DARE to Be Done

Dictionary of regional dialects nears completion.

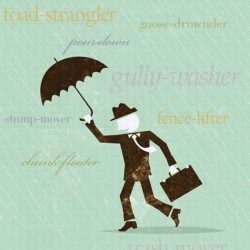

Meandering its merry way through new submissions such as whiffle-minded, whistle punk, and williwags, the Dictionary of American Regional English (DARE) project is nearing completion on a mission more than four decades in the making.

DARE, hailed as a pinnacle of American lexicography, received a two-year, $295,000 boost from the National Science Foundation (NSF) this year that will help close the book on its fifth volume — covering Si through Z — and lead the project into a second life as a digital, online resource.

In DARE parlance, you might say the project is “over the dog and will get over the tail, too.”

Old school: Although UW staff have been working on DARE for four and a half decades, some procedures remain unchanged, such as cataloguing words on note cards. At left, DARE founder Frederic Cassidy pores over his cards; at right, today’s editor, Joan Hall, does the same. Photos: Jeff Miller

“It’s very exciting, but it doesn’t feel like the end,” says Joan Hall, chief editor of DARE, part of the Department of English. Hall notes that a sixth volume of supplementary data is in the offing, and the online version of DARE will provide a platform for continual expansion.

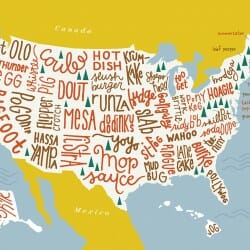

DARE is a reference tool meant to capture not the homogenous whole of English found in conventional dictionaries, but the rich, regional variety spoken across America. One NSF reviewer put it this way: “From its inception, this project took seriously the principle that a language is, in fact, the sum of its parts, and its parts are dialects.”

The project began in 1965 as the brainchild of Frederic Cassidy, who served as chief editor of DARE until his death in 2000. Cassidy led extensive fieldwork from 1965 to 1970 across the country, capturing through surveys and audio recordings a vast wealth of first-person detail on language variation. Those field findings have always been supported by print materials, but are now hugely supplemented by digital collections.

The dictionary has attracted some high-profile friends over the years, including nationally syndicated columnists William Safire and James J. Kilpatrick. During a financially tough period for the dictionary, Hall recalls that one of Kilpatrick’s “Writer’s Art” columns about DARE concluded with this: “For any person who loves the English language and revels in its richness of idiom and word origin, [DARE] offers a cause worth supporting. … If you can’t send a million, send something.”

More astonishing is DARE’s use in solving crime. Forensic linguist Roger Shuy, working on the Unabomber case in the 1990s, employed DARE to develop a complete cultural, religious, and educational profile of the suspect, based on his voluminous manifesto. The profile proved to closely resemble the man eventually convicted, Ted Kaczynski.

In another case, Shuy helped solve a kidnapping and extortion case by using DARE. A child was abducted from her home, and a scrawled ransom note was left behind demanding $10,000. The letter read, in part: “Put (the money) in the green trash kan on the devil strip at the corner of 18th and Carlson. Don’t bring anybody along. No kops!”

Hall says that Shuy discerned a lot from the note, including that the “c” words were deliberately spelled with a “k” to suggest a lack of education. But the real kicker was “devil strip.” According to DARE, that phrase describes “the strip of grass between the sidewalk and the street,” known in Madison as a terrace. Hall says “devil strip” is used almost exclusively in a well-defined triangle in Ohio between Youngstown, Cleveland, and Akron. This piece of evidence helped build a case against one suspect, who later confessed to the crime.

The new NSF grant now represents more than two decades of continuous support from the federal agency. DARE also relies upon core funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities, gifts from private foundations, and donations from individuals.

For regional English buffs, here’s more on the first three terms in this story. “Whiffle-minded” is a Maine term for vacillating; a “whistle punk” is a Pacific Northwest logging term for a person who controls the whistle on a donkey engine; and “williwags” is a New England term for tangled underbrush.

Published in the Summer 2009 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.