Hot Enough for You?

Statistics indicate heat waves are the deadliest weather.

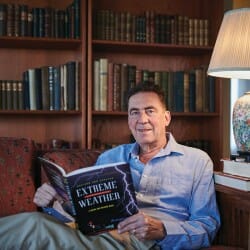

Blizzards are bad. Hurricanes are worse. But when it comes to killing power, no weather packs the punch of a heat wave, according to the numbers that Richard Keller has crunched.

Keller, an associate professor in the School of Medicine and Public Health, has been counting the dead from the heat wave that struck France in August 2003. That month, high temperatures in Paris climbed above 100 degrees Fahrenheit, with lows in the eighties. During that stretch, the nation saw its mortality rate shoot up by nearly 15,000 deaths.

“In terms of mortality, this is probably the worst natural disaster in the modern history of France,” Keller says, though he admits, “there may have been some droughts in the Middle Ages — accurate numbers are very hard to get from pre-modern times.”

Accurate numbers are difficult to get in modern times, as well, Keller notes. When some natural disasters hit, the death toll is fairly easy to count: bodies drowned in a flood, for instance, or crushed by falling buildings in an earthquake. But heat is a more insidious killer.

“You can only tell if a person dies of heat stroke if you’re actually there when they die,” Keller says. “Plus, during a heat wave, more people die of things like drowning — the warmer it is, the more people go swimming, and when more people swim, more people drown.”

Keller used numbers that French demographers came up with to measure excess deaths — that is, the total number of people who died in France in August 2003, as compared to the average number of deaths in the same month in 2000, 2001, and 2002. The result was an increase of 14,802. “It’s a crude measurement, extremely blunt,” he says, but it’s the best overall calculation. Across Europe, the heat wave may have accounted for 70,000 excess deaths.

It wasn’t the daytime highs that seemed to be most deadly, Keller believes, but rather the low temperatures — which were actually very high, meaning that people who suffered all day found no relief at night.

“The houses in France, made of stone and brick, just retain heat,” he says. “People had no chance to recover.”

Today, France — as well as communities across the United States and elsewhere — pay greater attention to the danger of heat waves, mandating air conditioning in nursing homes and senior living facilities, and setting up “cooling centers” where the public can have access to air-conditioning. But Keller notes that such measures may have little effect.

“The people who were most affected by the heat were the socially vulnerable: the elderly, the poor, and those who live alone,” he says. “They often don’t take advantage of cooling centers or have people to look in on them and encourage them to seek relief.”

Published in the Winter 2012 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.