A Refuge for Hope

During the refugee crisis in Greece, Amed Khan ’91 found a way to bring humanity to an inhumane situation

Amed Khan’s first trip to the Greek island of Lesbos wasn’t planned.

He was traveling by train to Milan, Italy, from the French Riviera in July 2015 after attending a fundraiser for actor Leonardo DiCaprio’s charitable foundation. Along the way, he noticed refugees camped out at railway stations. Khan ’91 decided to get off the train and follow their route backward.

When he got to Lesbos, thousands of people were landing on the country’s shores, wearing fake life jackets and crowded in rubber boats like cattle in a stockyard. Many arrived without their families or belongings, and others didn’t even make it that far. A number of boats sank midway through the journey across the Aegean Sea, and hundreds lost their lives in their quest to flee war and terrorism in their homelands.

“It was the startling contrast between the hedonism and extravagance of the people in Saint-Tropez and the awful conditions of these war refugees — who had lost all through no fault of their own — that compelled me to do whatever I could do to advocate for them and try to help,” Khan says.

Greece was the first step to freedom for refugees — mainly from Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan — seeking safety in Europe. But the country, facing both political instability and the worst economic crisis in its modern history, was not prepared to handle the mass migration of refugees that represents the largest population movement since World War II.

“The scenes were as horrible as anything I have ever seen in any situation,” says Khan, who served as chief administrator and logistician for refugee camps in Tanzania following the Rwandan genocide in the 1990s.

But this was Europe, “theoretically, the leader of civilization on earth, a place of marvels, an unbelievable structure of efficiency,” he says. “How is it possible that people were coming on rubber boats, drowning, sleeping on the streets, and then being shuttled off somewhere?”

Khan’s trip sparked an idea — to build a refuge for people who had lost everything, a place where they could hold on to their dignity and privacy, and find some hope for the future.

• • •

While Lesbos became known as the entrance to Europe for the wave of refugees, Idomeni, a village on the Greek border with Macedonia, became the exit. Despite having a population of merely 150 people, Idomeni ultimately became Europe’s largest unofficial refugee camp, with 15,000 people at its peak.

The Idomeni camp was evacuated in May 2016, and things got even worse for refugees. The European Union and Turkey reached a deal to control the flow of migration, essentially trapping 60,000 people in Greece who are seeking asylum. With borders closed, authorities rushed to set up refugee camps in northern Greece, where conditions can only be described as inhumane.

“In the beginning there were no toilets, no showers. It wasn’t safe,” says one Syrian woman who came to Greece with her child and lived in Idomeni before moving to a government-run refugee camp. “It was a tragedy. If you are in exile, they move you in these camps. It feels like we are taken to these camps to be punished.”

Khan saw the horrid conditions in Idomeni and, on subsequent visits, the other camps in northern Greece. “These people had lost their homes, their place of business, their schools, their communities,” he says. “Basically, they were running for their lives, and now they were in limbo.”

He reached an agreement with Greek officials to take possession of an abandoned textile factory in Thessaloniki, which the government had intended to turn into a refugee center. Khan worked with his close friend, Canadian philanthropist Frank Giustra, to redesign the more than 60,000-square-foot building. The two men put together the $1 million in private money needed for the project, and volunteers helped complete the renovation.

The center opened its doors in July 2016, two months after the Idomeni camp was shut down. The result looks nothing like a factory and, most importantly, does not remotely resemble most refugee camps. The center has room for up to 180 residents, who live in large, private rooms with new furniture and cabinets stocked with dishes. There are shared common spaces, including a large kitchen with multiple stoves, bathrooms, and community areas for women, men, and children.

It’s called Elpída Home. In Greek, elpida means “hope.”

A refugee boy rides a bicycle in front of Elpída Home.

Fatah (center), a refugee girl from Damascus, Syria, watches a chess game between refugee children in one of Elpída's community rooms.

Hakim and Omar play basketball at the playground of Elpída, built by volunteers and refugees.

