It Was a Very Good Year

In 1964, the campus experienced one of its most exciting years, with grand (and grandiose) expansion, and historic highlights in civil rights, science, and star performances.

Fifty years ago, the UW underwent one of the most pivotal periods since its founding in 1848.

University President Fred Harrington set the tone when he vowed in January that the university would “get bigger and better” that year. It certainly got bigger — 1964 brought the campus’s largest graduation, enrollment, and budget up to that time, a building boom that included the city’s tallest and the university’s biggest buildings, and plans to expand the campus in unimaginable ways.

The year grew even more notable as the months passed. Just before Thanksgiving, the UW community celebrated its extraordinary growth with a gesture of personal sacrifice. Some six thousand students — nearly a quarter of the student body — joined the National Student Association’s Fast for Freedom, skipping dinner and putting their money where their mouths weren’t, sending more than $5,000 (about $37,500 in 2014 purchasing power) to Mississippi to buy food for the poor, both whites and African Americans.

Campus interest in civil rights wasn’t due to demographics — there were more black students from Nigeria (23) than from Wisconsin (21), and among the 2,254 faculty, only nine were people of color. But all year, there had been an ongoing involvement in the primary political and moral issue of the day — the movement to end segregation in the South.

It had been just months earlier, in November 1963, when the Class of ’64 had its senior year rent by tragedy: the death of the president. But it bounced back. “Despite the lingering pall of JFK’s assassination,” then-Daily Cardinal editor Jeff Greenfield ’64 recalled in an email, “my overriding sense of 1964 was a sense of optimism.”

Students honored the late president by engaging in every form of civil rights engagement and by joining the Peace Corps in large numbers (especially after Bill Moyers, the organization’s deputy director and an assistant to President Johnson, came to campus to promote the Corps). The federal government returned the favor with unprecedented financial support, providing more than $57 million in the 1963–65 biennium, including $20.4 million in 1964 for research alone.

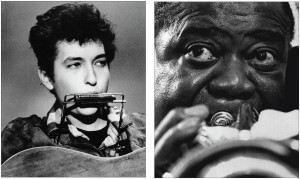

The sixties were in full swing, and the campus was swinging with them. Madison saw perhaps its greatest year ever for live music in 1964, featuring legends such as Bob Dylan, Louis Armstrong, Johnny Cash, the Beach Boys, the Four Seasons, and Roy Orbison. Violinist Isaac Stern, jazz pianist Oscar Peterson, and bluegrass pickers Flatt and Scruggs delighted diverse Union Theater audiences. Harry Belafonte headlined Homecoming, Bo Diddley rocked the Military Ball, and sitar master Ravi Shankar graced Great Hall — two years before Beatle George Harrison first heard him play.

At the beginning of the 1963–64 school year, students prepared to board a bus outside the Memorial Union, bound for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, where Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech helped to inspire continued civil rights activism. Photo: UW–Madison Archives 23/21 S00650

That spring, University Hospital became the first hospital to operate an IBM 1440 computer system — not for patient care, but for billing and other administrative services. And the UW became the first university in the country to put alumni transcripts (more than 350,000 of them) and all new student records on microfilm.

Howard Temin, assistant professor of oncology in the new eleven-story McArdle Memorial Laboratory for Cancer Research, announced breakthrough discoveries into the relationship between tumor viruses and cancer, the revolutionary “reverse transcriptase” analysis that would lead to his Nobel Prize in medicine in 1975.

Professor Lee Dreyfus, general manager of WHA-TV, organized a project televising reference books so that, as he told the Wisconsin State Journal, “500 students can read the same book at the same time.” Dreyfus, who went on to become governor of Wisconsin in 1979, also helped to demonstrate zoology instruction for faculty via television.

And much-anticipated construction on the Biotron, a unique facility to study living organisms under controlled environmental conditions, finally began.

