Great Fall of China

Should a Chinese couple have one baby? Two? More? Fuxian Yi and his homeland are at odds over children.

More than 6,000 miles from his home country, the People’s Republic of China, Fuxian Yi receives messages on social media from panicked women. All have differing versions of a similar dilemma.

They’re pregnant. Illegally.

One woman, concealing the pregnancy of her second child from her employer, fears that officials will subject her to a forced abortion if she’s found out. She could lose her baby, her job, her relationships, and her home.

Yi offers the best guidance he can: Take prenatal vitamins. Seek out sympathetic doctors. Reach out for help to lawyers and journalists — there’s a short list he trusts. Be brave; carry the pregnancy to full term.

A physician by training and a senior scientist at UW–Madison’s Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Yi has for years been a vocal advocate for abolishing the one-child policy in his native country. Beginning in 2016, China offered couples the right to ask for permission to have a second child, but even as the population-control policy relaxes, Yi continues to call on the Chinese government to scrap it altogether.

Yi treats China like a patient: he’s spent 17 years evaluating and diagnosing the world’s most populous nation, and what he’s found has turned him into a dissonant and powerful voice in the debate about its one-child policy. And according to his calculations and projections, his patient’s outlook isn’t promising.

“The policy is associated with some of the most severe human rights transgressions in the world today,” Yi says. “From an OB/GYN perspective alone, it is directly or indirectly responsible for some of the six to 14 million abortions in China annually.”

For the last four decades, authorities across China have been accused of intimidating women, as well as practicing forced abortions, even in late-term pregnancy at eight months and beyond. This alone draws deep international criticism, but equally startling is Yi’s research, which concludes that not only will population growth slow — which is precisely the aim of the policy — but the trend will accelerate and cause China’s population to fall into steep decline.

Essentially, China’s family-planning policies will undermine the country’s social stability and sustainable development right at the peak of its economic boom.

Yi’s population research and predictions differ from those of the Chinese government, and his accuracy has made him controversial. His first book on the topic, Big Country with an Empty Nest, was banned from mainland China after its publication in 2007 in Hong Kong due to its strong criticism of the one-child policy, the policy’s history, and, by inference, the government’s tight grip on family planning.

Fearing punishment if caught on Chinese soil, Yi didn’t travel to his home country for 10 years. But international communication, accelerated by blogs and social media, are transforming his public image from traitor to truth-seeker. Now Yi and his views are slowly becoming more mainstream, thanks to gradual, changing attitudes in China. In recent years, he has regularly shared his opinions and data with 140,000 followers on Weibo, a Twitter-like platform in China. Some of his articles have racked up more than 10 million hits online.

In 2010, Yi returned to China. He didn’t exactly receive a warm welcome — the one-child policy was still in place — but he was invited to give 13 lectures at the country’s top universities. He discreetly attended a talk featuring a leading proponent of the one-child policy and original author of the “open letter” in 1980 that set that policy in motion. That official spoke disparagingly about Yi’s ideas.

“After the lecture, I followed him to the hallway,” Yi says. “I needed to talk to him because he drafted the open letter, and I wanted to know why he and other officials have secret meetings on this topic. He told me he would go to the bathroom first.”

Thirty minutes passed. The official didn’t return. Yi later learned the official snuck out of the building’s back door. Yi heard from a friend soon after that the police were supposedly searching for him. Sensing he should leave immediately, he fled by train to Shanghai.

All Yi wanted to do was discuss the facts.

The Doctor Is In

When talking about his family — his parents, siblings, wife, and three children — Yi flashes a sprightly smile and expressive eyebrows behind brown-rimmed glasses. He jokes about how simple his needs are: a green landscape, like Madison’s in the summer, which reminds him of the lush scenery of the village he grew up in. And personal freedom, something he feels should be a right for all people.

As one of seven children growing up in rural Hunan, Yi was isolated by mountainous terrain. China’s enormity and diversity leave it decentralized and often shaped by the interpretations and agendas of provincial and village leadership, making his home more tolerant of dissent, but also miles away from electricity and modern medicine.

When Yi was an adolescent in the 1980s, he and his family were shocked by the sudden death of his sister-in-law.

“I wanted to save her life — even as a high-schooler. I felt very sad,” Yi reflects. “Life is so short. Her son, my nephew, was only a couple of years old.”

The tragedy inspired Yi to drop his focus in economics and enroll at Hunan Medical University, an institution cofounded by Yale University in 1914 to improve people’s lives.

