An Unsung Hero

Mildred Fish Harnack ’25, MA’26 lost her life in the German resistance to Hitler.

All the Frequent Troubles of Our Days tells the story of Mildred Fish Harnack ’25, MA’26, who met her German husband, Arvid Harnack MAx’26, while they were both graduate students at the University of Wisconsin. It recounts in riveting detail how Mildred went on to become a leader in the underground resistance to Hitler.

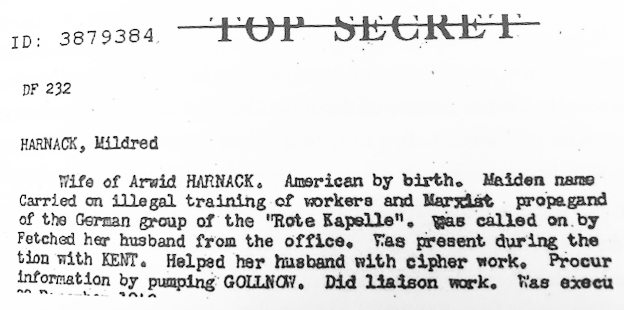

Mildred crossed the Atlantic and enrolled in a doctoral program in Germany when she was 26, just as Hitler was rising to power. Appalled by the Nazi leader’s popularity, Mildred and Arvid began holding meetings in their Berlin apartment to discuss strategies of opposition. During the 1930s, their small, scrappy group intersected with three other resistance groups. By 1940, it was the largest underground resistance network in Berlin. In 1942, the Gestapo tracked them down. Arvid was hanged and Mildred was beheaded, the only American woman executed on Hitler’s direct order.

Mildred’s great-grandniece Rebecca Donner conducted extensive research, drawing on family records and archival documents in four countries — Germany, England, Russia, and the United States — to create a compelling chronicle of courageous resistance. Mildred tried to thwart Hitler by every means possible, recruiting Germans into the resistance, producing and distributing anti-Nazi leaflets, helping Jews escape Germany, and becoming a spy in an effort to defeat one of the greatest evils of the 20th century.

Donner’s book, which she describes as a fusion of biography, espionage thriller, and scholarly detective story, has won numerous literary awards and is now out in paperback. We have excerpted a section that depicts Mildred and Arvid’s time at the UW and their move to Germany after their marriage.

From the book All the Frequent Troubles of Our Days by Rebecca Donner, published by Little, Brown & Company, an imprint of Hachette Books. Copyright © 2021 by Rebecca Donner.

IT IS SEPTEMBER 1, 1932.

In exactly seven years, the Second World War will begin.

This morning, by comparison, is not noteworthy. For Mildred it begins, we may imagine, like any other morning as she rises from a simple, wood-frame bed to draw back the curtains, letting in the light. Because the apartment has wide windows, there is plenty of it, even in the dead of winter, when the air in Berlin seems grainy, the texture and hue of chalk. A narrow hallway leads to the main room, where Mildred drifts from window to window, drawing back curtains. Bookcases crammed with well-loved books line the walls. Oil paintings of dense forests bring rich splashes of gold and emerald to an otherwise modestly furnished room. Here is a sofa with wooden armrests. Here are two tattered rugs. A sturdy round table, two sturdy chairs. Floor planks show their wear, pitted in places, and creak under Mildred’s feet as she moves to the far corner of the room, where a white porcelain stove stands, its thick pipe stretching to the ceiling. Sometimes there’s coal, sometimes there’s not. Today, perhaps, there is. Mildred stokes the coal lumps with an iron rod, bringing up fresh sparks. The water in the kettle she sets on the stove is enough for two cups of coffee, one for her, one for Arvid.

It’s by force of habit that she does this. She is alone, though not for long. Arvid will return from his trip to Russia soon, in time for her birthday. She will be 30 — is it possible? — in just over two weeks.

Breakfast is simple, usually nothing more than a hunk of bread swiped with whatever’s on hand — jam, butter, mustard, she’s not particular. At the center of the table, she likes to put a flower or two in a glass of water. Tulips in spring, lilacs in summer, alpine roses in the fall, honeysuckle in winter. Sometimes the flowers are from her students. Sometimes they’re from Arvid.

