Finding a Home in Theater

John Malpede ’68 has turned to the arts to provide community, confidence, and stability for the unhoused.

A New Orleans–style marching band leads a group of performers through the streets of Skid Row in downtown Los Angeles. When they stop in front of a building on Crocker Street, several performers in eclectic costumes take their places at microphones set up on the sidewalk. This is the sixth stop for the theater troupe known as the Los Angeles Poverty Department (LAPD). It’s LAPD’s 2022 Walk the Talk parade to honor community members who’ve made contributions to the Skid Row neighborhood.

John Malpede ’68, in a red-and-white-striped shirt, sunglasses, and a long white scarf draped around his neck, points across the street. “This building is going to be knocked down and turned into supportive housing,” he tells the crowd assembled in the street. “They’ve got Crushow to make a mural on the building.”

Crushow Herring, a former college basketball star and unhoused resident of Skid Row, still lives in the neighborhood, where his “portraits of freedom” murals have become widespread and well known. He’s also a community organizer who helps people find jobs.

Three other men join Malpede in a quick performance, each speaking in the character of Crushow and telling his story. After a tryout with the NBA’s Los Angeles Clippers, Crushow sold dope in Skid Row. He quit dealing when his son was born in 2004. A friend recruited him to play in a three-on-three basketball league in Skid Row, where one of the players challenged him to give back to the community. That got Crushow started on his murals. In the process, he found his purpose through art.

The performance provides a synopsis of what Malpede has done with the Los Angeles Poverty Department, which he started in 1985 as the first performance group in the nation composed mainly of homeless and formerly homeless people. For almost 40 years, the performing artist has been giving residents of Skid Row a means to tell their stories through artistic expression — visual, performing, and multimedia.

Rooted in his fundamental belief that all people are multidimensional and creative, he’s given a voice to the voiceless. In doing so, he’s raised awareness about the lives and needs of the unhoused, given their art credibility, created community, and restored dignity and purpose to people often marginalized and adrift.

Birth of an “Artivist”

Homelessness in the United States has reached epic proportions because of a variety of factors, including rising rents, discrimination against subsidized housing applications, untreated mental illness, and persistent addiction. More than 600,000 people around the country are experiencing homelessness — the most since the federal government started tracking the number annually in 2007.

Malpede has situated himself at the heart of the problem. Los Angeles, long known as the “Homeless Capital of the World,” had the nation’s largest unhoused population in 2022, according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. And it’s getting worse. In 2023, homelessness in Los Angeles County rose 9 percent, to an estimated 75,518 people. Within the city limits, it rose by 10 percent, based on a survey by the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority. The majority of the city’s unhoused population lives in Skid Row, a 50-block area downtown with the highest concentration of people experiencing homelessness of any neighborhood in the country.

All of which makes Malpede’s work with LAPD more urgent and poignant.

This isn’t the first time that our nation has seen an uptick in unhoused people. Like many others, Malpede began to notice a surge in the number of people sleeping on the streets around 1983, driven by policies such as deep cuts to federal housing assistance. At the time, Malpede was traveling between New York City, where he worked as a performance artist, and Los Angeles, where he was dating someone. His time at UW–Madison, as a philosophy major in the late ’60s when the campus was charged with political debate and protests, had opened his eyes to community engagement.

“It was really a 24-hour education,” he says. “For the first time in my life, I was paying more attention to and participating in the adult, civic world.”

So, confronted by the wave of unhoused people a little more than a decade later, he felt driven to find a tangible response. He began work on a performance about homelessness commissioned by the nonprofit arts organization Creative Time to stage in New York City. While in Los Angeles writing the script, he attended hearings of the LA County Board of Supervisors. There he met and joined a group of Skid Row residents and advocates who were detailing the squalid conditions in county housing provided for unhoused welfare applicants. Malpede found the work compelling, and ultimately, he ended up in Los Angeles, where his lobbying effort led to a job as an advocate to make sure people were getting the welfare benefits due them under the law. He also continued his work as a performance artist. The possibilities of blending art and activism to improve the community inspired the creation of the Los Angeles Poverty Department and his work as an “artivist.”