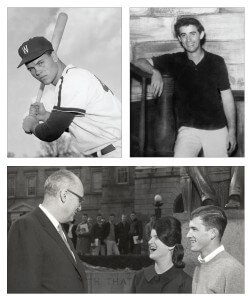

The campus also made national news for nonacademic reasons. A teenage courtship played out in January, when presidential daughter Luci Baines Johnson visited boyfriend Jack Olson x’68, a freshman from Maiden Rock, Wisconsin, and former congressional page. The two posed with Harrington before the Lincoln statue, had pizza at Paisan’s, and saw the Doris Day- James Garner romantic comedy Move Over, Darling.

And a homegrown Badger made national sports news with lasting impact when slugging baseball outfielder Rick Reichardt x’65, a junior from Stevens Point, signed with the Los Angeles Angels for an astronomical $200,000. The sum so shocked Major League Baseball that it started an amateur draft to stop the bidding wars for “bonus babies.”

Bob Dylan and Louis Armstrong were among the many big-name performers to visit Madison in 1964, along with Harry Belafonte, Bo Diddley, Johnny Cash, the Beach Boys, Flatt and Scruggs, Roy Orbison, the Four Seasons, Ravi Shankar, and violinist Isaac Stern. Photos: AP and AP/Eddie Adams.

The remarkable year was not lacking for campus high jinks, either. A spectacular frozen melee developed on the night of March 9, as students rolled a huge snowball, up to fifteen feet high, onto Observatory Drive just east of the new Natatorium, snarling traffic for a four-block area. As their number grew to about five hundred, the students tipped over two large flatbeds around the massive mound and pelted police with snowballs for about ninety minutes before they were rousted. There were no arrests.

Big, Big Red: the Badger Building Boom

Decisions made and actions taken in 1964 profoundly affected the UW’s physical presence.

“We have never had anything like the building program we now have,” Harrington told the regents in March. “I have been called a bigger imperialist than Theodore Roosevelt,” he added, referring to all the private homes and shops the university had purchased to allow the expansion.

It was 1964 that gave us the design for the university’s most massive structure, the $9.8 million South Lower Campus Building for History, Music, Art, and Art Education (now the George L. Mosse Humanities Building). But even as they approved the design, the regents had misgivings.

“Looks like something right out of Mesopotamia,” regent Charles Gelatt ’39, MA’39, MA’83 groused. Board president Arthur DeBardeleben said it looked like a factory. Engineering dean Kurt Wendt ’27, head of campus planning, promised that “a proper treatment would be developed to improve the appearance.” Plans for the adjoining Elvehjem Art Center (now the Chazen Museum of Art) also advanced, while private fundraising continued.

The regents also approved doubling the $5.5 million Language Building (now Van Hise Hall) to eighteen stories (making it the tallest building in Madison), along with plans for five natural-sciences buildings costing $17 million — all at one meeting.

The twin towers of Witte Hall opened that fall, with plans being drawn for another women’s dorm across Dayton Street. The dorm was never built, however, and that space is now occupied by the university’s “Taj Garage” parking ramp.

In 1964, the Administration Building, later named after business manager A.W. Peterson, was dedicated; Ogg Hall was under construction; contracts were let for Gordon Commons, and Union South was proposed. However, although diamonds may be forever, buildings are not. All of the structures have since been razed.

The Athletics Department scored in ’64, as the regents approved expanding Camp Randall with a 13,103-seat second deck and a two-story press box, building a Winter Sports Arena — and increasing ticket prices to pay for it all.

The decision to expand the stadium was not without debate. Gelatt warned of the “very real danger” that professional football “could drive college football off the air.” Regent Maurice Pasch wondered, “Has the athletic board given any consideration to the possibility of moving the stadium entirely?” DeBardeleben warned, “We should not take on commitments that for the next fifty years we are going to be bound to a good team,” and even questioned “whether this was a proper function of the university.”