Arvid is a romantic. It’s a side others don’t see. Others see a man who wears round, owlish spectacles and rarely leaves the house without a necktie. (Behind closed doors, he happily yanks it off.) Others see a man who spends hours on end at his desk. (But Arvid loves nothing more than to amble around a mountain on a Sunday afternoon, letting his thoughts wander, inhaling the tart, bracing air.) And though it’s true that Arvid is a man who loves the certitude of cold, hard facts, his head is stuffed with poetry. He was made to read Goethe as a boy and can now, at 31, recite long verses from memory, murmuring them into her ear.

They met at the University of Wisconsin, when Arvid wandered into the wrong lecture hall. He’d wanted to watch Professor John Commons deliver a lecture on American labor unions, but the person at the lectern wasn’t Commons. It was Mildred, then a 25-year-old graduate student. The topic of her lecture was American literature, and he stayed until the end. Then he approached the lectern and introduced himself.

She’d gotten a BA in humanities and started her master’s. He had a law degree and was on his way to getting a PhD in philosophy. After these preliminaries were out of the way, Arvid told her — with a sweet, tenderhearted formality that pierced her to the core — that his family home was in Jena, a small university town along the Saale River in Germany. He spoke English awkwardly, though earnestly. How different he was from the Midwestern boys at the UW, boys who tackled each other in cornfields and on football fields, boys who bragged about all the money they’d make with their degrees, boys who vied for Mildred’s attention with boisterous jokes — Har-dee-har-har! — that weren’t at all funny, at least not to her, although you were supposed to smile anyway, smile and blush and flip your hand and say, Oh, you’re such an egg.

The second time they saw each other, Arvid brought her a fistful of wildflowers. He’d picked them himself. “A great bunch of thick, white odorous flowers mingled with purple bells,” Mildred wrote later, remembering every detail.

It was morning — a “beautiful” one. Arvid stood on the porch of the two-story house where Mildred rented a room. The house was near campus, owned by a professor who lived there with his wife and their two children. The wife peeked through the curtains, absorbing the sight of blue-eyed Arvid and his wildflowers. She’d taken a keen interest in Mildred’s private life. As Mildred worked doggedly on her master’s degree, the professor’s wife may have believed the younger woman could benefit from a little motherly guidance, mindful that the wrong man could lead her astray. Or maybe she was just nosy. At last she closed the curtains and nodded her frank approval. “Men from the North Sea,” she said, “make very good husbands.”

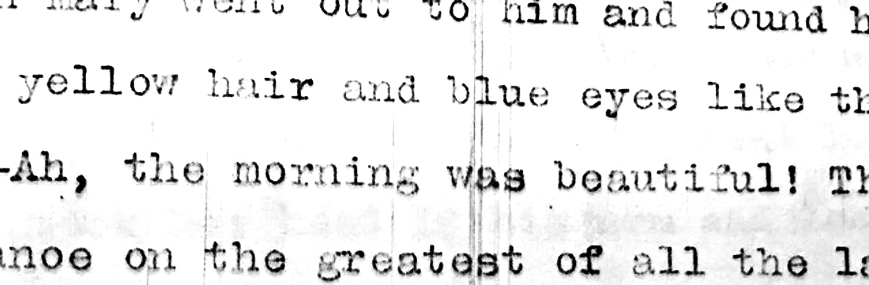

A husband — good or otherwise — was not what Mildred was looking for. Not now. She was still reeling from a heart-wrenching breakup with an anthropology major from Kansas City named Harry, but she stepped onto the porch anyway, shutting the door behind her. Arvid gave her the wildflowers and expressed his hope that Mildred was having a good morning. He labored to soften his German accent, and she realized that he’d practiced what he was about to say many times before coming to her door. He wanted to take her canoeing — on Lake Mendota, he said, “the greatest of all the lakes.”

His shy gallantry.

All right, she told him, with a shy smile of her own. She would join him in a canoe.

Six months later, on a Saturday, they said their vows under an improvised bower on a ramshackle dairy farm.

