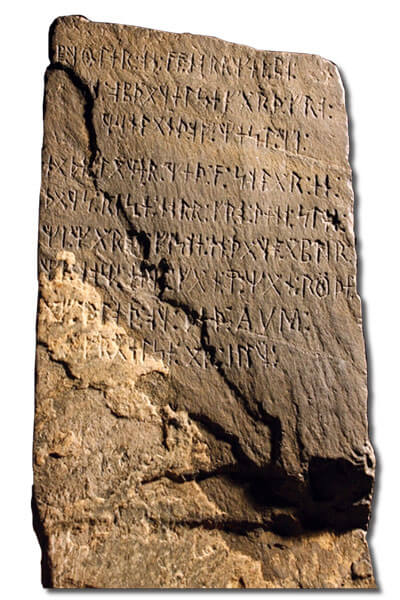

A Rune With a View

The Kensington Runestone, unearthed in Minnesota more than a hundred years ago, continues to spark curiosity and controversy. Is it evidence of Viking exploration of the Midwest? Or is it just a hoax?

James Frankki scours stones for evidence that proves America’s Viking past — or maybe not.

Ultimately, it was the mysterious symbols that gave it all away.

Of course, all the symbols were mysterious, as was the stone they were carved on. James Frankki ’85, PhD’07 was looking at a purported runestone, after all, one found in a forest outside Kansas City, Missouri.

A runestone is a rock carved with runes — letters used by ancient Germanic and Scandinavian peoples. The bulk of the markings on this particular stone were in a script known as the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc, an alphabet used by the early English between the fifth and eleventh centuries. But then there were other symbols — a vertical line and three pairs of diamonds, also arranged vertically. These were not runes. So what were they?

“If the writing isn’t all in the same [alphabet], it raises questions,” Frankki says. “Why would someone write in two different alphabets?”

The question of the symbols ultimately unspooled all the other questions that the Kansas City runestone raised, not least of which was how it came to be there.

When the stone was rediscovered in January 2011, its finders wondered if it was proof that early English mariners had somehow traveled all the way to Missouri more than a millennium ago. Was Columbus, sailing the ocean blue, a late-comer in fourteen hundred and ninety-two? Were Leif Ericson and his Viking companions covering someone else’s tracks when they touched on the coast of North America? Was this stone going to rewrite America’s history books?

These are just the sort of puzzles that Frankki enjoys. In November 2011, he joined a team of archaeologists, rune enthusiasts, engineers, and university students to look at the Kansas City runestone, read its meaning, and assess its authenticity.

A German professor at Sam Houston State University in Texas, Frankki hopes to see runology — the study of rune-based languages and artifacts — established in the United States.

“There aren’t any specialists in runology in this country,” he says. “We have a few of these runestones, and nobody’s studying them properly. It’s a lot of amateurs that are doing this stuff.”

The Elder Futhark (shown here with transliteration) was used in Scandinavia from the second to the eighth centuries. The Younger Futhark and Anglo-Saxon Futhorc are similar. Each alphabet takes its name from the sounds indicated by the first six letters. Illustration: Barry Roal Carlsen

Frankki emphatically does not count himself among the amateurs, though he’s not a runologist or archaeologist. He has a doctorate in German and is trained in medieval literature, Scandinavian studies, and philology (that is, historical linguistics). But then, there are no American runologists, and so Frankki has become prominent in the efforts to examine North American runestones.

“I’m a member of the Association for the Advancement of Runic Studies,” he says. “My title is ‘trusted adviser.’ I do research for them, and they support me in some of my projects.”

With his large, bushy beard and two Ks in his last name (of Scandinavian origin, naturally), Frankki looks much like the popular image of the ancient Germans he studies. A Wisconsin native who grew up in Medford, Frankki spent his youth in the Scandinavian-American heartland, and in the vicinity of one of America’s most famous, and most controversial, runic artifacts: the Kensington Runestone, which was unearthed in Douglas County in central Minnesota.

Its fame grows in part from its location, amid the Midwest’s large population of Scandinavian immigrants, and its supporters believe it gives evidence that Vikings traveled there more than 800 years ago. The stone’s controversy is the result of its uniqueness — there are few supporting objects to suggest that Vikings traveled so deep into North America.

