A Worldly Taste for Cheese

I love cheese. It’s been my number-one food group for years, so as a student I loved working at Babcock Hall, where I was, at any given time, fewer than twenty feet from at least ten types of cheese.

When I moved to Kenya, and then to northern Uganda, I knew my lifestyle would change. No sit-down toilets where I lived? Whatever. No steady electricity? Child’s play. No easy access to cheese? Now, that was genuinely difficult. During my six months in Uganda, I ate cheese a total of six times. I usually consumed six ounces by 10 a.m. back in the States.

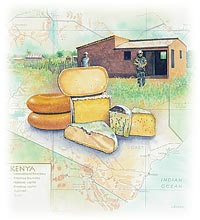

So when I stopped in at the Dorino Lessos Creameries Cheese Factory in Eldoret in western Kenya, on my way to Nairobi, I was in heaven. The factory is tucked away on the outskirts of town, behind trucks in a construction yard and next to a car wash, which consisted of buckets of water and soap. Once I arrived at the factory, an unassuming building with a green-and-white painted sign, I thought it was glorious.

For the residents I talked with, the factory is a welcome constant. Eldoret, a bustling town of 200,000 nestled in the jagged and beautiful Rift Valley, is known for its talented runners. It’s also the birthplace of Kenya’s second president and was terrorized following disputed elections held in 2007. By late January 2008, more than 1,500 people had been killed during post-election violence, and Eldoret had been the epicenter of much of it. The town, locals told me, was dead, in every sense of the word.

Yet Dorino Lessos hired a local security team and remained open, explained Nixon Kebeya, the factory’s manager, who told me that he’d heard of Wisconsin’s famous cheese curds. He said it was essential that the factory stay open, providing a friendly culture and a sense of familiarity — not unlike the Babcock Hall Dairy Store, where regular customers line up for ice cream.

My visit to Dorino Lessos put my yearning for cheese in perspective. And I made a friend. After my tour of the actual factory — a room about the size of the Memorial Union’s Rathskeller with machines from 1965 that still get the job done — I went over to the register to do some taste-testing. There I met Grace Arita, who was buying milk and cheese. I asked her what she thought of the factory.

“It’s the best,” she said, as we high-fived to celebrate our mutual adoration of Cheddar.

Minutes later, as I was concluding my tour of the factory, which receives twenty thousand liters of milk from local Kenyan and European farmers each day, I approached Arita again and asked what else I could do in Eldoret.

“You come home with me,” she answered, and that’s how I spent the rest of my day. I sat in the back of a sedan as Grace and her husband, Charles, took me to their home seven kilometers outside of Eldoret. As we drove, they talked about the “Gateway to Violence,” the road to their house on the outskirts of town that had been blocked by rioters. They showed me charred, black buildings adorning a hilly, green backdrop. Across from their house stood a field where groups had congregated with arrows and machetes. That’s when they fled, they said, spending three weeks with a family friend. They returned, but had to leave again seven days later when a political figure was killed and the violence flared up again.

“You see it in newspapers, but when it happens to you, it’s different. You’re shocked,” Charles said.

I, too, was shocked. Although six months had passed since violence overtook Eldoret, clear evidence — both physical and emotional — remained. Yet Kenyans are resilient; as we arrived home, the Aritas and one of their three sons assured me that Eldoret was back to normal. For one of the first times since I’d been in East Africa, I experienced a typical family environment. I watched The Little Mermaid with their son, took a welcome shower (my hotel didn’t have running water), ate fresh avocado, and drank Kenya’s typical tea, which was mixed with the milk Grace Arita had bought a few hours earlier. We bonded, and now I have great friends in Eldoret, all thanks to my visit to Dorino Lessos.

For an area people commonly associate with earlier violence, my memories are of a neighborly culture, warm people, and cheese.

Thumbs up to Eldoret and its people. And, hey — a big high-five for cheese.

During 2007 and 2008, Laura-Claire Corson ’07, former managing editor of the Daily Cardinal, volunteered with an HIV-positive orphanage in Kenya and for a non-governmental organization in northern Uganda that tests for and counsels people about HIV.

If you’re a UW-Madison alumna or alumnus and you’d like the editors to consider an essay of this length for publication in On Wisconsin, please send it to onwisconsin@uwalumni.com.

Published in the Fall 2009 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.