Been There, Done That

A two-time winner of the Pulitzer Prize shares lessons from the front lines.

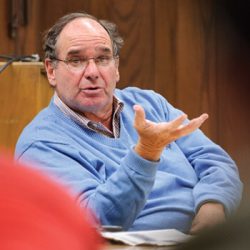

People … want to tell you the story,” reporter Anthony Shadid told journalism students when describing his experiences covering war-torn countries. Photo: Bryce Richter

You could have called it a master class when a dozen UW–Madison journalism students experienced an up-close-and-personal session with Anthony Shadid ’90 last fall. Little did they — or he — know that he’d soon have more harrowing tales to tell. Just a few months later, while reporting for the New York Times, he was captured and held for six days in Libya until Turkish diplomats arranged for his release, along with photojournalist Lynsey Addario ’95, and two Times colleagues.

But before students could get too intimidated in class that day, Shadid — who has twice won a Pulitzer Prize for his reporting on the war in Iraq — reminded them that he started his career just down the hall at the Daily Cardinal, where he worked as campus news editor while earning a degree with majors in journalism and political science.

“I always get a little nostalgic when I come back to Madison,” said Shadid, deputy bureau chief for the New York Times in Beirut, who most recently covered the uprisings in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya.

Journalism Professor Stephen J.A. Ward, director of the Center for Journalism Ethics, brought Shadid to campus for a public lecture on the Iraq war. But before he addressed about three hundred people attending his talk, Shadid met with students in J666: Professional Responsibility in Mass Communication.

The class picked the brain of a reporter who has spent the last eight years covering conflict in the Middle East.

Iraq is a “devastated place,” he said. “You cannot meet one person in Baghdad who hasn’t had a friend or relative killed.”

Shadid started studying Arabic while attending the UW, and he continued when he went abroad at age twenty-five. Knowing the language has been key to reporting beneath the surface of what governments reveal, he said, responding to a student’s question about how he finds sources that others don’t.

“Language is a prerequisite if you have any hope of getting deeper in the story,” he answered. “Interviewing is a question of trust, and language is a part of that.”

Time is another factor. Shadid recounted spending eight days with Iraqi parents who were trying to find the body of their dead son. His observations filled five notebooks. “What I find in conflicts is that people want to bear witness, and they want to tell you the story,” he said. “What we do is worthwhile when we do that.”

But, he acknowledged, his job also is dangerous. When he started working as a Middle East correspondent for the Associated Press in Cairo in 1995, reporters were regarded as noncombatants. That has changed: Shadid was shot in the back of his shoulder while covering fighting in the West Bank city of Ramallah in March 2002. Then came his capture in Libya, when he heard soldiers shout “Shoot them!” in Arabic, and, he says, “we all thought it was over.”

“How do you deal with fear?” asked Ward, who was a war correspondent in Bosnia, during the class.

“I think there are stories worth getting hurt for,” Shadid said. “I didn’t enjoy getting shot in the back, but I think that story was worth telling.”

Shadid also warned students about the pitfalls of getting too close to sources, something that can happen in a foreign post, where relationships between reporters and government officials become very informal.

“Have you developed a pretty good sense, when you’re interviewing someone, of when they’re trying to manipulate you?” asked Tim Oleson, a first-year graduate student. Shadid said people push agendas that don’t match reality, but noted that some reporters in Iraq have the advantage of having been there longer than some U.S. officials.

“I’d rather do street reporting than talk to people at the embassy any day,” he said.

Kyle Mianulli x’11, managing editor of the Badger Herald, asked Shadid if there is one story he wishes he would have reported.

“Absolutely. Abu Ghraib,” Shadid said.

When he was reporting in Anbar province in 2002, Shadid said, he kept hearing “crazy stories about what was going on” at the Iraqi prison, but he couldn’t believe U.S. troops would do what was rumored. He learned a hard lesson, he said: “Don’t believe everything. Don’t disbelieve anything.”

Published in the Summer 2011 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.