An Unexpected Landing

A former Badger rower traded boats on Lake Mendota for fires in the Wild West.

PHOTO GALLERY

See more of the Great Basin Smokejumpers.

“Roll call. Ro-o-o-o-ll call.”

The loudspeaker crackles and reverberates through the loft. A steady stream of denim and flannel flows into the ready room as twenty-some men take seats on wooden benches. Roll call begins.

Atkins? Yo. Hayes? Here. Zuares? Here. “Jinks?”

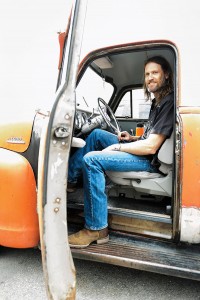

“Yah!” shouts a tall man with pigtail braids. He’s surveying the crowd from the back of the room, arms folded across his chest. You can barely see that, beneath the bill of his faded green baseball hat, his eyes are a deeper blue than the expansive sky that’s opening up over Boise today.

Roll call gives way to today’s business. Mainly, it’s lost items. There aren’t any extra radio antennas, so if you didn’t keep track of yours after last season, search through people’s gear. The keys to the brown 4×4 pickup truck and the key to the operations room are missing. Also, a distressed husband misplaced his wedding ring in the weight room. “He said, ‘If it’s put back where it was, I won’t ask any questions,’ ” says the man at the front. Someone whistles a descending scale. Jinks starts to smile.

“Zuares, go get that ring from the pawn shop!” a voice from the front shouts.

“Hey, that’s a hate crime,” snips someone in the middle row. Laughter rises until a nasal voice fires back, “Whatever, Trump!”

The room erupts. Jinks tries to refocus: “I was looking for the keys to my old truck last night at home, and I can’t find ’em …” he starts, and the room quiets. Beanies and baseball hats snap around to the back of the room. “So if any of you guys were in my house …” his words bubble into a laugh. The men follow suit.

The tall man with the pigtails is Todd “Jinks” Jinkins ’96, deputy chief of the Great Basin Smokejumpers. It’s refresher training week for the veterans, and today is the first active jump after winter break. Smokejumpers are the navy SEALs of firefighting. They rely on elite skills to launch the initial attack on a wildland fire. Fighting fires in the wild is highly specialized work, but smokejumping is more specialized still. They don’t battle raging, 50-meter-tall blazes; instead, the crew of eight, far from help, works on small fires before they grow into monsters like the one that consumed 3,000 acres of Northern California in August. During the spring-to-fall fire season, the smokejumper base tracks lightning storms and clusters of less-threatening fires to determine areas that could be in danger. A crew is then dispatched to those sites — in the most remote areas of the western wilderness.

The rookies train outside of Boise in an area they call “the units,” developing skills such as rappelling and climbing before progressing to training jumps.

That’s the smoke. Then there’s the jumper. “Some people take the bus [to work],” Jinkins says. “We just happen to take a parachute.” The only way to get to the work sites is by jumping from a Twin Otter airplane.

Though the career has been around for nearly eight decades, it’s unfamiliar to many. There are only nine smokejumper bases in the nation and fewer than 400 smokejumpers total. The Boise and Fairbanks, Alaska, bases operate within the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) system. The other seven are run by the U.S. Forest Service.

The morning meeting comes to a close. It’s been months since the guys have actively jumped, so today’s goal is to knock the rust off. “Slow and safe is the theme,” the final presenter says. “And, like always, have a landing you can walk away from.” The men nod silently. “Ground crew’s launch time is oh-eight-thirty. Tentative suit-up for oh-nine-ten.”

Wooden benches scrape against cement, NPR quiets the chatter, and another day with the Great Basin Smokejumpers is under way.

A NEW KIND OF CREW

There’s a trend of former UW rowers becoming smokejumpers. Jinkins was inspired to head out west by former rower Kurt Borcherding ’90, who had returned to campus to help coach the crew. Borcherding credits rower Lynn Tikalsky ’91 with opening the connection and helping him get started. And crew alums Eric Kafka ’93 and Matt Imes ’94 headed out to Boise with Jinkins in the nineties. “[Smokejumping] takes a mental toughness,” Borcherding says, “and I think a lot of the rowers have that.”