Harrington assuaged the skeptics. “We have every expectation that the attendance will be above the 75 percent” needed to sustain the financing, he said. As to the winter facility, he offered that “curling would seem like a pleasant faculty sport.”

DeBardeleben was prescient. After the addition opened in 1966, the football team went 6 and 32 the rest of the decade, without a winning season until 1974.

The university also moved ahead with plans for a second gymnasium (now the Natatorium), apparently without concern for historic preservation. “We can’t tear down the old Red Gym,” Harrington said, “until we build a new one.”

Witte Hall opened in 1964 as campus administrators scrambled to prepare for the biggest enrollment in the university’s history. At the time, plans even called for the creation of a second four-year campus at the location of the current University Research Park on the west side of Madison. Photo: UW–Madison Archives S09037.

Staggering Number of Students

But the specter of an ever-increasing population on a campus about to burst was haunting the university.

Commencement that June set the tune, the largest of the 111 such events to date. As morning clouds cleared for a late spring sun, about 3,100 received degrees.

Enrollment in the spring of ’63 was 21,733, and 26,293 enrolled in the fall of 1964 — a 20 percent increase, the greatest two-year jump in the university’s history, before or since. And the state’s primary educational planning body, the Coordinating Committee on Higher Education (CCHE), said even more students were coming: 45,000 in 1970 and 52,183 in 1973, almost 20,000 more than any other plan had projected.

“The Madison campus figure is staggering!” Harrington exclaimed at the February regents meeting. Told that their campus population would double in nine years, administrators started planning to double the campus. There was regent agreement to hasten construction of student housing from 1,000 units per year to 2,500, including 3,000 new rooms, similar to the towering southeast dorms, on Observatory Drive across from the Natatorium.

Harrington had even grander plans — a complex of residential and academic facilities for 10,000 to 15,000 freshmen and sophomores near Picnic Point, and a similar setup north of the Veterans’ Administration hospital, now the site of the UW Hospitals and Clinics complex.

“The area at the base of Picnic Point is very promising,” Harrington said, although he admitted that there could be some “foundation problems as the land is below lake level.”

To cap it off, plans called for a four-year campus on the Charmany-Rieder Farms, on Mineral Point Road past Whitney Way, about five miles west of Bascom Hall. To Harrington, the only question was when a full western campus would open. “We will certainly have some sort of campus use here one day — very handsome and quite high,” he declared in September.

Not everyone jumped on the expansion bandwagon. “It was all madness — they had no sense of limits,” says Bill Kraus LLB’49, a respected insurance executive and political operative whom incoming Governor Warren Knowles would appoint to the CCHE in 1965.

But campus planners pursued their ambitions and even proposed a name for their concept. “We are talking about a nucleated campus,” Dean Wendt told the regents in March. Its purpose was to “cut down to a substantial degree the amount of student traffic.” The university was frantic to deal with the onslaught of automobiles, scooters, bikes, and pedestrians. “Drastic action is needed,” Wendt told the regents in January.

DeBardeleben was particularly ambitious, asking in April about “development of an underground rapid transit system” to serve the campus. Harrington said it would be cheaper to move the campus. DeBardeleben suggested a monorail “so that we can eliminate all parking problems.” Vice President Robert Clodius said they could look into one as had “been used at Disneyland and the World’s Fair.”

The administration even considered banning all student cars, Wendt said, but there was “some question about the legality” of such a move. The regents also reviewed, but did not adopt, a campus plan to post guards at three checkpoints to block all personal vehicles — including bicycles — during the workday.

Clockwise from top right: As a UW junior, Rick Reichardt made national sports news when he signed with the Los Angeles Angels for the unprecedented sum of $200,000. Former UW student Andrew Goodman was one of three Freedom Summer volunteers who were tortured and killed by the Ku Klux Klan in Mississippi. In January, Luci Baines Johnson, LBJ’s daughter, visited her boyfriend, Jack Olson, on campus, where they chatted with university president Fred Harrington, left, on Bascom Hill. Photos: UW–Madison Archives S09037, Wisconsin State Historical Society WHI-98263, UW-Madison Archives S04139.

