Behind the Scenes on Capitol Hill

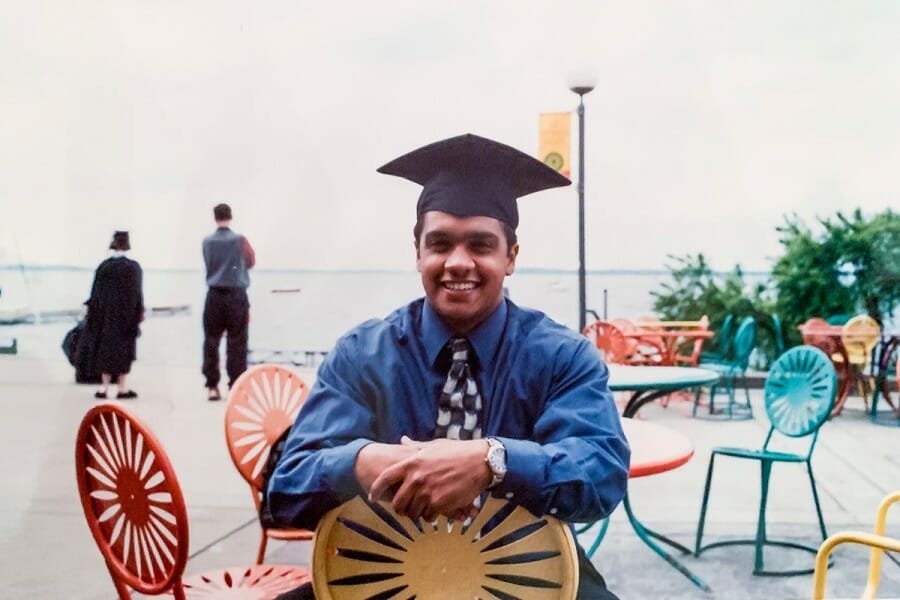

Manu Raju ’02 rises to CNN’s chief congressional correspondent at a turbulent time for politics and media.

“I’m seeing dozens and dozens of police officers in riot gear, wearing gas masks. And I can tell you it smells like tear gas. … As I’m walking through the tunnels here, there’s debris everywhere. The rioters clearly have breached all elements of the building.”

Manu Raju ’02 is on live television, audibly out of breath, as he’s being escorted alongside other members of the press corps by Capitol Police to a secure and undisclosed location. It’s January 6, 2021, and one sign that something surreal is happening is the slightly shaken voice of a normally composed CNN reporter. He knew it was serious when he received an email from police three hours earlier with an “internal security threat” warning and directions to lock down and remain quiet.

Raju, 41, had arrived at the U.S. Capitol to cover the certification of electoral college votes in Joe Biden’s victory over Donald Trump for the presidency. What’s typically a formality turned into a deadly affair when a violent mob of Trump supporters rushed the building and interrupted the proceedings. Throughout it all, Raju did what he does every day on Capitol Hill: talked to sources and reported breaking news on TV, Twitter, and CNN’s website.

“It was so chaotic, and people were glued to their phones,” Raju says. “A lot of people in the Capitol told me that they were relying on my tweets. They didn’t have the TV on because they were hiding under their desks, or they were in shelter, and they did not want to draw attention. We pushed out as much information as we could.”

He adds: “I reflect back on that day, and I often think that I had no idea how much danger we were in.”

Raju, whom CNN promoted to chief congressional correspondent in January, has covered politics in Washington for nearly 20 years. He’s reported on presidential impeachment trials, Supreme Court nominations, key Senate races, and government shutdowns. He also tracks the obscure machinations of an increasingly contentious Congress — a flood of motions and amendments, committee hearings and legislative debates, filibusters and vote-a-ramas. To stay on top of it all requires remarkable skill and stamina.

The job also requires thick skin. A president famously labeled Raju’s network “fake news” and even “the enemy of the people”; a senator insulted him in the halls of Congress. On January 6, a haunting phrase was carved on a door of the Capitol: “Murder the media.”

But Raju has always stayed above the fray, which has earned him widespread trust and admiration from colleagues, politicians, and sources of all stripes on Capitol Hill.

“He is indefatigable,” says Sam Feist, CNN’s Washington bureau chief. “And this may sound cliché because people talk about hardworking reporters, but he really is the hardest-working reporter on Capitol Hill. And I think that almost everybody who knows him will agree.”

Raju’s meteoric rise in Washington — from a rookie policy insider to one of the nation’s most visible reporters — traces back to an unconventional start at UW–Madison.

An Unusual Beat

Raju works for a 24/7 news operation, and his routine reflects it. “My day starts the moment I wake up,” he says.

He begins answering emails around 6 a.m. There’s an eight o’clock conference call with his news team, and he joins a larger editorial meeting at nine. By the time he arrives at the Capitol and checks the schedule for the Senate and House of Representatives, he’s developed a plan — “a roadmap in my mind,” he says — for the stories he wants to cover and the sources he needs to interview.