GEAR

The still, brisk air is shattered by the first flights taking off from Boise Airport. Across the commercial tarmac, the red, white, and blue Twin Otter waits for the first load of jumpers. The smokejumper building is located within the larger National Interagency Fire Center campus. Just beyond the security gate, the parking lot is saturated with pickup trucks and rusty Subarus. The walkway is lined with deer antlers. A suited-up mannequin stands in the entryway of the loft, outside of the small office that Jinkins shares with base manager Jim Raudenbush.

Jinkins meanders through the narrow hallway that’s been turned into a mini-museum on the history and practice of the profession. He points to the suit, explaining that just about everything a smokejumper needs is attached to it: a RAM-AIR parachute, a reserve chute, and a drogue chute to slow his descent; a 150-foot rappel rope in the right leg pocket; and a gear bag attached to the front that holds a hard hat, drinking water, some food, and a fire shelter. Once the smokejumpers hit the ground and receive their cargo, the gear bags transform into backpacks.

The real work doesn’t begin until the jumpers have parachuted to the landing spot from 3,000 feet, set up base camp, and hiked to the work site. An average shift lasts 16 to 18 hours. “We’ll get up at six, work all day, and usually try to be back to camp by 10,” Jinkins explains. “Get some sleep and do it all over again.” When the job is done, be it two days or two weeks, they haul everything to a helicopter landing spot or hike to the closest road — sometimes 20 miles away. Packed up, all of the gear weighs around 110 pounds. “It’s not light, so it’s not fun,” he says, “but it’s part of the job.”

Once the crew receives a fire call, it has six minutes to suit up and taxi out in preparation for takeoff to the site of the blaze.

SUIT-UP

Todd Jinkins is not a slacker. But, one period during his senior year at Iowa–Grant High School in southern Wisconsin, he skipped class to see a Marine Corps recruiter in the guidance counselor’s office. Maybe it was to learn about the marines, or perhaps it was because the recruiter was a buddy of his. “I went home that night and told my parents I was going to join the Marine Corps. They said, ‘No, you’re not!’ ” Jinkins, like his four siblings before him, was supposed to attend UW–Madison. But at that point, he wasn’t one for supposed-tos. Instead, he waited until he turned 18 and left for boot camp.

That’s how he landed in the middle of the first Gulf War. He remembers hitting the beach in the amphibious assault of Kuwait. He remembers taking 5,000 POWs who had endured 45 days of bombings. He remembers watching the U.S. Air Force liberate Kuwait City while the marines held down the outskirts. But he’s quick to say that his experience doesn’t compare to that of current military men and women. “There wasn’t nearly as much fighting; there wasn’t nearly as much death,” he says. “I’m glad I had the experience, but I couldn’t do it over again.”

After four years in the marines, Jinkins put in four years at the UW. Adjusting to college life was hard, especially as a 22-year-old freshman, but not impossible. “I was so much older and had done so many more things than all of these other people,” he says. And after serving in the military, he was used to regimen. Luckily, he found a way to get it on campus. Dan Gehn ’89, then a freshman rowing coach, spotted six-foot-three Jinkins in line enrolling for fall classes. Jinkins had never rowed before, nor had he any ambition to do so. He even forgot about the tryouts until Gehn called to remind him.

It was while rowing for the UW, at a time when the rowing team wore varsity hockey hand-me-downs with Crew scribbled in Magic Marker, that Jinkins learned about wildland firefighting. Kurt Borcherding ’90 had come back to help coach the freshman team after working in the Sawtooth National Forest on a hotshot crew — a type of wildland firefighting that involves busing to work sites rather than parachuting. “My job kind of piqued Todd’s interest,” Borcherding says.

After they both achieved smokejumper status, the two worked together in Boise until Borcherding went to the Alaska Smokejumpers in 2008. “It takes a special breed to make it through the BLM system,” Borcherding says. “You have to be a little bit crazy to want to hang out in the woods with a wildfire burning right next to you. You’re working 18 hours a day, and you’re basically a glorified ditch-digger. If you can put up with that, there are so many perks to the job.”

Smokejumper Dictionary

Loft:the smokejumper building on the National Interagency Fire Center campus; in the winter, the smokejumpers turn the loft into a sewing factory to handmake all of their gear bags, suits, and harnesses.

Hotshot crew: a handcrew of 20 firefighters trained in suppression tactics; they drive as close to the sites as they can to begin work.