Over time, Yi’s optimism for general medicine evolved into a passion for medical research, increasing the number of lives his work could affect. He swapped his stethoscope for a microscope and pursued a master’s degree and PhD in pharmacology from the same university.

In 1999, postdoctoral positions at the University of Minnesota–Twin Cities and the Medical College of Wisconsin brought Yi to the United States. By then, his wife had given birth to his oldest child, a girl. The couple relished being free from the one-child policy; they had two boys in the following decade.

Yi’s reputation as a skilled researcher landed him a position at UW–Madison, in a lab focused on improving health outcomes of women and their babies. In 2002, he began studying preeclampsia, a medical condition that causes hypertension in pregnant women and puts the health of mother and baby at risk. He’s become one of a handful of experts who are proficient in using biological dyes to track preeclampsia-related dysfunction at the cellular level, looking at what happens when blood vessels over-constrict. Under Ian Bird, professor and vice chair of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Yi is a part of a team developing drugs that repair hormonal signals needed to make blood vessels function properly.

Bird had no idea about Yi’s extracurricular activity.

“A scientist working with a Chinese colleague of mine said to me, ‘You do know Fuxian is famous, right?’ This was four years after he started working with me,” says Bird, whose support for Yi expands beyond the lab bench. “He has millions of followers in China. I tell him that when he gets his Nobel Peace Prize, I want to carry his bags.”

Taking Vitals

To understand the health of their patients, doctors typically gather vitals: pulse, body temperature, blood pressure, respiration, and family health history. Similarly, Yi has adopted a biology-inspired framework to study China as though it were a living, breathing organism. He explores how several complex inputs can lead to flourishing or decay.

“If some disease has an effect, I want to understand it,” he says. “My philosophy for analyzing China’s population is looking at education, GDP, cost of living, housing, daycare, childbearing age, infertility — all the markers of health of a society, just like the health of the human body.”

Not all of Yi’s methods are entirely novel to the field; rather, it’s his holistic approach that’s brought him notoriety and controversy. When Yi released his first book, one of the claims he tackled was from the country’s National Population and Family Planning Commission, which stated that without family planning, China’s population would surge to 4 billion people by 2050. Yi’s research suggests the claim lacked validity and can be viewed as good intentions gone awry.

Yi knew as an MD that the infertility rate in China had increased by tenfold in the previous 30 years. Now one in every eight couples is physically infertile. Then there are social factors to consider, including a growing middle class with equally growing appetites for wealth and comfort, increasing costs of raising children, delayed childbearing, and the country’s aging population. By using multiple diagnostic indicators, Yi argues that had the population control policy been scrapped completely in 1980, China’s population would have peaked at about 1.6 billion — not 4 billion — and then gradually declined, meaning no population-control policy was necessary to accomplish what the government set out to achieve.

When Yi first began to share his research with demographers and officials in the early 2000s, they figured his conclusion was the outlier, not theirs. But after Yi began blogging about his experiences, interest spread until his posts and articles reached millions of people. Media calls poured in, focusing on the consequences of China’s rapidly aging population.

In 2013, a new edition of Yi’s book was released by a publisher under the Chinese State Council and was picked as one of the 10 best books by Xinhua News agency, China’s largest official press agency. The government, institutions of higher education, and libraries have all requested copies for their collections.

Then came invitations to regional and global conferences. Yi has spoken at the 2016 Boao Forum for Asia, an event for thought-leaders in government (including China’s prime minister), industry, and academia. And he has been interviewed by hundreds of media, such as the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, National Public Radio, and the British Broadcasting Corporation. He has submitted research to peer-reviewed journals in China and sent copies to almost every member of the national parliament, many of whom expressed support and began submitting policy proposals based on his work.

Yet it’s unlikely the government will publicly support Yi. Instead, he has noticed that official predictions are tweaked each year and are gradually matching his findings.

“Some officials in the family-planning committee reached out to me by email but didn’t want the public to know,” Yi says. “One person said, ‘I totally agree with you,’ but later on TV, he had to make a speech emphasizing the importance of the one-child policy.”

Symptoms (and Systems) of Control

Yi considers China’s family-planning policies symptomatic of a political culture that’s still averse to dissent and entrenched in control. The 1994 International Conference on Population and Development put an end to the concept of population control and prohibits all forms of quotas, coercion, and violence. But even though China relaxed its limit to two children in 2016, it is still imposed in the form of quotas, and it’s unclear whether the policy will continue to support forced abortions, coercion, and violence.