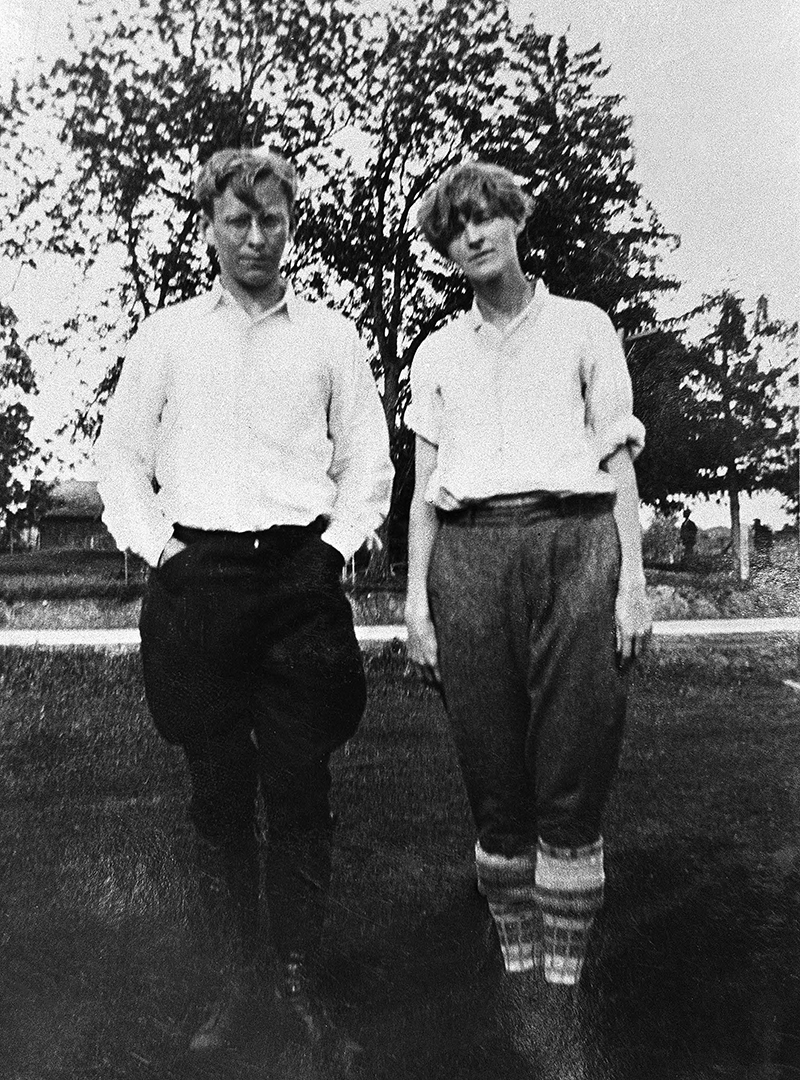

Arvid Harnack and Mildred Fish Harnack met on the UW campus and married soon afterward. They then moved to Germany, Arvid’s home country, just as Hitler was rising to power. Courtesy of the Donner family

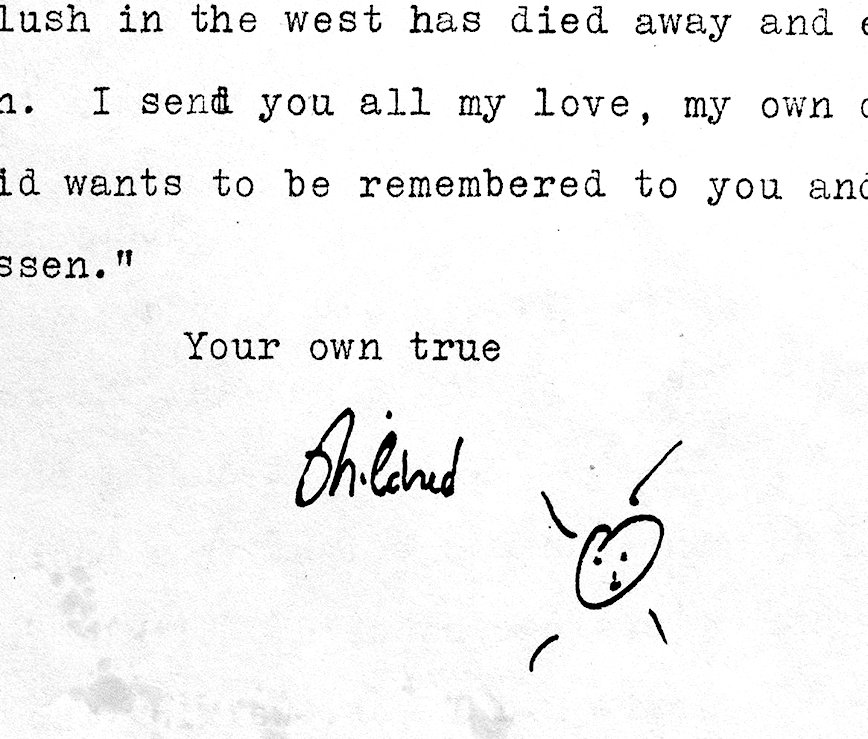

Arvid returned to Germany to finish his PhD. Mildred would join him soon; Goucher College in Baltimore had hired her to teach English literature for the 1928–29 term. While they were apart, they wrote long letters. They described the books they were reading, their plans for the future. They would both become professors and teach in German universities, and perhaps American universities too. Mildred ended her letters with a drawing of a sun. Arvid ended his letters with the same sun.