University officials faced one big planning problem: nobody knew what future enrollment would be. “We have been consistently wrong in estimating what the numbers would turn out to be,” Wendt told the regents. “We anticipate that we might again be wrong.”

He was right — they’d be wrong. Enrollment hit 40,000 in 1979, eleven years after the CCHE said it would, and peaked (in 1985) at 45,050, well below projections.

Greeks had their own building boom as seven fraternities and sororities undertook additions or new construction, including the modernistic Sigma Chi house on Langdon Street. The fraternity left its historic site at the end of Lake Street to make way for a new Alumni House, which was originally to occupy the historic Washburn Observatory, but instead came to its lakefront location at the behest and bequest of the late Thomas E. Brittingham, Jr., a past Wisconsin Alumni Association president.

The Movement in Madison

But the biggest development affecting the letter societies wasn’t one of bricks and mortar, but of rights and privileges, as the faculty faced off with fraternities over their membership practices.

“Racial discrimination in the fraternity-sorority world,” broadcast journalist and author Greenfield says, was “the most polarizing topic” on campus.

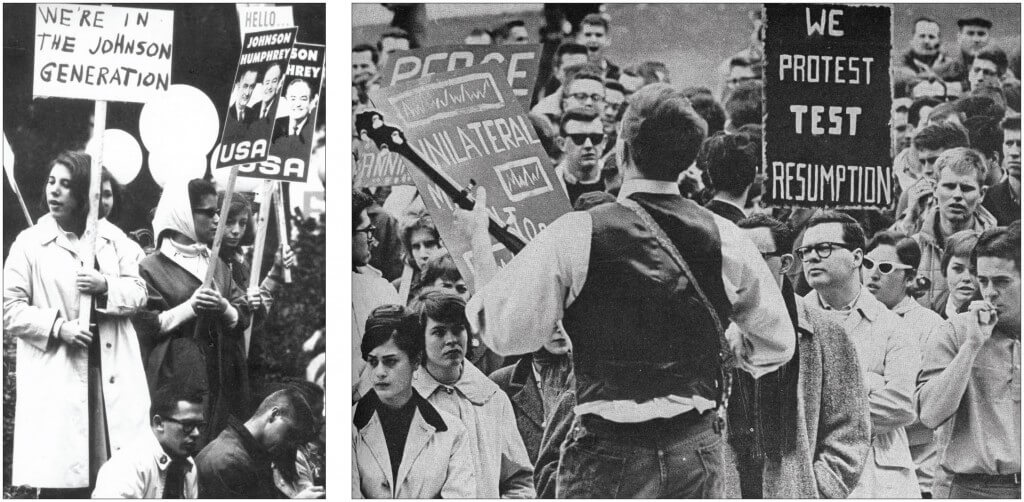

Although civil rights activism was not the all-consuming issue that the anti-war protest would soon become, it was the primary political cause on campus and off. Students formed the core of the Congress of Racial Equality cadre of volunteers, undertaking a series of direct actions that spring. They picketed and occupied the aisles of the Sears store on East Washington Avenue until the store hired a few black workers. They disrupted the State Assembly, bringing signs into the gallery and singing “We Shall Overcome,” and they chanted “Jim Crow Must Go!” when segregationist Governor George Wallace spoke to the Downtown Rotary club. And when several hundred northern students went to Mississippi for the historic Freedom Summer Project voter-registration effort, about twenty Badgers were on the buses.

Immediately afterward, new history grad students and civil rights activists Mimi Feingold Real MS’66, PhD’67, Vicki Gabriner MS’66, and Bob Gabriner MS’66 began assembling what has become one of the nation’s richest civil rights archives — the Wisconsin Historical Society’s collection of papers, records, and images concerning the Freedom Summer Project, with over 100,000 pages of primary source material. About a third of the collection has already been digitized and put online.

