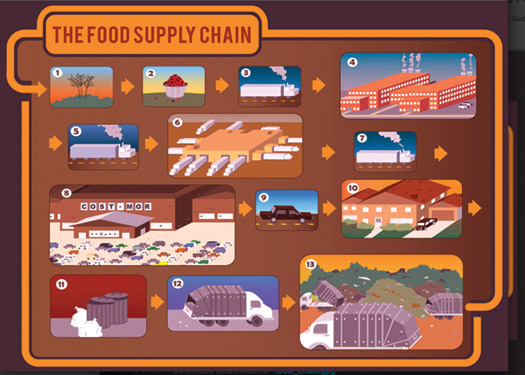

McKenzie runs DesignLab, a consulting center housed within UW–Madison’s College Library. There, digitally savvy professors and graduate students help undergraduates create projects with smart media, incorporating images, text, sound, and data to present ideas in different forms and reach diverse audiences. Think podcasts, video essays, and blogs.

“Students can write academic essays in their sleep,” says McKenzie. “I want students to produce more than papers. I want them to work in groups and produce a suite of projects.”

But digital humanities is about much more than creating with smart media. The Internet has rocked our world, changing the way we read, write, and learn. So profound has been its impact, according to McKenzie, that “you could compare it to the invention of the alphabet.”

The humanities offer a sweet spot for thinking about this rich, new-media universe, where students talk, create, listen, and share.

“Humanists are comfortable in this space,” says McKenzie. “We’re all about rhetoric, storytelling, creativity. We look at the big sweep — what is the Internet doing to our privacy, our notions of power, the traditional ways we teach and learn?”

That’s a realm that Mark Vareschi, an assistant professor of English, is eager to explore. Vareschi wanted his students to think about the ways people inhabit the worlds of Twitter, Facebook, and other online spaces. So he designed a course — Frankenstein, Robocop, Google: Human Memory/Digital Memory — in which students consider “the relative frailty of human memory in comparison to the unforgetting nature of digital storage.” In other words, you are what you post — or text, or tweet, or like.

“My students and I are grappling with an age-old humanities question of agency, or self,” says Vareschi. Google, he points out, has essentially created a “shadow self” for each of us by preserving each of our online interactions, no matter how mundane. “Everything is there,” he says. “Every message, post, chat, tag — most of which you don’t remember. But is it more frighteningly accurate than your own notion of yourself?”

Old questions, new universe, as Vareschi points out. But humanists are also turning to the computer to discover new questions — and to rethink their relationship with books and writing. Books hold words, and words are data. All of those data — millions and millions of words — are now available online. This means it is now possible for humanists to look for large-scale patterns by turning to some of the same software that scientists use to study genomes, for example, or cells.

It’s called data mining, a.k.a. humanities computing. Before 2009, virtually no students and few faculty had heard of it. Now, humanities computing is “the consummate academic hot-button topic,” according to an April 2014 article in Slate.

Humanities students today — and increasingly, their professors — have been using computers practically their whole lives. Software isn’t intimidating to them. In fact, says Catherine DeRose, a doctoral candidate in English, humanities computing may hold the key to revitalizing the humanities in many students’ eyes. “It’s a way to work with some skills they already have to study English texts in a new way,” she says. “If they want to be on the computer, then let’s figure out a way for them to study English with it.”

DeRose collaborated with fellow graduate students in the computer sciences department to create a “genre mapping tool” for her studies in nineteenth century British literature. Her filter captures cities mentioned by name in hundreds and hundreds of British novels — far more than she, or anyone else, could read. At first the place names are clustered thickly in Britain, as you’d expect. But the map morphs as she clicks through the years, showing cities across Europe, and even Asia, Africa, and North America.

“How did transportation innovations — or some other factor we haven’t considered — play a role in people’s reading and writing habits?” she asks. For scientists, outliers often represent error and are viewed with skepticism. But for humanists, DeRose says, “the outlier is often what’s most interesting.”

It’s interesting from a literary standpoint, but according to a 2011 article in Forbes, mining literary data may be one key to predicting human behavior in real life. Epidemiologists might study linguistic patterns to predict who is most vulnerable to diseases, for example. Bankers might use a similar descriptive analysis to determine who is a good or bad credit risk.

The Forbes article quotes Michael Witmore, formerly an English professor at UW–Madison, who launched a radical, computational approach to Shakespeare’s works when he was here. “When you’re dealing with human beings and language, there’s no place to hide,” he says. “We give away information in everything we say.”

The most radical departure from business as usual in the humanities? Taking scholarship public.

For decades, says Sara Guyer, director of the UW–Madison Center for the Humanities, “there was an assumption that if a student focused on publicly oriented work and communicated with audiences outside academia, they were, in some way, a failure.” The center was founded in 1999 to help break down that wall. Philosophy professor Steven Nadler, its first director, started with a public lecture series, Humanities without Boundaries, which still draws crowds. Then workshops sprang up to encourage faculty and graduate students to talk with each other about issues of race, disability, gender, labor, and more.

“We wanted to coax UW humanities people out of their disciplinary cocoons,” he says.

Such broad, multidisciplinary conversations about real-world problems are now considered by many to be vital to the nation’s future. “The Heart of the Matter” encourages humanities scholars to bring historical, ethical, literary, and aesthetic perspectives to bear on issues of climate change, obesity, world hunger, and more. Guyer’s center is now part of a new regional consortium based at the University of Illinois that has linked humanities centers at fifteen research universities in a challenge to rethink and reveal the Midwest as a key site — both now and in the past — in shaping global economies and cultures.

