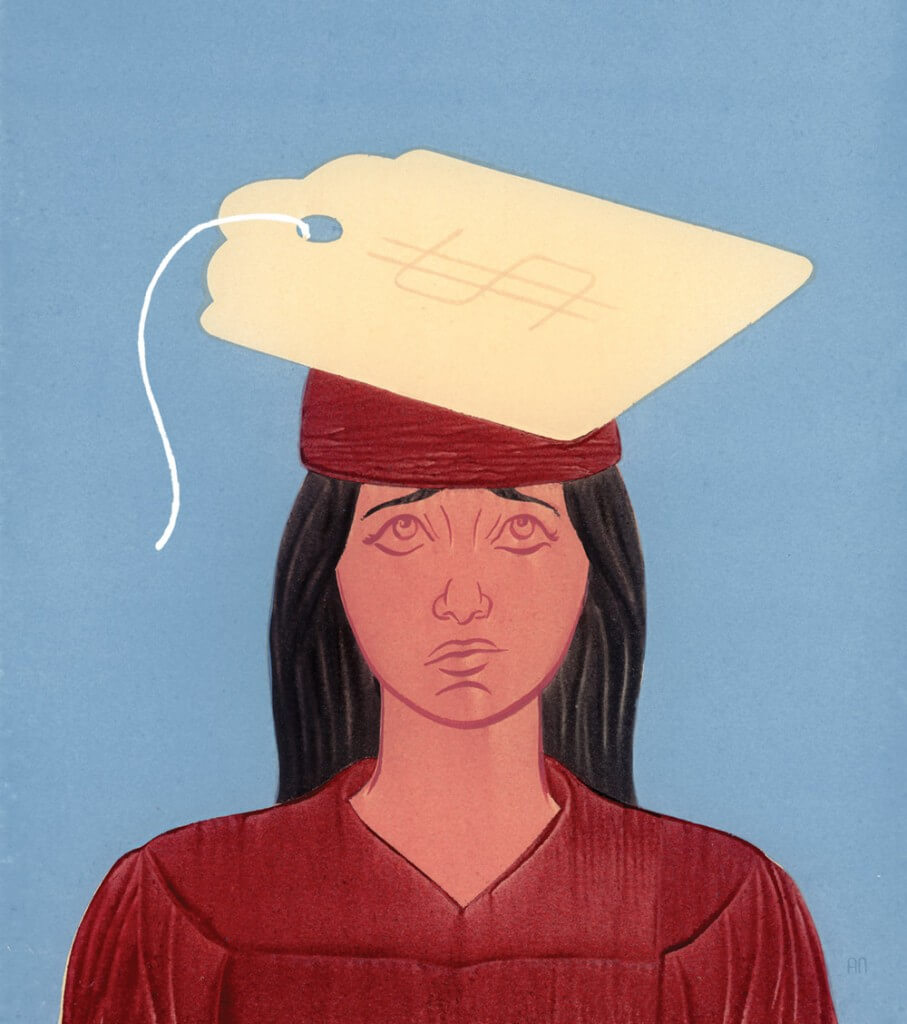

The Price Is Right

Who decides how much college tuition will be each year? Why does it keep going up (and up)? Is it worth the price? Studies — and graduates — say yes.

Once upon a time, students could make enough money to cover the entire cost of going to college by working during their summer and winter breaks.

These days, that sounds like a fairy tale.

Consider this recent headline from the Onion, which didn’t quite feel like satire: “New Parents Wisely Start College Fund That Will Pay for 12 Weeks of Education.”

The price tag for attending college has increased dramatically over the last two decades, with tuition more than tripling at public universities between 1988 and 2008, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. That trend includes the UW, where tuition went up 140.6 percent between the 2002–03 and 2012–13 academic years.

About one-fourth of that increase was directly due to the Madison Initiative for Undergraduates (MIU), a program students approved to address access to classes, improve advising, and offer more financial aid.

The intense focus over ever-increasing tuition bills even prompted New York Senator Charles Schumer to suggest penalizing schools that don’t keep tuition costs within the rate of inflation. Yet frustrated students and parents continue to find ways to pay because they believe that a four-year degree is worth the expense — and there is plenty of evidence that they are right.