Kaleidoscope Community

During his early days in Los Angeles, the better Malpede got to know unhoused people, the greater the kinship he felt with them, and a mutual trust developed. Yet, where he saw a kaleidoscope of experiences and personalities, society at large wanted to flatten homeless people into a single dimension.

“Working in Skid Row, you open up to the infinite capacity of every single human being,” he says. “Every individual has a million stories, and that’s what’s so beautiful.”

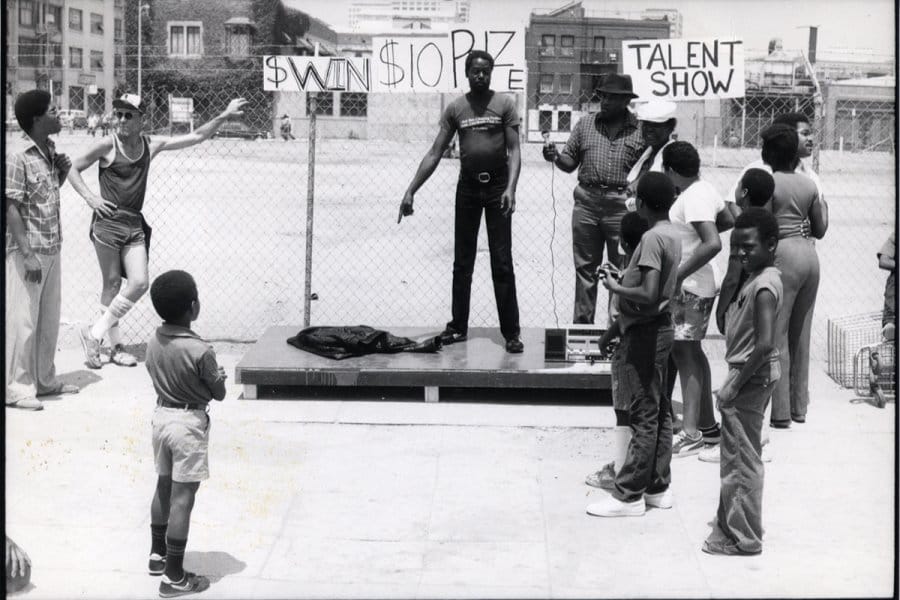

Malpede wanted to give those individuals the chance to tell their stories and influence the decisions shaping their neighborhood. In 1985, he secured a grant from the California Arts Council to conduct theater workshops in the area, and LAPD was born. The name was meant to contrast the often negative perception of the police department, what the artists jokingly refer to as “the other LAPD.”

“It’s always been about making artworks and performances that connect the lived experience of people in Skid Row to the larger social policies impinging upon their life experience,” he says.

During a phone interview, Malpede’s thoughts rambled in a raspy baritone, sometimes as disheveled as his wavy gray hair. Yet his passion for his life’s work is never in question. And at 78, he shows no signs of slowing down. As LAPD’s artistic director, he draws a modest salary from the nonprofit, which is funded primarily by grants. He’s supplemented that income over the years with teaching stints and residencies at UCLA, NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts, and the Amsterdam School for Advanced Research in Theater and Dance, among others. His work has garnered several honors, including the LA Stage Alliance Ovation Award and a Bessie award from New York’s Dance Theater Workshop in the Choreographer/Creator category.

While he was teaching in Amsterdam, Malpede met theater and dance artist Henriëtte Brouwers, now LAPD’s associate director. They’ve been married 23 years and have collaborated on a number of projects. When not collaborating on art, they hike in the mountains and bike to the beach. They have a small garden at their home in Mara Vista, and Malpede stays grounded doing tai chi.