The center has also become a national model for what is now known as the public humanities, sponsoring major outreach initiatives that connect faculty and students with communities and populations — inmates, seniors, high school students, and teachers from rural areas — who might otherwise never have access to one another’s thinking. A 2012 article in the Chronicle of Higher Education called the center’s projects an “admirable example” of “PhDs turning their creative powers outward.”

The one crisis in the humanities that nobody disputes is the dismal academic job market. After “pausing their lives for six years to study English, history, and the like,” notes a 2013 article in the Atlantic, humanities PhDs are facing the shocking odds that upward of 43 percent will not receive offers to be postdoctoral researchers or professors.

The Center for the Humanities is turning this crisis into opportunity.

“Historically, advanced graduate training in the humanities has been a one-way street,” says Guyer. “It sends you right to a job in academia — or you are more or less invisible. We are changing that model.”

With a $1.1 million grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation in 2013–14, the center offers yearlong fellowships for PhDs at community organizations such as Wisconsin Public Radio, the Madison Children’s Museum, and the Madison Public Library. Instead of encouraging graduate students to tunnel ever deeper into their mines of specialization, these fellowships urge them to share what they know more broadly and to consider other work environments that could benefit from their scholarly approach.

But what about undergraduates? Parents, students, and even President Obama have expressed concern about lower starting salaries for humanities grads. A 2012 study showed English majors starting at $29,222, while engineering students earned more than $50,000 during their first year on the job. Is a humanities degree worth the cost — to the individual, to the school, to the economy? That, of course, depends on how one assigns value and defines success. First-year philosophy students learn to think about this kind of thing by discerning the difference between reason and judgment.

“Reason may tell you that the best approach is to maximize your income,” says Russ Shafer-Landau, chair of the philosophy department, who specializes in morality and ethics. “Judgment is about questioning the assumptions that most of us take for granted. Is more money better? Who says so? How do we assign value to various things in our lives?”

The good news: studying the humanities doesn’t mean you won’t get a high-paying job eventually. A study released by PayScale, Inc. surveyed 1.2 million people across the U.S. and found that in general, salaries for college graduates even out after ten to fifteen years of work experience. And in study after study, employers consistently place a high premium on the critical-thinking, problem-solving, and writing skills of humanities grads.

The biggest barrier to success in the job market for these grads is not knowing how to communicate their value. But that’s starting to change. Karl Scholz, dean of the College of Letters & Science, has launched a massive effort designed to boost career readiness by helping liberal arts majors identify their passions, articulate their skills, and connect with alumni who can help them.

“We want to help the conversation go more easily when a child tells a parent, ‘I want to major in philosophy,’ ” says Scholz. “With more information and self-knowledge, all of our students can better navigate the journey.”

Human beings are complex. We make choices. We nurture beliefs. We teach our children right from wrong, and we follow a moral code ourselves. But we also do terrible things. Why are we as a species — and as individuals — so deeply contradictory? Science can explain some of our behaviors, but the humanities help us attach meaning to them. And the search for meaning will always be a fundamental preoccupation of the human race.

So, are the humanities in crisis? Perhaps the best answer comes from the DesignLab’s Jon McKenzie.

“The humanities are the crisis,” he says firmly. “The upheaval is what we are all about.”

Mary Ellen Gabriel is a writer for the College of Letters & Science.

Published in the Winter 2014 issue

Comments

Ralph H Kurtzman. Jr. Ph.D. '69 November 25, 2014

This is an excellent article. However, I think there are many more things that need to be said. I had a 7th grade teacher, who with one posted quote showed that she was wiser than most (all?) politicians and many university administrators: “We are not educated to make a living, but to make a living worthwhile.” You can send text messages with no understanding of English, but in most endeavors, if you expect to advance, you must have more than a high school understanding. Without some understanding of philosophy, especially logic, your thinking will be crippled. That is why the highest, research degree is called a Ph.D. I hope that at some point more citizens of Wisconsin will understand political science more fully than they apparently have since the ’60s when Joe McCarthy was their leader in Washington. That brings us to what I see as the broadest of the humanities: history.

Here I need to first say that as an undergraduate I took one course in history, but as a graduate student, the most valuable course was a seminar in history of my major subject. Each of us had to present a seminar on a historical plant pathologist. I think it is very fair to say that anyone who does not know the history of the subject they majored in does not know the subject.

There is a very handy way that the humanities, particularly the history department can promote thier own subject and the quality of entering freshmen. I am thinking of support for National History Day in 6-12th grades. The University of Minnesota co-sponsors it with Minnesota Historical Society. The Histrorical Society has gained such support that they have nine full time employees (graduates in history) who help schools to support National History Day. Wisconsin Historical Society has one full time employee, Sarah Klentz Fallon, who does an amazing job, and one part time helper. The Minnesota Society was originally modelled after the Wisconsin Society, but cooperation has made both Minnesota institutions stronger.

Ralph H Kurtzman. Jr. Ph.D. '59 November 26, 2014

oops! two dumb errors my degree was ’59 and of course Joe McCarthy was the ’50s. By ’69 most people knew Joe’s “side kick,” “Tricky Dick Nixon.”