Such threats hit close to home for Yi in 2006, when a relative conceived a second baby by chance and went into hiding during her last trimester to avoid detection. Eventually, she was detained, hospitalized, and slated for a forced abortion. Yi was able to arrange her escape. But another relative was not as fortunate. Yi says local authorities boasted about her forced abortion as a “political accomplishment.” The relative’s name was made public to deter others considering an illegal pregnancy.

Jiaxian Huang, Yi’s wife, says many of his critics don’t understand that speaking out against the policy poses risks, even thousands of miles away. “He is doing something they can’t understand,” she says. “He focuses on the whole country and the future of the world.”

In 2015, Yi was blocked by China’s National Health and Family Planning Commission (NHFPC) from publishing his third and fourth books. In recent months, Yi’s blogs and social media accounts hosted by companies in China were also shut down at NHFPC’s request. But he says that severing his access won’t stop the movement. As the data pile up, the prognosis for China’s population isn’t good.

Jonathan Song, a friend of Yi’s, remains inspired by the lengths Yi has taken to stay connected to the issue and save lives.

“Even being far away in the U.S., he has a sense of responsibility and cares about people and the pressure they face,” Song says. “The government shouldn’t push its hand into the body.”

On Borrowed Time?

Despite China’s expansion of the two-child policy, the majority of couples still aren’t buying it. And, Yi fears, it might be too little, too late.

It comes down to Total Fertility Rate (TFR), or the average number of children birthed by one woman. In order for populations in developed countries to maintain themselves, the TFR needs to be around 2.1, where each couple has around two children to replace them. But not all children grow up to have children of their own. Because China’s infant mortality rate is higher than in other developed countries, it needs a higher TFR (around 2.2) in order to replace its population. Yi says the forces that drive the rate are similar to the kinetic energy and momentum that govern an object when it rolls off a cliff: if it slips below replacement rate, a country’s population could fall into decline.

There are several inputs that factor into the equation, only one of which is a government’s decision to implement population-control policies.

“TFR declines as socioeconomic level increases,” says Yi. “Even if China did not implement family planning, TFR would decline spontaneously with economic development.”

This is why China is far from alone in facing population decline challenges. The United States (where TFR is 1.84), Russia, Japan, and South Korea are also projected to experience population declines, albeit at slower rates. These declines will gradually shrink these nations’ workforces and economies.

China has already been pushed off the metaphoric cliff with its population decline, says Yi. What’s unique about China’s decline compared to other countries is its speed. Survey data suggest that China’s TFR was as low as 1.05 as of 2015. It might, under the two-child policy, temporarily rise to 1.3 in 2017, but the population will still decline in the long run.

Having just one or no children at all has become the social norm in China. For decades, China’s economy has catered mostly to one-child families, creating greater demands (and prices) for commodities such as housing and education.

With little time to adjust, the coming labor crash could send economic shockwaves throughout the global marketplace. China wanted fewer people in an effort to alleviate its fear of overpopulation. However, Yi believes, its policies will cause China to lose economic vitality and increase instability. It will lose the ability to adapt.

A couple decades from now, Yi thinks the world, China included, will look back on China’s population-control policy and wonder why humans made such a stupid choice. He wonders if we’ll look back to reflect on the loss of life and potential, both personal and societal, of those negatively affected by the policy — a policy he thinks wantonly violates morality, both individually and collectively.

“Beauty is life,” he declares, “and every life is different. Every human has a different idea.”

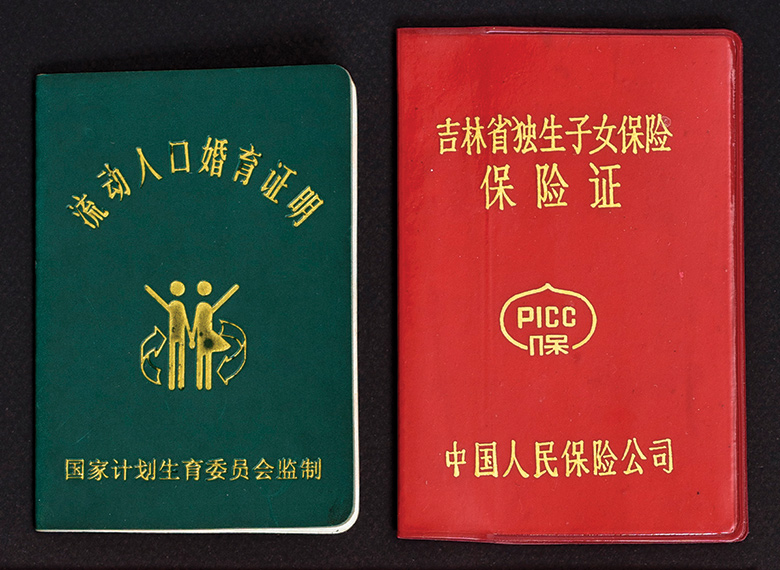

(Left) Marital and childbearing status certificate for the floating population (people who live in one region but, for census purposes, are officially counted as living in another) (Right) “One-Child Insurance Certificate” — the Chinese government pays some insurance premiums for families that have only one child.