Millennials (those born in the 1980s and 1990s) with college degrees made $17,500 more in 2012 than peers with a high school diploma, and nine out of ten millennials with college degrees said college has paid off for them or it will in the future, according to the Pew Research Center.

How did we get here? Where do those tuition numbers come from, anyway? And, when all is said and done, is college a worthy investment?

Tuition through the Decades

| Academic year | Wisconsin resident | Nonresident |

|---|---|---|

| 1940–41 | $65 | $265 |

| 1950–51 | $120 | $420 |

| 1960–61 | $220 | $600 |

| 1970–71 | $508 | $1,798 |

| 1980–81 | $976 | $3,461 |

| 1990–91 | $2,108 | $6,832 |

| 2000–01 | $3,791 | $15,629 |

| 2010–11 | $8,987 | $24,237 |

Source: Office of Student Financial Aid

How much has tuition gone up? Why?

Between 1992 and 2012, UW–Madison tuition for full-time, in-state undergraduates increased at three times the rate of inflation.

This year, these students will pay $10,410 for tuition and fees to attend UW–Madison. (This compares with other familiar Wisconsin schools, such as Marquette University, which charges $35,930 for tuition and fees, and Beloit College, which charges $42,500.) Their peers from Minnesota will pay $13,197 — thanks to an ongoing reciprocity agreement between the two neighbors — and undergraduate students from other states will pay $26,660.

In Wisconsin, the state has allowed the university to raise tuition to cover increases in utility bills, the cost of fringe benefits (including rising health care costs), and salary increases provided under the state’s pay plan for university employees. In 2011, Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker signed a bill that ended collective bargaining for state and university employees and required them to pay a larger share of their health insurance. The law cut costs, but the UW System (and UW–Madison) did not get to keep their share of those savings. Rather, the money went back into the state’s general budget fund.

Tuition represents 16 percent of the UW’s budget; the rest is covered by a mix of federal money, private funds, grants, and support from the state. The amount of money the UW has received from state taxpayers increased between 2004 and 2014, but the share of the university’s budget from tax dollars has dwindled, much as it has at public universities around the country. During the 1973–74 academic year, 44 percent of UW–Madison’s budget came from the state. This year, it’s 16.7 percent. During the last decade, most tuition increases for UW students and their families were offset by state budget cuts, says Darrell Bazzell ’84, UW–Madison’s vice chancellor for finance and administration. “We’ve had significant increases without actually increasing our capacity and enhancing the quality of the educational experience,” he says.

When Bazzell talks about tuition, he also reflects on his father, who came from Milwaukee to attend the UW on the GI Bill and “received a fine education,” graduating with a degree in sociology in 1953. “I think you really have to look at this in a broader context and not simply around what the tuition increase was this year or the most recent year,” Bazzell says. “The social compact has changed over the years. … The commitment on the part of government to really keep college affordable — it isn’t there in the way it once was.”

Who sets tuition?

UW–Madison Chancellor Rebecca Blank and her counterparts at other UW System campuses cannot raise tuition. That authority belongs to the eighteen-member UW System Board of Regents.

Wisconsin’s governor appoints fourteen of the board’s members to staggered, seven-year terms. They include attorneys, corporate executives, business owners, community and nonprofit leaders, a former legislator, and a former state auditor. The governor also appoints two UW System students to serve two-year terms. The remaining members are the state’s elected superintendent of public instruction and the president or a representative of the Wisconsin Technical College System Board.

In 2012–13, nonresident undergrads paid 184 percent of their instructional costs while resident undergrads paid 66.7 percent (with freshmen and sophomores paying a higher share).

But while the power to set tuition rests with the regents, they don’t act in a vacuum. Tuition is on the table when the legislature debates a state budget every two years. If the budget provides less than the UW System requested, legislators know that future tuition rates could increase.

Some budgets have included provisions that directly affect tuition. In 1999, lawmakers provided the UW System with $28 million to offset a one-year freeze in resident undergraduate tuition. Two years later, lawmakers required the regents to raise tuition for nonresident undergraduates by 5 percent. In 2003, the budget limited tuition increases at UW–Madison to no more than $700. The UW is currently in the second year of a freeze dictated by state law.