THERE ARE MOMENTS — this morning may be one of them — when she misses Arvid with a force that takes her breath away. Right now, he’s probably eating breakfast too, seated at a table in Moscow with a group whose very name is a mouthful: Arbeitsgemeinschaft zum Studium der sowjetischen Planwirtschaft, or Working Group for the Study of the Soviet Planned Economy. (Mildred prefers to refer to the group by its less cumbersome acronym, ARPLAN.) Its members include economists, political scientists, literary critics, politicians, and playwrights, among them self-avowed right-wing ultranationalists and die-hard Communists. In other circumstances, these strange bedfellows might not have shaken hands, much less sat around a breakfast table, but Arvid is optimistic; they may disagree about methodology, but they are united in their aim.

Germany is in crisis. Something must be done. By studying what appears to be a novel economic solution to the Soviet Union’s woes, Arvid hopes to discover a remedy for the crisis in his own country. Arvid is secretary of ARPLAN. He receives no pay for this work, but his compassion for the poor in Germany and his desire to devise a new economic model to address this problem drive him to his desk day and night.

There are two desks in the apartment. Arvid’s is a great expanse of carved wood that once belonged to his father. The other desk, equally imposing, was once his maternal grandfather’s — Arvid calls him Grossvater Reichau. This is Mildred’s desk now. A big slab of mahogany. Lectures, articles, translations — she writes them all in longhand, filling page after page before turning to the typewriter.

It’s here, at Grossvater Reichau’s great slab of a desk, that Mildred stokes her own outsize dreams. One day she will be a great literary scholar; she will write magnificent books. The desk imparts heft and weight and stability, qualities that are entirely foreign to Mildred. She has no family heirlooms of her own. Whatever slim sticks of furniture had cluttered the small, drafty rooms of her childhood she has long since left behind.

MILDRED DOESN’T LINGER LONG over breakfast. A final swallow of coffee and she’s on her feet again, setting the cup and saucer in the sink, brushing crumbs from her lips. Dirty dishes will accumulate there for days before she notices them, a teetering tower of plates and cups and cutlery. There are always better things to do than the dishes.

She’s still wearing a bathrobe over her nightgown and long, boiled-wool stockings knit by her mother, who bundled them up in a trim package that took two months to make its way from a transatlantic steamer ship to her front door. Her feet skim the creaking floorboards — the heel of one stocking is wearing thin — as she walks to a wide window and opens it. The air, crisp as a cold apple, invigorates her. She flings off her bathrobe.

She begins a series of exercises now, following directions from a book she bought for a few pfennigs. “Most of the exercises aim to strengthen the muscles of the abdomen,” she wrote to her mother last year, scribbling a hasty assurance that she and Arvid will have children “as soon as we can.” The routine — leg lifts and sit-ups and backbends — takes 20 minutes. She’s slender as a dancer, but she’s more earnest than graceful as she flails her arms, kicks her legs. Her nightgown bunches. Her stockinged feet on the wood floor skid and slip.

After exercising, she bathes quickly, using lard soap, and gets dressed.

Though today isn’t significant in the grand stretch of history, to Mildred it’s an important milestone. Today she begins a new teaching job at the Berliner Städtisches Abendgymnasium für Erwachsene — the Berlin Night School for Adults — nicknamed the BAG. There, she’ll come into contact with a fresh crop of German students, and she’s energized by the possibilities. They will be different from the students she taught at the University of Berlin — poorer, predominantly working class, mostly unemployed. Precisely the type of person the Nazi Party has been relentlessly targeting with propaganda.

See her now, striding out the front door with her leather satchel, descending four flights of stairs to the sidewalk. See her walking toward the U-Bahn station, swinging the satchel. In the eyes of her neighbors, she’s an American graduate student, nothing more. •

The rest of the book describes the couple’s resistance work in suspenseful detail, as well as documenting their tragic capture and death.

Published in the Fall 2022 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.