Stick: a group of jumpers who are in the air at the same time; a two-person stick means that two jumpers are kicked out of the plane.

Burbs: a group of Chevrolet Suburbans.

Six-packs: Ford crew cab 4×4 pickup trucks.

LAUNCH

“Seth, tuck me in!” One of the ground-crew guys has decided to nap in a corner of the orange canopy that marks the jumpers’ landing spot. Seth gingerly places a grapefruit-sized rock on top of him. “There you go, buddy.” Someone asks if anyone is going to wake him, but he insists nobody will land that close.

“Dude, Adell’s gonna nail it. He’s gonna be right here,” one points to the rock.

“I got Mel as my dark horse,” another quips.

“Mel’s gonna be too far downwind!” shouts the canopy. Somebody has already bet on “Skinny Jinks” to hit the target. The young guy taking bets asks David Zuares, the field-operations supervisor, if he wants in. Zuares walks away, his hands shivering as he wipes his nose with a handkerchief. “This load that’s coming, that’s all the old salts. They’re very good at what they do,” he says. So is he, with more than 200 fire jumps under his belt. “They’ll all be stacked up right here,” he nods toward the canopy.

At promptly oh-eight-thirty, Zuares leads the caravan of three burbs and two six-packs to a field in Mountain Home, Idaho, a small air force town 50 miles south of Boise. The rigs park off of a two-lane road. Cattle graze freely on the other side as a tumbleweed skids past a hollow animal skull. The guys try to recall if anyone has landed on that side of the road, at a spot some 50 yards away. If anyone has, they can’t remember.

“This is the easy jump spot,” Zuares starts at normal volume but ends in a shout, “because it’s frequently windy here!” He makes no claims to be an aeronautical engineer or physicist, but he explains, in depth, the difference between airspeed and groundspeed. A windier day on the ground makes for a softer landing.

The radio lying next to a prairie dog hole crackles: Jump spot, jump four–nine.

Jump four–nine, this is jump spot, go ahead.

Because a reserve parachute is a last resort, packing one requires a Federal Aviation Administration license. “It’s almost like a pilot’s license, but for parachuting,” Jinkins says.

The plane is on its way. The ground crew responds to report consistent winds out of the west at eight to ten miles per hour. The mission is simple: land on the canopy (no longer occupied). The execution requires teamwork among the eight jumpers, one spotter, and the pilot aboard the Twin Otter. A hum breaks through the sky as the plane comes into view. Pilot Diego Calderoni orbits the canopy several times on a low pass. If this were an actual fire jump, the spotter would be looking for fences, large rocks, and other ground hazards. On the third pass, the plane climbs to 1,500 feet. The spotter, dangling out where the door should be, kicks out two streamers. The 15-foot strands of red and yellow are weighted to show the jumpers exactly which way and how fast the winds are blowing. “I would suspect they’ll land about 400 yards [northwest] of the canopy,” Zuares guesses. He’s right.

A second set of streamers falls out into the wind line, aiming for the canopy. This gives the spotter an indication for where the exit point will be, Zuares explains. The plane ascends to 3,000 feet, and the spotter has a few moments to mentally calculate the new exit point at the new altitude. Once he’s done that, the first jumpers exit the plane.

Jinkins says that Mickies Dairy Bar on Monroe Street was the favorite hangout spot for the crew after practice. “I take my wife to Mickies when we go back [to Madison],” he says. “It’s good to see that some of those places don’t change.”

CHANGE COURSE

“Who’s the mayor of Madison?” Jinkins wants to know. He’s the kind of guy who wants to know a lot of things. He wants to know what people across the world thought about the 2016 presidential race. “It is a little bit of a sad commentary on Americans. This is such a spectacle, in a bad way,” he muses. He thinks that recruiting female smokejumpers is akin to increasing women’s enrollment in STEM majors, and will require more resources and backing. He wonders how Netflix’s Making a Murderer relates to his own jury experience. Jinkins laughs that his political and behavioral science degrees haven’t done much for his career, but he doesn’t think that’s what UW–Madison is about. “It teaches you how to think. It teaches you to apply reason to why you’re doing something,” he says. “Use some cognitive thought and scientific background to make a decision. That’s what you get out of a liberal arts degree.”