What does tuition pay for? What doesn’t it pay for?

Former UW–Madison Chancellor John Wiley MS’65, PhD’68 once joked that cranes are the state bird of Wisconsin, referring to the wave of building projects on campus that began during his tenure and are continuing long after he left the office in 2008. The cranes still reach into the sky over campus, with construction in progress on a number of building projects, but none are funded with tuition dollars. The same goes for Badger athletics, which means tuition doesn’t pay for stadiums, uniforms, or salaries for coaches.

Bazzell says myths about how tuition is spent persist because people perceive that higher education is funded solely by two sources of revenue: tax dollars and tuition.

Tuition doesn’t cover the cost of university research. Federal money or private grants cover the cost of those activities. “We can’t spend those dollars on bricks and mortar, for example, or in other discretionary ways,” Bazzell says.

Here’s what tuition does help pay for: faculty who teach classes; teaching assistants; academic services, including student advising; and the campus library system. Tuition also pays for operating and maintaining campus buildings in which learning — via lectures, labs, and discussion sections — takes place. Yet at UW–Madison, tuition covers only 30.2 percent of instructional costs.

The Cost to Attend UW-Madison

| Wisconsin resident | Nonresident | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expense | Residence halls | Off campus | Residence halls | Off campus |

| Tuition and fees | $10,410 | $10,410 | $26,660 | $26,660 |

| Books and supplies | $1,200 | $1,200 | $1,200 | $1,200 |

| Room and board | $8,600 | $9,400 | $8,600 | $9,400 |

| Miscellaneous | $3,214 | $2,414 | $3,214 | $2,414 |

| Travel | $1,042 | $1,042 | $1,692 | $1,692 |

| Total | $24,466 | $24,466 | $41,366 | $41,366 |

Undergraduate business tuition is an additional $1,000, and undergraduate engineering tuition is an additional $1,400. There is an additional New Student fee of $200 for freshmen and $125 for transfer students.

Source: Office of Student Financial Aid

What does it actually cost to attend college?

Although tuition makes the headlines when reporting on the cost of college, it’s only part of the bottom line. For resident undergraduates at UW–Madison, tuition accounts for only 43 percent of the total bill. Students also need places to live, food to eat, textbooks and other sup-plies, and miscellaneous stuff. (Think cell phones, clothes, laundry, and entertainment.)

The average cost to live in a University Housing residence hall per year, including food, is $8,600, though it ranges from $8,546 to $9,696, depending on the specific hall. Learning communities aimed at students focused on the arts, the environment, or entrepreneurship, among other interests, come with additional fees.

Students living in non-university housing face highly variable costs in addition to tuition, says Susan Fischer ’73, ’79, director of the UW–Madison Office of Student Financial Aid. Rent for a two-bedroom apartment in the campus area averages $1,200 a month. “It’s crazy,” she says. “[But] that’s where students have an opportunity to economize. … You don’t have a chance to bargain tuition, but you do have a chance to live tight in other areas.”

The share of Americans who think a college education is important:

1978 – 35 percent

1985 – 65 percent

2014 – 70 percent

Source: Pew Research Center

During her own college days at the UW, Fischer recalls, she bought clothes at the Army-Navy surplus store because “looking like crap and living cheap was the hot thing to do.” Many of her former classmates from Madison West High School lived at home with their parents for the first two years to save money, and she never lived with fewer than four people. “There was an acceptance of living tight,” she says.

Nationally, about one-third of college students and their families pay the full sticker price for a college education without any financial assistance. The “net price” of attending the UW varies based on family income. In-state students from wealthier families paid almost the entire cost of attendance — including room and board, and other expenses — for the 2012–13 academic year. Those from Wisconsin families with incomes between $30,000 and $48,000 paid less than half of the cost, while those with family incomes of less than $30,000 a year paid a little over one-third of the costs.

A little more than half of UW undergraduate students complete applications for financial aid. There is $45 million a year in unmet need — the amount it would take to meet the full need of every student who applies — financial aid officials say. The state’s share of funding for need-based grants awarded at UW–Madison is lower today than it was a decade ago.