The Power of Drama

Over the years, LAPD has staged myriad performances and exhibits throughout the city, hosted community conversations, and lobbied for the interests of Skid Row residents, blending art with activism to preserve and improve the community. That’s rooted in the spirit of ’76, when the neighborhood faced extinction — the city planned to bulldoze it amid a wave of urban renewal. A coalition of advocates, concerned that the low-income housing would never be replaced and Skid Row residents would be permanently displaced, successfully lobbied city officials to renovate existing housing and protect the area.

Since its inception in 1985, LAPD has used art and community engagement to circumvent continued efforts to develop the neighborhood. For example, in 2017, when city planners proposed to open all of Skid Row to market-rate development, Malpede and LAPD installed a nine-hole miniature golf course in its art space, the Skid Row History Museum & Archive, and then invited the entire department of city planning to play the course and attend a performance of The Back 9: Golf and Zoning Policy in Los Angeles.

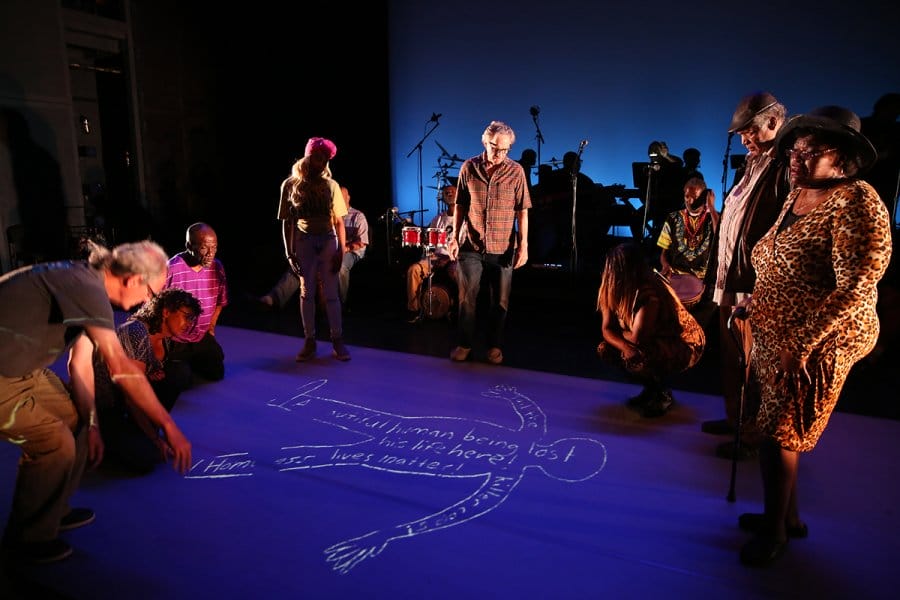

The performance, written by Malpede and Skid Row performers and directed by Malpede and Brouwers, portrayed backroom development deals made on the golf course, away from public scrutiny. At one point during The Back 9, a developer named Tom Buildmore tells a city council member, “The most important thing is to stop any more housing or social services from coming to downtown” — thrusting a cigar to emphasize his point. Through that performance and community conversations, LAPD succeeded in getting the department’s commissioners to change their plan.

They nixed the open-market development and committed to residents’ requests for more green spaces and stoplight adjustments for people who needed additional time to cross streets. “We got them to come to our events and meet people from Skid Row and find out what people would want in their neighborhood, as opposed to earlier plans designed for someone else,” Malpede says.

In 2013 Malpede spearheaded another LAPD community activism project involving a vacant storefront on Main Street, the western border of Skid Row. A nonprofit developer of housing for the formerly homeless planned to rent the retail space to the Department of Mental Health. But a for-profit developer who was converting vacant commercial spaces into lofts obtained a zoning variance to open a bar and restaurant in the space that would cater to the upscale tenants he hoped to attract. Skid Row residents appealed the variance before the zoning commission, arguing that a mental health clinic would better serve their interests. “Surprisingly, the commissioners were moved, and they agreed with us,” Malpede says.

