These Boots Were Made for History

Retrace the steps of UW limnologist Harriet Bell Merrill 1890, who defied the doubters to conduct pioneering fieldwork in South America.

In July 1902, the weary passengers of the cockroach-infested S.S. Byron were eager to depart the filthy cargo liner as it approached the Brazilian coastline. But a yellow flag was hoisted at the intended port, signaling the presence of bubonic plague.

“I feel more foolhardy than brave at this point,” wrote Harriet Bell Merrill 1890, who endured the Byron in order to collect insects, tiny animals, and plants from South American lakes and rivers. “Wherever I land, the threat of cholera, malaria, and the plague are prevalent.”

Despite her private worries, Merrill pulled up her bootstraps — literally — when the ship eventually came ashore. She wore a heavy pair of men’s Oxford boots that drew stares from both locals and fellow travelers, and for the next year, those boots carried Merrill almost 2,000 miles through remote parts of Brazil, Paraguay, and Argentina. She collected hundreds of plant and animal specimens along the way, many of them previously unknown to science, as well as cultural objects for the Milwaukee Public Museum.

Merrill was almost certainly the first professionally trained limnologist to conduct fieldwork in Brazil — and probably everywhere she traveled.

Matthew Berigan ’83, an independent historian now living in Brazil, stumbled upon Merrill’s name while searching for the papers of another UW–trained limnologist, Stillman Wright PhD’28, who conducted the first large-scale survey of northeastern Brazil. It’s likely Merrill’s notes and connections helped to pave the way for Wright’s work, and Berigan hopes that revitalizing the memory of these two scientists will inspire the next generation in both Wisconsin and South America.

“The legacy of inspired curiosity comes from people like Merrill and Wright dedicated to searching out what makes our world tick,” he says.

***

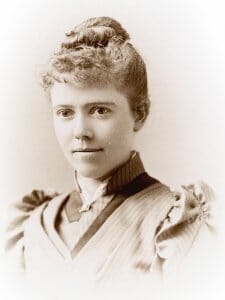

Merrill’s brother told her that it was “entirely out of the question for a petite little woman to hazard such a rigorous venture.” Wisconsin Historical Society, WHY-10804

Known to friends as “Hattie Bell,” Merrill was born in Stevens Point, Wisconsin, in 1863. She grew up exploring the Wisconsin River with her brothers and collected insects, rocks, and plants to study under her microscope. Her childhood passion inspired Merrill to become a high school science teacher in Milwaukee, and later to complete a bachelor’s degree at the UW and a master’s at the University of Chicago. After publishing a monograph on Daphnia, a genus of water fleas that filter particles out of lake water, Merrill was invited to become an assistant professor in the burgeoning limnology department at the UW. Founding department chair Edward Birge, later UW–Madison president, became a close mentor and was supportive of Merrill’s long-held dream to conduct fieldwork abroad.

Birge’s encouragement was a crucial counterweight to the many friends and family who tried to dissuade Merrill from traveling. One brother called her plans irresponsible and told her, “It is entirely out of the question for a petite little woman to hazard such a rigorous venture on her own.” Another brother begged her to postpone the trip until it was convenient for him to accompany her as a chaperone.

Merrill ignored them both. “In spite of all the deterrents, I am ready to roll to Rio,” she wrote shortly before her departure.

She proved to be a hardy traveler, even in the roughest of conditions. Fellow expats advised her to “steep herself in whiskey” to fend off yellow fever. During her nights in the field, Merrill was harassed by giant praying mantises, surrounded by caimans, and besieged by fire ants. She trekked for miles on horseback — and by Oxford boot — to reach Iguazú Falls, becoming one of the first Western women to ever behold the monumental waterfalls.

In 1907, Merrill returned to Brazil for another expedition through Venezuela, Trinidad, British Guiana, and Curaçao. “I keep hunting for the ‘unseen’ through the rain forests and waterways,” she wrote to Birge. “One cannot help but witness the coexistence of beauty with despair in the ecological struggle of procreation in this environment.”

After her second trip, Merrill left the UW to pursue a doctorate at the University of Illinois, but during her studies, a genetic heart condition worsened rapidly. Merrill died in 1915 at age 52. Her letters and field notes were preserved by relatives and colleagues, and her grandniece, the late Merrillyn Hartridge, eventually compiled and donated them to the Wisconsin Historical Society.

“Harriet was a persistent, independent woman, afraid of no potential dangers in any country,” wrote Hartridge in her biography of Merrill. “She died with her boots on.”

Sandra Knisely Barnidge ’09, MA’13 is a freelance writer currently based in Alabama.

Published in the Summer 2022 issue

Comments

Valerie January 16, 2024

Clarification-Merrill received her B.S. in 1890 and her Masters of Science degree in 1893 from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The staged photograph shown is from after that date, probably 1903. Yes she wore boots but so did men scientists, why make such a point about it? If you are doing research on this remarkable scientist, don’t use the god-awful book penned by TV writer/niece Hartridge as a primary document. Hartridge re-wrote every letter of Merrill’s in her own silly words.

Lynn March 27, 2024

“The Anandrous Journey.- Revealing Letters to a Mentor” by author M. L. Hartridge resulted from her search for the specific purpose behind Hattie Bell Merrill’s travels and the contributions she made to the field of limnology. Hartridge had Merrill’s photos, personal letters and newspaper articles, but the specifics of Merrill’s scientific research is something Hartridge continued to pursue. That search lead to successfully locating the Birge/Merrill papers. Paleolimnologist Professor David G. Frey of the University of Indiana just happened to be using Merrill’s notebooks and letters in his research at the very time Hartridge contacted him. An unbelievable coincidence!

The “Anandrous Journey” resurrected a woman who dedicated her life to science. With the publication of Hartridge’s book, Merrill was no longer an unsung heroine. Her South American travels, the photos she took, the people she met, her research and the rare samples she collected were all made known for the first time. As Dr. Arthur Hasler wrote, “ Merrillyn Hartridge’s thorough evaluation of this woman’s career presents a role model that will inspire our generation of women scientists.”

(Clarification of the clarification: Stated on pg. ix is that the M.S. Degree was from the UW of Wisconsin 1893 )

(Clarification – Hattie Belle Merrill was a petite woman and had a feminine side (not silly) in addition to her scientific pursuits. )