“We have parents who come in and just assume their full need will be met, but the fact that you have demonstrated financial need does not mean that there’s resources,” Fischer says.

Students who graduated in 2013 will need an average of 10 years to recoup the cost of their education, compared to 23 years for those who graduated in 1980.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Every student who applies for aid is considered for FASTrack, short for Financial Aid Security Track, which helps economically disadvantaged undergraduate students from Wisconsin pay for college through a combination of grants, work, and small loans. Students selected for the program are guaranteed that their demonstrated financial needs will be met for four years. FASTrack receives funding from the Madison Initiative for Undergraduates, which in 2009 began using $40 million a year in tuition funds to improve curriculum, create more opportunities to participate in research on campus, and make it easier to get into the courses needed to graduate in four years. Half of that money is committed to need-based aid, helping thousands of undergrads each year.

“For Wisconsin residents, I think it’s a myth that they can’t afford to be here,” Fischer says. “And I’m concerned that our lowest-income students self-select out before they even give us a chance to invite them into the FASTrack program.”

Tuition at Big Ten Public Universities

| University | Resident | Nonresident |

|---|---|---|

| Pennsylvania State University | $16,992 | $29,566 |

| University of Illinois | $15,258 | $29,640 |

| University of Minnesota | $13,555 | $19,805 |

| University of Michigan | $13,142 | $40,392 |

| Michigan State University | $12,863 | $33,750 |

| UW-Madison | $10,403 | $26,653 |

| Indiana University | $10,209 | $32,350 |

| Ohio State University | $10,037 | $25,757 |

| Purdue University | $9,992 | $28,794 |

| University of Iowa | $8,061 | $26,931 |

| University of Nebraska | $7,975 | $21,302 |

All public Big Ten universities assess additional fees for undergraduates enrolled in specific academic programs, such as engineering or business.

Source: Office of the Provost

Might tuition go up again?

In 2012–13, UW–Madison tuition and fees went up 7.4 percent compared to the previous year. It was the highest percentage increase among Big Ten schools, but about one-third of it was due to MIU. Now the UW’s tuition is at the midpoint of that peer group, after many years of being at or near the bottom.

Tuition has stayed the same since then — though fees have gone up — but a tuition freeze is not the simple solution it might appear to be.

- A “truth in tuition” policy for Illinois public universities, which took effect in 2004, locks in a rate for four years, but does nothing to control costs. Every four years, the entering freshman class must shoulder any tuition increases resulting from budget cuts, rather than sharing the pain with the rest of the student body.

- In Maryland, tuition went up only 47 percent between 2002–03 and 2012–13, thanks to a four-year freeze that began in 2007. After that, tuition increases were capped at 3 percent a year. The state has increased funding for higher education by 34 percent over the last eight years.

- More recently, the University of Minnesota struck a deal with its state legislature and governor to freeze tuition for two years — but it was paired with $42 million in increased state funding for the school.

The UW’s freeze covers tuition for all students, even though the board of regents could have charged nonresident undergrads — as well as graduate and professional (such as medical) students — more. Undergraduate resident tuition is governed by state statute, but the regents don’t need permission from the legislature to raise tuition for the other categories.

When the regents discussed the tuition freeze in June, regent Margaret Farrow shared her fear that an extension of the tuition freeze unnecessarily limits the UW System’s resources. “I think we should be raising nonresident tuition,” Farrow, a former state legislator, said at the time. “I think we are a bargain for nonresidents, and I wish they were paying more.”

Bazzell, the university’s top financial officer, says politics dictated that the freeze be imposed across the board for all categories of tuition, but adds, “There’s no question that the tuition pricing at Madison for professional schools — and, in many cases, for nonresident undergraduates — is low as compared to peers. And so the question is, is there an appetite at all to adjust tuition in some of these other categories?”

Chancellor Blank has been more blunt on the topic. “I see no reason why we should sell our education to out-of-state students cheaper than schools that quite honestly aren’t as good as we are,” she said during her State of the University speech last fall.

If the freeze on undergraduate resident tuition continues without additional state money to cover the cost of educating students, paying salaries and health care costs, and heating and cooling the campus, it seems inevitable that tuition for out-of-state students and those attending law school, medical school, and other graduate programs would go up to help fill the gap.