But it wasn’t the Kensington Runestone that inspired Frankki’s fascination with runes. He’d never heard of it — not until after he completed his PhD, moved away from Wisconsin, and was working as a visiting professor at Oklahoma State University.

When Frankki first enrolled at UW–Madison as an undergraduate, he was more interested in philosophy than philology.

“I was very interested in the nineteenth- and twentieth-century philosophers, people like Nietzsche and Kant and Schopenhauer and Hegel,” he says. “I wanted to read them in the original — that’s how I ended up learning German.”

After earning his bachelor’s, Frankki served a two-year hitch in the army and was stationed with the Third Infantry Division in Kitzingen, Germany, where he had the opportunity to put his language study to a more rigorous — if less academic — test.

“This was during the Cold War,” he says, “and there was no chance then of a war breaking out. It was kind of a European vacation, a chance to live in and experience European culture — though being in an infantry unit wasn’t all that much fun. But we had time off, and on a month’s leave, I rode the trains all over [western] Europe.”

After his enlistment was up, Frankki returned to Madison and eventually enrolled in the UW’s doctoral program in German, writing his dissertation on the thirteenth-century poet Ulrich von Liechtenstein. A move toward medieval literature required him to gain familiarity with a variety of dead languages, including Latin, Old French, Old High German, Old Saxon, and Old Norse.

“Once I decided to do medieval studies,” he says, “I had to learn all those languages.”

For Frankki, that desire to study his topic more deeply combined with an interest in words and puzzles — he’s a tournament Scrabble player, and ranked fortieth at 2010’s national championship.

In the years after he completed the coursework for his PhD, Frankki taught German at a variety of locations — at UWC-Waukesha, UWC-Marathon County, Oklahoma State in Stillwater, and then Sam Houston State University in Huntsville, Texas.

It was at OSU — or rather while taking a day off from OSU — that he first fell under the sway of runes.

On a weekend trip with his then-wife, Lisa, Frankki passed a billboard for Oklahoma’s Heavener State Park, advertising that the area offered a runestone. Lisa wanted to stop and visit, but Frankki initially resisted.

“Later,” he says, “I thought hey, I’m a German professor. I’m supposed to be interested in this kind of stuff. And so we went and looked at it, and it’s got these runes, this stone in the middle of Oklahoma. I couldn’t read the runes at that time — I didn’t know the alphabet then — but it was supposedly carved by Vikings in the eighth century, seven hundred years before Columbus.”

The mystery of the Heavener Runestone ate at Frankki, even after he left Stillwater and landed in Huntsville. There he learned that one of the most-published authors on American runestones, Richard Nielsen, lived nearby in Houston. The two struck up a friendship that developed into a collaboration on runic projects.

Like Frankki, Nielsen is not a professional runologist — he has a doctorate in engineering. But he’s studied with Swedish runologist Henrik Williams — “one of the premier runologists in Sweden,” according to Frankki.

Nielsen told Frankki about the Kensington Runestone and stoked his enthusiasm. Today, Frankki is the academic adviser to a Viking Club among the students at Sam Houston State. Together, they travel and look at America’s possible runic evidence, exploring the notion that Vikings left their mark on the Midwest.

“But how did [Vikings] get to Oklahoma?” he asks. “That’s the question I’ve been dealing with ever since.”

The runestone that first caught James Frankki’s attention was the one near Heavener, Oklahoma. Supposedly carved by Vikings, the stone has just eight characters. “But how did they get to Oklahoma?” he asks. “That’s the question I’ve been dealing with ever since.” Courtesy of James Frankki

Runes are letters developed for writing out early Germanic languages. The three best-known runic alphabets are the Elder Futhark, the Younger Futhark, and the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc — the term Futhark (or Futhorc) refers to the sounds indicated by the first six letters in each alphabet. Each script was used in a different region and at a different time.

The Elder Futhark, the oldest, was common in Germany and Scandinavia from the second to the eighth centuries. The Anglo-Saxon Futhorc was used in England and along the North Sea coast of Germany and the Netherlands from the fifth to the eleventh centuries. And the Younger Futhark was found chiefly in Scandinavia from the ninth century into the fifteenth century.