At times, the mapping is literal. Raju could make a detective blush with his ability to track the movements of members of Congress, learning their preferred routes from offices to committee hearing rooms to legislative chambers. If he intercepts them — and if they’re willing to talk, which is never a given — he only has a few minutes to extract something newsworthy. “You need to be prepared,” he says, referring to not only the questions but also the fact that he may need to ask them at a near jog.

“Covering Capitol Hill is an unusual reporting beat,” says Feist, who oversees Raju’s work. “You don’t sit at a desk like you might at the White House or the Pentagon, and you don’t sit in a newsroom. You literally work the halls of Congress, and he does that better than anybody.”

In 2017, Raju’s hallway interview with Bob Corker dominated a news cycle and sparked a war of words between the former Tennessee senator and President Trump. “When [Trump’s] term is over, I think the debasing of our nation, the constant non-truth-telling, just the name-calling … will be what he’ll be remembered most for,” Corker said. The six-minute interview marked one of the first public fractures between Trump and a Republican member of Congress.

“Some people see that kind of reporting as performative, but I do not,” says Kathleen Bartzen Culver ’88, MA’92, PhD’99, the James E. Burgess Chair in Journalism Ethics at UW–Madison. “Trying to get statements from politicians in the moment is a critically important part of congressional reporting, because otherwise, we’d be left with canned statements during hearings and in press releases.”

When Raju gathers a new piece of information, he sends a quick note to the network. If it’s important enough, he’ll be asked to report it on air immediately and field questions from CNN’s news anchors. He shares many of the same scoops on Twitter and holds other information for online stories.

His personal rule for sharing news across platforms is consistency. Some political reporters let loose on social media, but Raju’s Twitter feed is one unending string of straight reporting. You’ll find neither personal commentary nor cat photos.

“I don’t say anything on Twitter that I would not say on TV or I would not report online,” he says. While the approach isn’t sexy, it’s earned him a massive reach — more than half a million followers on Twitter alone.

With his thoughtful reporting, Raju has developed a thick Rolodex of sources, ranging from aides to politicians themselves. The key, he says, is maintaining their trust.

“The big thing is to never surprise them,” he adds. “When there’s a story that may reflect poorly on them or their bosses, you have to tell them ahead of time and give them enough time to respond before you report it.”

His relationship with sources allowed him to report with certainty on January 22 — three weeks before the eventual vote — that there wouldn’t be enough Republican support to convict President Trump on the latest article of impeachment.

“At the time,” he says, “people were looking at me, saying, ‘Are we leaning too hard into this?’ And I was like, ‘I’m telling you, I’ve spoken to everybody — nothing is going to change here.’ ” He was right.

Raju’s workday doesn’t end until the work of Congress ends. And during marathon events like an impeachment trial or the deliberation on landmark legislation, that means he doesn’t leave the Capitol until late at night or early the next morning.

“What keeps me motivated is the desire to tell people something they don’t know,” he says. It’s a journalistic urge that he discovered at the UW — while studying business.

“What keeps me motivated is the desire to tell people something they don’t know.”

An Unconventional Path

Raju is the son of Indian immigrants. His grandfather, Gopalakrishna Adiga, was a pioneer of modernist poetry in India. Raju’s family compares his work, in the native language of Kannada, to that of T. S. Eliot’s in the West.

Raju grew up in Darien, a small suburb of Chicago, where his father worked as a doctor at the University of Illinois–Chicago Hospital. “Growing up with a family of immigrant parents, they really instill in you hard work and work ethic,” he says. “They were never fully satisfied.” But they let Raju and his older brother pursue whichever careers most interested them. For a young Raju, and for no particular reason, it was business.

Raju chose to attend the UW after a stroll through campus. When he discusses his college years, the solemn tone of a TV newsman fades and a warm, lighthearted, humble personality emerges.

His older brother covered sports for a college newspaper at the University of Michigan, so Raju decided to do the same, just for fun. He applied to the Badger Herald, and the sports editor, Dan Alter ’99, assigned him to cover men’s hockey practice the next day. After a few quick pointers from Alter (including to always carry two pens), the future TV news star finished his first story. “I really had no idea what I was doing,” Raju recalled in an essay after he won a Forward under 40 Award from the Wisconsin Alumni Association in 2018.

During his time on campus, Raju worked for student radio station WSUM and became more involved at the Badger Herald. He rose to be the paper’s sports editor during the glory years of Wisconsin men’s athletics — two Rose Bowl victories and a Final Four appearance in basketball. He landed a summer internship with NBC in Los Angeles and later NBC15 in Madison.

By the time he graduated from the UW, Raju knew that he wanted to pursue journalism despite his degree in business administration. But his foray into politics — much like his introduction to journalism — was largely happenstance.

A Rise through Washington

Raju’s parents had moved to Washington, DC, while he was in college. When he graduated, he decided to move in with them and search for jobs in the area.