Bazzell says that if the regents and lawmakers consider tuition increases, it’s “imperative” for them to ask and answer a question: “Are we still accessible and affordable to a broad range of students? The economic circumstance an individual comes from shouldn’t be a limiting factor. Anytime we think about tuition increases, that proposition has to be central in our minds.

“It’s really a function of what the institution’s able to do to buy down the cost of education, so that low-income families can still afford the tuition pricing,” he adds. “And I think that’s still a challenge at Wisconsin.”

Going beyond freezing tuition, some who study higher-education access have proposed making college free.

At the UW, Sara Goldrick-Rab and Nancy Kendall, both professors of educational policy studies, have drafted a plan that would have the federal government cover tuition, fees, books, and supplies for the first two years of college. Students would receive a stipend and guaranteed employment at a living wage to cover their living expenses. “Financial aid does not necessarily lower the cost of attending college to the point that families can successfully manage those costs,” the professors wrote in a paper outlining their plan.

Earlier this year, Tennessee Governor Bill Haslam unveiled his plan to make the first two years of community or technical college free for high school graduates. His goal: increase the state’s percentage of college graduates from around 33 percent to 55 percent by 2025.

57 percent of Americans say higher education is not a good value, while 86 percent of college graduates say it was a good investment.

Source: Pew Research Center

Is college worth the cost?

College is expensive, but there is also a steep price to be paid for not earning a college degree — and that trend has increased over time. In the early 1980s, Americans with four-year college degrees made 64 percent more per hour on average than those without them. Today, that number has increased to 98 percent, according to U.S. Department of Labor statistics.

And despite the national conversation about the increasing cost of higher education, polls show that the majority of Americans — some 70 percent — still say that going to college is important.

Perhaps the work of MIT economist David Autor, published in Science, provides the most striking argument: the cost of a college degree is -$500,000 (that’s right, a negative number) because of the lifelong financial benefits it offers.

Bazzell notes that the 1950s, when his father earned his degree at the UW, was an era in which people could make a middle-class living with a high school education or less by working in a factory. “It was hard work, but you could enjoy a good lifestyle. Those jobs aren’t there anymore, and you really need some sort of postsecondary education to have an opportunity in today’s economy,” he says. “And so I find it concerning that we find ourselves at a time of great need in terms of the need to educate more of our citizens, but the opportunities are a lot more challenging these days.”

Jenny Price ’96 is senior writer for On Wisconsin.

Published in the Winter 2014 issue

Comments

Sara Goldrick-Rab (@saragoldrickrab) November 9, 2014

This article states that it is a “myth” that students cannot afford to attend UW-Madison. The facts are the following:

1. A student with no expected family contribution (e.g. the very lowest incomes) is left to borrow or come up with $13,794 per year to attend Madison. That’s after all grants & scholarships are applied. After doing work-study and agreeing to borrow $7,500 or more per year (for a total debt of at least $30,000 for the degree– likely more) that student still must contribute with almost $4,000 a year. This means that people from the poorest families must borrow to the max AND work in order to afford Madison. Is that “affordable” and does it meet with alumni expectations?

2. Low-income students already live quite frugally at Madison, as the Working Class Student Union members demonstrate. They are already using food stamps, shopping at second hand stores, forgoing books and other supplies, and often missing class due to work. Even so, we have students facing food and housing insecurity. We say it “doesn’t happen here” but it does.

Who is served by ignoring these facts? The article title “The Price is Right” reveals much.

At the Wisconsin HOPE Lab we’re striving to help colleges and universities find real “right” price to ensure that higher education levels inequality, rather than serving to simply reproduce it. See wihopelab.com

Scott November 20, 2014

With the newly found legislative preoccupation with divestment in funding for public schools, whilst directing public funds into private schools via vouchers: are schools looking into friendly trust funds (see movement of funds to tune of $50 mil by the diocese of Milwaukee in cemetery fund during bankruptcy proceedings) for more control over availability of resources so as not to allow legislative, psychologically conditioned agents of influence, the option of bankrupt public institutions?

Peter Horton December 2, 2014

The numbers you have from the Office of Student Financial Aid are for most students bogus. Most off campus living at the UW is 1/3 to 1/2 the cost of living in a dorm. Only the most luxury apartments in the downtown area cost a student more to live in than any dorm on the UW campus.