Rune use expanded during what’s called the Viking Age, from the late 700s until 1066, when Scandinavians pushed out from their homeland, trading and raiding, and colonizing Iceland and Greenland. But how could the scripts have reached the middle of North America?

“We know from records that about 30 percent of the ships that headed to Iceland never made it,” Frankki says. “So you can assume that they drowned in the Atlantic. But some of them could have been blown off course and hit the coast of North America. The Vikings had these terrific boats that they could portage almost anywhere. We know that they went up and down rivers all over Europe.”

With the technology that Vikings possessed, Frankki believes that they might have been capable of making the journey to the American interior. Perhaps they pushed up the St. Lawrence River into the Great Lakes. Or perhaps they traveled overland from the coast. Or perhaps they sailed south around Florida, and up the Mississippi.

“They could have gotten there. I tend to think it’s most likely that they came through the Gulf of Mexico,” he says. “Even though,” he adds, “it’s [all] probably unlikely.”

The Heavener Runestone that first inspired Frankki contains just eight symbols, all in the Elder Futhark, and it reads either GNOMEDAL or GLOMEDAL.

“It’s a bit unclear as to whether the second rune [stands for] an N or an L,” Frankki says. “The problem is that sometimes runes could be written retrograde — in reverse, mirror image. But basically it seems to be a name: GNOME or GLOME of the valley — DAL means valley.”

The Heavener stone is hardly the most extensive runestone claimed in North America, nor the most famous. That honor belongs to the Kensington Runestone, which has 222 characters and tells a brief story: some thirty Scandinavians were on a journey when they stopped to do some fishing; upon returning to their camp, they discovered ten bloodied corpses. “Ave Maria, save us from evil,” the stone ends, giving the date 1362. A Swedish immigrant named Olaf Ohman discovered the stone in 1898 — it had been lodged in the roots of a tree he was digging up.

Or maybe not — the Kensington Runestone, as well as the one at Heavener and others in North America, is not widely accepted as genuine.

The trouble is this: although we know that medieval Vikings came to North America nearly five hundred years before Columbus, the solid evidence of their travels is limited to just a couple of sources: the Vinland Sagas and an archaeological site in Newfoundland.

The Vinland Sagas are epic poems that tell of Erik the Red, an exiled Norwegian who founded a colony in Greenland, and his son, Leif Ericson, who captained an expedition west to North America (which he called Vinland, after the grape vines he found there). But the sagas were written down about two hundred years after the events they describe.

More convincing to modern archaeologists are the ruins of a Viking settlement at L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland. Discovered by Norwegian explorer Helge Ingstad and his wife, archaeologist Anne Stine Ingstad, in 1960, the artifacts and remains they found were consistent with Norse settlements in Iceland and Greenland circa A.D. 1000. To date, this is the only confirmed physical evidence of the medieval Scandinavians west of Greenland.

The North American runestones — at Kensington in Minnesota, Heavener in Oklahoma, Spirit Pond in Maine, as well as others — may provide further physical evidence, or they may be frauds and hoaxes, created to capitalize on enthusiasm for a mysterious, medieval past.

The Upper Midwest is chock full of the descendants of rune-users. Some 13.5 percent of the people in Wisconsin — more than 700,000 — claim Scandinavian descent. Another 1.5 million Scandinavian-Americans live across the border in Minnesota. In addition, more than 42 percent of Wisconsinites and nearly 38 percent of Minnesotans claim German ancestry. It’s little surprise, then, that the Upper Midwest has sustained a fascination with the Kensington Runestone, in spite of its early rejection by the academic community.

“When the so-called experts looked at the stone initially, they just brushed it off,” Frankki says. “They didn’t study it properly. But they were in a position of authority, and people just believed them, and they just wrote it off as a hoax.”

Frankki hopes to give these North American runestones a more proper test for authenticity, but the task is far from simple. Many of the stones that are currently known have been removed from their original location or damaged in some way, so conducting an archaeological dig is difficult. Instead, Frankki says, those who study the stones must rely on linguistic and historical analysis.

“The first really important rune studies came out in the 1860s,” Frankki says, including in particular the four-volume Old-Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England by George Stephens, published beginning in 1866. Any stone discovered since then, Frankki admits, faces “a possibility that someone could have copied it” from Stephens’s or later texts.