Although campus protests had not yet reached the fever pitch they would hit during the Vietnam demonstrations of the late sixties, there were still plenty of rallies revolving around issues such as politics, civil rights, and the burgeoning peace movement. Photos: UW-Madison Archives 23/11 S080270, S14040.

A Badger made national civil rights news in May when the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the disorderly conduct conviction of junior Dion Diamond, a prominent black activist from Louisiana who had recently transferred to the UW from Howard University. Diamond served his sixty days back home and returned to resume his activism and academics.

And there was a tragic Madison dateline when former classmates remembered Andrew Goodman x’65, one of three Freedom Summer volunteers murdered in Meridian, Mississippi. Goodman had come to the UW in 1961, but he withdrew for health reasons after a semester and transferred to Queens College (where musician Paul Simon became a friend). On June 21, Goodman, Michael Schwerner, and James Chaney were abducted, tortured, and killed by Ku Klux Klansmen. Their bodies were found in an earthen dam six weeks later.

The faculty weighed in on civil rights, insisting that alumni not be able to veto fraternity or sorority pledges for discriminatory reasons — although they could still weigh in on standards such as academics and character — and enacting a rule requiring all social organizations to certify that no constitution, bylaw, ritual, or rule required them to discriminate on account of race, color, creed, or national origin.

Most of the groups embraced the requirement and complied well before the November deadline. But challenging the rules as an improper intrusion into private affairs and alumni rights, Acacia and Phi Gamma Delta fraternities and Kappa Delta sorority refused to sign, and were recommended for termination. The Inter-Fraternity Association also took independent action, suspending Acacia from privileges. But all three later demonstrated sufficient compliance to maintain good standing.

Reality Check

Lastly, 1964 was an election year, filled with campus campaign appearances and protests — and a result that stunned the university: while Wisconsin voted 2–1 for President Johnson, it ousted incumbent Democratic Governor John Reynolds in favor of Republican Warren Knowles.

In December, Knowles denounced the UW’s “grandiose schemes” and warned of enrollment cuts and other austerity measures. “The people of Wisconsin are unwilling to pay higher taxes for state education,” Knowles declared. The university responded by submitting a record budget request, and waited for what cuts and caps might come.

At year’s end came a tantalizing tip about a future UW area of expansion. To “improve liaison between the university research people and with the industry people” and facilitate “research that will be helpful for Wisconsin industry,” Harrington reported in December, the university established a University-Industry Research Program. “We feel we have just begun,” he said. “There is a great deal more to do.”

In 1983, the regents would turn that nascent program into the 255-acre University Research Park, the R&D facility on the site of the Charmany-Rieder Farm — where fifty years ago, the university had planned to build its western campus.

A setback became a step forward.

Stu Levitan JD’86 is the host/producer of “Books & Beats” on Madison radio station 92.1, chair of the Madison Landmarks Commission, and author of Madison: The Illustrated Sesquicentennial History, Volume 1 (UW Press 2006).

Published in the Winter 2014 issue

Comments

Zach December 4, 2014

Question on the final paragraph: you say that the university had planned to build a western campus “fifty years ago” but the first year mentioned is 1983. Did you mean fifty years before 1983, or fifty years before *now* (2014), making it 1964?

Julie December 4, 2014

What a wonderful look at a different time here at UW-Madison – A legacy that has kept us all inspired.

Barbara jean December 6, 2014

In 1964 I was a 16 year old, working at the Memorial Union & thought the whole world was like my hometown, intriguing &interesting. While growing-up there, Madison had a Mayberry like quality, I’ve grown to love it’s split personality…

Dan December 6, 2014

Amazing…

History does repeat.

Monthly SEO Backlinks September 14, 2025

Why users still use to read news papers when in this

technological world everything is presented on net?