He caught his first break covering pollution control for Inside EPA, a trade publication for environmental policy wonks. (One report: “EPA Review of Flame Retardant Risks Will Affect U.S. Stance on EU Ban.”) A few years later, he started to write for Congressional Quarterly on the energy beat, where he first cultivated sources on Capitol Hill.

Raju could deftly translate technical policy into understandable terms. The Hill newspaper recognized his skill and hired him in 2007 as a Senate reporter. A year later, he left for a national audience at the all-digital Politico, where he wrote for seven years and became an award-winning senior congressional reporter. His versatility across media platforms and range in policy and politics opened doors at CNN.

While at Politico, Raju was frequently booked by CNN for guest appearances. “It was very clear, even then, that Manu Raju was one of the best correspondents covering Capitol Hill,” Feist says. “When we had an opportunity to hire a congressional correspondent, he was at the top of our list.”

After Raju joined the network in 2015, he was soon met with one of his biggest challenges yet: a public distrust of national media.

A “Fake News” World

A tried-and-true tenet of journalism is not becoming part of the story. In January 2020, Raju couldn’t avoid it.

During a routine hallway interview, he asked then–Arizona senator Martha McSally whether the Senate should consider new evidence that arose during the first Trump impeachment trial. She snapped: “Manu, you’re a liberal hack, and I’m not talking to you.” The interaction was caught on camera and exploded on social media. McSally promptly fundraised off the incident and sold “liberal hack” shirts.

Raju’s colleagues and competitors rallied to his defense. Geraldo Rivera defended him on Fox News. MSNBC’s Lawrence O’Donnell wrote on Twitter, “I’ve never see[n] a senator treat a reporter like this. Manu Raju is one of the best congressional reporters I’ve ever seen, including my years working in the Senate. I’ve never detected a hint of liberalism or partisanship from [him].”

Raju handled the incident with typical aplomb. “The people who are coming after us and calling us names are trying to influence how we report the news,” he says. “But my philosophy is to ignore it, endure it, and report factually based on what we know.”

Feist says Raju was simply doing his job — asking tough questions of those in power. “Manu is about as apolitical a person as I know,” Feist says. “He doesn’t pick sides.” That was true when Raju asked Representative Ilhan Omar, a Democrat from Minnesota, about her and President Trump accusing each other of hate. “Are you serious?” she responded. “What is wrong with you?”

Politicians attacking journalists is a trend that concerns Culver, who serves as director of the UW’s Center for Journalism Ethics. “Manu Raju is trying to represent the public interest and hold people accountable,” she says. “And anyone who wants to subvert that and call him an enemy of the people or a liberal hack — I’d like to know what their replacement system is. The news media are a systemic check on government power in this country. If you don’t want someone like him doing his job with care and consideration, then how is the public represented?”

Many polls suggest that trust in national media is at an all-time low. Last year, a Gallup poll found that 60 percent of Americans have little to no trust in mass media to report the news “fully, fairly, and accurately.” A Pew Research poll found that CNN is trusted by 70 percent of liberal Democrats but only 16 percent of conservative Republicans.

Culver notes that distrust in cable news networks likely stems from their increasing reliance on pundits to fill around-the-clock airtime. Viewers may struggle to separate opinion coverage from the news operation.

She also points to the “hostile media phenomenon.” Researchers have found that even when they create a perfectly neutral news text (affording equal prominence to conservative and liberal sources), partisans view it as biased against their views.

“So you could be the ideal neutral news reporter — much like Manu, who does not bring a lot of emotion into his interviews and is very straightforward — and people will still see you as hostile to their views,” Culver says. “What’s important for us as citizens in a democracy is to focus less on whether an outlet is biased against what I think and instead ask, ‘When was the last time I opened my mind about what I think?’ ”

The Next Story

Raju considers himself a family man. Aside from following Chicago and Badger sports, he dedicates nearly all of his off hours to raising five-year-old twins with his wife, Archana, who serves as vice president of marketing and business strategy at a national cloud and data center company. When he’s not covering an all-encompassing event, he spends the entire weekend with them.

Other than that, he says, “I’m always working on and thinking about the next story.”

Madison is never far from his mind. If you’ve watched CNN over the past year, you’ve likely spotted a red Terrace chair in the backdrop of his at-home interview setup. His Twitter bio concludes with the phrase Wisconsin Badger for life.

“There’s no question if it weren’t for my time there, I would not be where I am today,” he says. “I love the University of Wisconsin. It’s like home to me. I love Madison. There’s really no other place I’d rather be.”

For now, Madison will have to remain his home away from home. There’s much more work to be done in Washington.

“The good thing about being at a place like CNN is that it’s a huge network with lots of opportunity to grow,” Raju says. “But I’m happy with what I’m doing now, so we’ll just see what happens in a few more years.”

He pauses for a few seconds — notable only because he so rarely does it.

“If I can survive this pace.” •

Preston Schmitt ’14 is a staff writer for On Wisconsin.

Published in the Summer 2021 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.