In another life, Jinkins might have been an engineer. He builds things. In the off-season, he sets up a drafting table at his favorite downtown café, the Flying M. There, he designed and built the three houses that he and his wife, Tobey, have lived in. He also puts cars and motorcycles together, the latter of which he takes on a long ride each fall. He and some smokejumper buddies ride the back roads from Boise to Canada and back in memory of a fallen smokejumper and close friend.

To Jinkins, knowledge is best when shared. The U.S. Forest Service has sent him to Oman and Mexico to teach courses about incident command. He hopes to get to Mongolia and Africa next. Tobey has suggested that, when he walks away from smokejumping, they could join the Peace Corps together. But for now, he’ll commute by parachute. “Smokejumping has been a pretty amazing career. It’s fun to think that I can be having breakfast in southern Nevada and dinner in Fairbanks,” he says. “The earth is a pretty amazing place. That’s what keeps people coming back for the job.”

Jinkins grew up in Montfort, Wisconsin, population 709. His high school combined five neighboring towns, including Cobb — hometown of Badger men’s basketball head coach Greg Gard. “His mom was our high school secretary,” says Jinkins.

LANDING

The winds on the ground have picked up. The crew radios the pilot, who’s already climbing to 3,000 feet. No response.

The first refresher day went according to plan. As Zuares suspected, the first load of jumpers was stacked up around the canopy. Raudenbush landed right on target. Jinkins insisted that he would have, if “Bush” hadn’t been in the way. Today, things are not going according to plan.

The guys had hoped to jump some rougher terrain outside of Emmett, Idaho, 45 minutes north of Boise, but the week’s rainfall put them back in Mountain Home. During initial radio contact, winds were at five miles per hour. The ground crew is now bracing against relentless gusts.

Jump four–nine, this is jump spot calling blind. Winds on the ground increased to 15–17.

“Hope they get that,” the caller says to no one in particular. Yesterday’s winds were perfect, but there’s a quick cutoff between ideal and too high. The BLM smokejumpers cover the intermountain desert area of the Great Basin and Alaska, where high winds are common. That’s why they use the RAM-AIR parachute; it can sustain higher winds than the standard round chutes used by Forest Service jumpers.

“It can be a trick not to get dragged and injured,” Jinkins says. When it’s windy, the canopies stay inflated and make it harder to cut away. He remembers a jumper who used a round chute for a beach landing on the windy Bering Sea. He broke both of his arms on impact, making it impossible to pull the cut-aways to deflate the chute. “Luckily there was some driftwood on the beach, and his canopy got caught up on [it] and stopped him before it dragged him into the ocean,” Jinkins chuckles. He and the guys are used to harrowing experiences. “I wouldn’t say it’s super dangerous,” he shrugs. Last summer, a 60-foot-tall tree fell over and landed square on Jinkins’s back. He was sent on his sixth life-flight medevac with just a few broken ribs.

Smokejumpers have engineered their suits to protect against injuries. The material is a Kevlar/Nomex blend: resistant to fire and puncture. “We have had situations in the past where people have kind of been … skewered,” Jinkins says. Phil Lind, a Prairie du Chien native, is one such kebab. In 2005, a windless landing brought him in too fast, and he skidded into a tree branch. “It went almost all the way through him.” Jinkins explains with gestures, “He pushed himself off, but a lot of his intestines started coming out.” He smiles. “Poor Phil.”

The plane still hasn’t responded to the blind call. It’s clear as soon as the first stick (or group of jumpers) hits the sky that they didn’t get the message. The closest guy lands about 50 yards from the target. “What the hell are they doin’?” someone laughs. “Jinks!”

Jinkins’s blue and yellow chute passes the target and continues in the wind line. He clears the rigs parked at the edge of the road and keeps going. Eventually, he lands closer to the grazing cattle than the rest of his company. He’s too far away to hear the heckling as he starts to de-suit, pack up, and trek over to the rigs. Today’s post-jump evaluator, a young guy in a camo hat, meets Jinkins by the 4x4s. They both shrug and start laughing. “Skinny Jinks” wastes no time giving the other guys crap for missing the target, too. He might not have landed where he expected to, but like always, it was a landing he could walk away from.

Chelsea Schlecht ’13 is a writer for On Wisconsin and is no longer certain she wants to try skydiving.

Published in the Winter 2016 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.