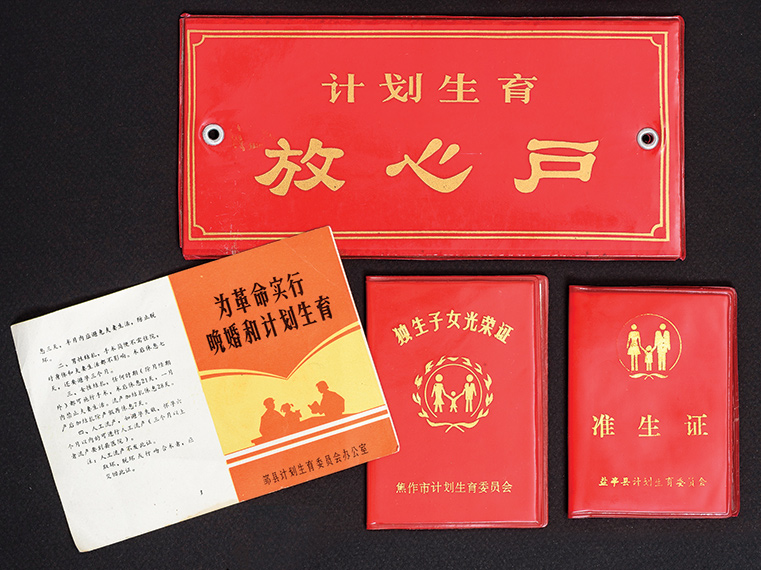

(Clockwise from top) This plate reads “Trustable family for population control policy”; such plates signify homes where a couple has voluntarily complied with population-control policies. Birth permit (1990) — in China, couples have to apply for such a permit before pregnancy. Certificate of Honor for One-Child Parents. Proof of surgical ligation or IUD insertion for the purposes of birth control.

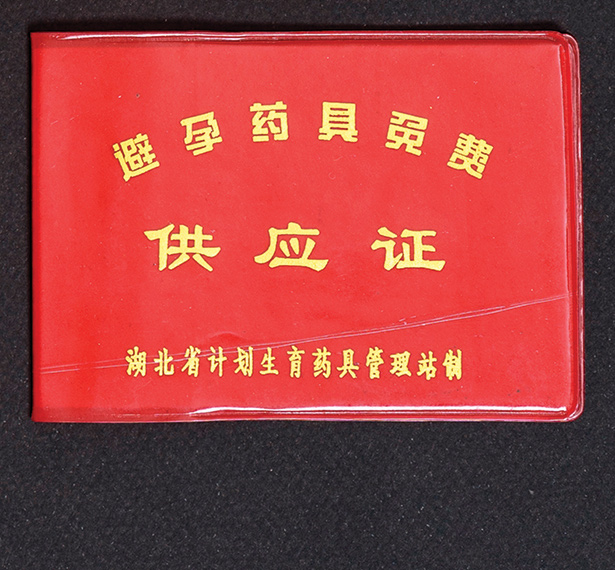

This document entitles the bearer to a free supply of contraceptives.

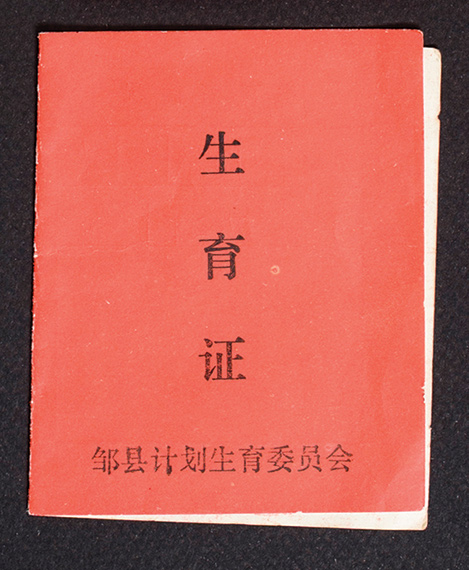

1985 birth permit.

Badge of the China Family Planning Association.

Writer Marianne Spoon MA’11 lives in Madison.

Published in the Summer 2017 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.