He converted the transcript from the hearing into What Fuels Development, a performance that LAPD staged in conjunction with an exhibit at the Armory Center for the Arts. “It was an example where the show chronicled the impact we’d already had,” he says.

Recovery is a recurring theme in LAPD works. While many Skid Row residents struggle with addiction, Malpede and others believe the police characterize the neighborhood as a free-for-all drug zone, playing up stereotypes and instilling fear among outsiders. “Even though there are people on the street selling and using drugs, there’s also a highly sophisticated recovery community,” he points out.

In response to a police crackdown in the neighborhood, LAPD staged The Biggest Recovery Community Anywhere, a performance and film series that transformed the police narrative about Skid Row. “Everybody talks about it as a recovery neighborhood now,” Malpede says.

LAPD’s latest project, Welcome to the COVID Hotel, which opened in March, has involved panel discussions on housing as health care, an exhibit, a publication, and a performance chronicling unexpected lessons about health care for the homeless that emerged from the COVID-19 crisis. For many experiencing homelessness during the pandemic, the county’s efforts to house them temporarily in hotels — while seeking more permanent solutions — and provide free medical care marked the first time they’d received health care from caring individuals. The experience engendered trust that saved lives and led to housing solutions for some.

“Nothing Good Would Happen Without Naïveté”

Malpede is much more comfortable collaborating and performing than talking about his good works. Those include providing food, clothes, blankets, and an ear to those in need. “He’s the welcome mat,” says Stephanie Bell, a musical artist who’s performed in 20 to 25 shows with LAPD since 1996. “The man is amazing. He helps you not just in your art but also if you have a problem or a situation. John Malpede is like my second dad.”

Lee Maupin, a James Brown impersonator and Skid Row resident, had been dancing since he was three years old but knew nothing about acting until he met Malpede 12 years ago. Malpede, unconcerned by Maupin’s lack of experience, welcomed him to perform with LAPD. That helped Maupin discover talent he didn’t know he had.

“I never [knew] that I could be an actor, but John helped me to hone my craft,” he says. “He’s a good teacher. It’s got to where a whole lot of people think I’m pretty good at this stuff.”

Malpede had no idea where LAPD would go when he founded it. He has joked, “It’s a harebrained idea that wouldn’t die,” poking fun at his unfounded optimism at the time.

“I don’t want to minimize the virtue of naïveté,” he says. “Nothing good would happen without naïveté.”

Rooted in his fundamental belief that all people are multidimensional and creative, he's given a voice to the voiceless.

David Blumenkrantz, a teacher at California State University–Northridge and photographer who’s recently become involved with LAPD, points to Malpede’s unassuming, low-key but efficient manner as an effective means to getting things done — from making unhoused people feel at home and valued to setting up cooling stations where people can take refuge in the heat of summer.

In an Amazon synopsis of his book Acting Like It Matters: John Malpede and the Los Angeles Poverty Department, the author James McEnteer writes, “Malpede knows that residents of Skid Row, the most vulnerable among us, are the canaries in the coal-mine of our culture, harbingers of alienation and futility that now threaten middle-class stability and even survival. Malpede long ago recognized homelessness as a symptom of a society in trouble.”

McEnteer makes the case that Malpede has returned theater to the mission envisioned by the ancient Greeks, who thought politics were too important to leave to the politicians and produced plays about topical issues important to the citizens of the day. He contrasts this to the escapism of much modern popular entertainment and quotes noted theater director Peter Sellars, who says that Malpede’s work “will testify on the side of the angels.”

In The Real Deal, a documentary about the theater group, Sellars says, “When they look back in 100 years, the only theater being done now which will matter will be the work John Malpede is doing with the LAPD.”

John Rosengren is a Minneapolis freelance journalist and Pulitzer nominee. His latest book is The Greatest Summer in Baseball History: How the ’73 Season Changed Us Forever.

Published in the Fall 2024 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.