None of the North American stones can claim a provenance that runs longer than the late nineteenth century. “There’s oral tradition on the Heavener stone that goes back to the 1830s,” Frankki says, “but oral tradition is not enough to establish authenticity.”

But even without the required provenance, linguists can examine the runes used to see if they belong to a known alphabet and if they use language appropriate to the time when the alphabet was in use. After that, one may examine the stone’s history and authorship. “The next step is to [try to find out] who carved [the stone] and when did they carve it,” Frankki says.

In 2011, he traveled to the site of the Heavener Rune Stone in Oklahoma and met Henrik Williams, who had come to examine the inscription, in order to determine whether the runes carved on the stone might be genuine.

“At Kensington,” Frankki says, “the debate is whether it was carved in the nineteenth century or the fourteenth century. When Dr. Williams was up there, he was looking to see if certain runes that have dots in them actually existed on the Kensington Runestone. The existence of dots on certain runes in the inscription had been claimed by other researchers, who wished to use this evidence to claim that the inscription was medieval. But it turns out he didn’t find the dots.”

The Kensington Runestone’s authenticity may still be a topic of debate, but the stone in Kansas City isn’t. It was the mysterious symbols, the line and diamonds, that put a date on the carvings there. The non-runic marks provided clear, definitive proof that the stone was carved not in the middle ages but in the nineteenth century.

When, last November, Frankki and others traveled to the Kansas City area to see the runestone, they went with open minds. The team measured and photographed the artifact and sketched the site. Frankki took pictures and made a sketch of the stone itself, copying out the thirty-seven runes and symbols to examine in greater detail.

And eventually the nature of the symbols became clear — they were numbers: 1888, the year in which, Frankki believes, the stone was carved. The inscription appears to be the names of English immigrants who arrived in America that year.

And so the stone may be a genuine runic monument, but it’s a thousand years younger than its discoverers hoped. Still, Frankki believes it’s important to study North American runestones with scientific objectivity, as one may yet turn out to be authentic.

“The idea is, it’s possible,” he says. Medieval Scandinavians “had the technology. They sailed all over Europe. They even circled the entire Mediterranean, and then they explored the Atlantic all the way across. So we don’t have the proof, but we have the possibility.”

John Allen is senior editor of On Wisconsin Magazine.

The Viking Effect at the UW

“If you want to get people into a class, all you have to do is put the word Viking in the title,” says Susan Brantly, a professor in the UW’s Scandinavian Studies department. “They’ll come.”

UW–Madison has been aware of the grip that Vikings and their descendants hold over the Midwestern imagination for more than a century. The UW’s Scandinavian Studies department is the oldest in North America, established in 1875 by Rasmus Anderson and developed into prominence by legendary professors such as Julius Olson 1884 and Einar Haugen.

“Due to the demographics of Wisconsin, there’s always been a strong interest in Scandinavia here,” Brantly says. “It’s part of the state’s heritage.”

Today, Kirsten Wolf, a medievalist who teaches Old Norse language and literature and Scandinavian linguistics, chairs the department. Though it has only five faculty, Scandinavian Studies serves forty undergraduate majors and offers three graduate degree tracks — literature, philology, and area studies. In all, nearly 1,300 students took one or more courses from the department in the last academic year. That includes courses featuring perennial favorites such as Hans Christian Andersen or even the latest Nordic sensation, Stieg Larsson. Among the most popular topics, Wolf says, are those that touch on the Viking age.

“People like Old Norse language and literature,” she says. “That literature is very rich and entertaining.”

J.A.

Published in the Spring 2012 issue

Comments

Steve Budapest July 7, 2012

Many letters of the Kensington Runestone are identical to the Old Hungarian Script (still in use, mostly in Transylvania, but coming back into everyday use here in Hungary too).

Apparently Hungarian culture is the oldest of human civilizations, and it goes back to 5000 BC, see Tartaria tablets (7200 years old) scripture found at a village near River Maros (Mures) in Transylvania (Hungarian territory, but now under Romanian occupation since WW1).

Interestingly, a Hungarian scientist Juan Moricz found similar scriptures in an Ecuatorian cave system, called Los Tayos Caves, in the 1960s.