John December 13, 2014

The best explanatory factor for the rise of tuition is not mentioned in the article. It is the explosion in non-faculty professional positions. The American Association of University Professors has published a graph that sums it up nicely. Non-faculty professional positions have more than tripled, and so has tuition. Big business has taken over the big U.

http://bit.ly/1uRPTeA , which points to

http://www.aaup.org/sites/default/files/files/2014%20salary%20report/Figure%201.pdf

John December 13, 2014

[the blog ate my post, reposting]

There is one simple explanation for the threefold rise in college tuition, and that is the 369% increase in the number of “full-time nonfaculty professional” positions at universities. I can sum it up in two words: administrative bloat. The American Association of University Professors has a nice pdf graph that displays the statistics:

http://bit.ly/1uRPTeA

full URL http://www.aaup.org/sites/default/files/files/2014%20salary%20report/Figure%201.pdf

Andy January 13, 2015

The graph that John shared does not provide much information to jump to the conclusion that rising tuition is a result of bloated administration. For example, what is the difference between “Full-Time Nonfaculty Professional” and “Full-Time Non-TenureTrack Faculty”? It’s a known fact that more and more Universities including ours, are hiring academic staff lecturers rather then tenure track faculty to cut costs. I would think academic staff lecturers would fall into the category that you assume is all administration? I am also troubled by the mix in sources that was used to generate this graph and wonder if we are comparing apples to oranges? In our system, i believe all “faculty” are tenure-track. No academic staff members are considered faculty, thus the terms in the chart make no sense.

Matt January 13, 2015

John, Interesting and relevant point. Here is another article that points to a similar conclusion, although it isn’t simply administrators that have bumped up the cost, but also other support staff. They don’t give a clear reason why, but the need for computer labs and staff to keep them running might be part.

http://www.air.org/sites/default/files/downloads/report/DeltaCostAIR-Labor-Expensive-Higher-Education-Staffing-Brief-Feb2014.pdf

Matt

Jeff January 13, 2015

I’d like to know when the “once upon a time” period existed when you could earn enough just over breaks. Just for a reference point in time, here is my experience.

I feel fortunate to have attended when I did. I attended for five years 1994-99, worked two jobs between 20-40 hours a week during school time, and 40+ over every break. I commuted from the suburbs, living at my parents’ house. They provided no money, but the housing and food savings were huge. I got zero financial aid. I paid my tuition, books, car, insurance (and parking!) and everything else out of my pocket. Having a computer then was still kind of a luxury, I had to use the labs like most kids, and not living near them was a burden.

Living 12 miles off campus, I missed out on most of the “college experience”, and sometimes I’m envious of others that got to have that. I had to treat it like another job. But I managed to graduate debt free. If I had started just five years later in 1999 rather than 1994, I doubt I would have been able to do the same.

As for those commenting on administrative costs, absolutely the costs are higher. Today’s students demand wireless access everywhere, and ever sophisticated technology in the classroom. Keeping that technology infrastructure maintained costs an enormous amount, and there are many cascading support costs that start from there.

Grant January 13, 2015

To those who blame administrative bloat, I’d like to offer three observations:

1) I am told (but cannot personally verify) that administrative salaries currently constitute 3% of the total UW-Madison budget. If true, you could fire ALL administrators and not come close to covering the anticipated budget shortfall if we don’t receive either an increase in state support or the flexibility to raise tuition.

2) There are faculty and department chairs who believe that the administration in key campus offices is already understaffed to the point that the offices aren’t as effective as they should be.

3) Many of the new administrators hired in recent years have been hired in response to external mandates – e.g., compliance issues relating to federal grants, etc. The cost of not having someone overseeing compliance (e.g., due to fines or lost of funding) could easily be much greater than the cost of the administrators themselves.

Scott February 16, 2015

You could probably eliminate all “administrative bloat” and double the cost of tuition for out-of-state students and never cover the cost of a 13.5% cut in funding. So now what? Across the board tuition hikes, close down underutilized facilities. Maybe raise football and basketball ticket prices and route the increases to the library?