Annie Rose, a volunteer doctor from the UK, organizes the pharmacy in the small hospital of Elpída, run by the Kitrinos Healthcare.

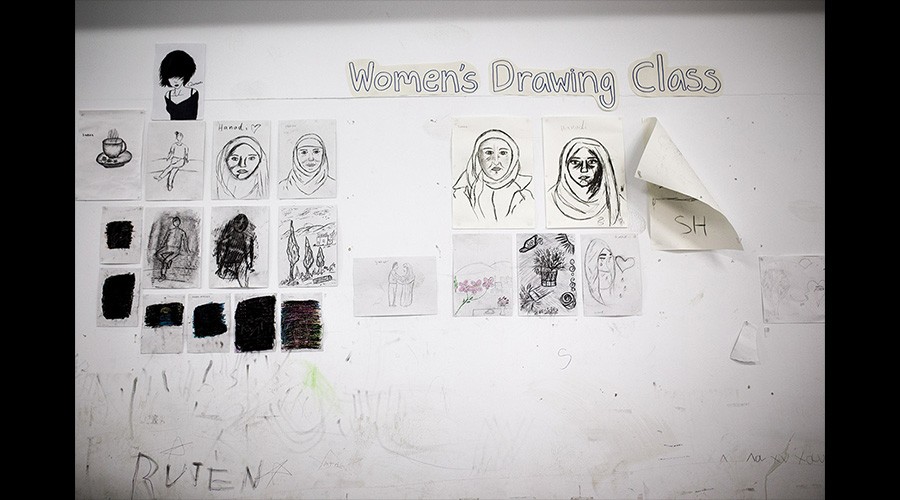

Drawings made by refugee women are exhibited in Elpída's main corridor.

Javie, a volunteer teacher from Spain, teaches English to refugee children at Elpída.

Hakim, a young Syrian refugee, watches a childrens’ television program on an Arab satellite channel.

A refugee woman prepares a meal for her family in Elpída's shared kitchen.

The Refugee Crisis

- Nearly 1 in 100 people worldwide are now displaced from their homes, the highest level since the aftermath of World War II.

- 34,000 people are forcibly displaced every day due to conflict or persecution.

- 54 percent of refugees worldwide come from three countries: Afghanistan, Somalia, and Syria.

- Children make up more than half of refugees; half of primary-age refugee children are not in school.

- During the past two years, 1.3 million people fleeing conflict and persecution have traveled through Greece in search of safety in Europe.

- Some 62,000 refugees are stranded in Greece.

- About 6 in 10 Syrians — an estimated 2.5 million people — are displaced from their homes.

- In October 2016, 54 percent of registered voters said the U.S. does not have a responsibility to accept refugees from Syria, while 41 percent said it does.

Sources: International Rescue Committee; Pew Research Center; United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)

• • •

Nasser, his wife, Sakina, and their daughter, Farah, arrived at Elpída when it first opened and moved into one of its large rooms after spending months sleeping in tents. Sakina is an artist and poet, and her paintings now hang from the walls. Colorful carpets and blankets give the room a taste of Syria. As Sakina brews a pot of flavored black tea, the family remembers its time in Idomeni and can’t feel anything but relief for ending up at Elpída.

For many residents, the most important part of living in Elpída is the feeling of safety and privacy they have while awaiting relocation. At the refugee camps, they had to worry about the few belongings they had being stolen. Here, they can lock their doors.

Volunteer teachers, including some refugees who live at Elpída, provide children with instruction, including lessons in math and English as a second language. Children also attend a local school to learn Greek. Food is provided, but residents are responsible for cooking their own meals. They also organize themselves, participating on committees to discuss ways to improve the center.

Team Rubicon, a disaster response volunteer organization staffed by U.S. military veterans and cofounded by Jake Wood ’05, set up and supplied a medical center inside Elpída in July. The medical team handed off care to another group in January after establishing a system to allow residents to access specialty services — including dental care, prenatal care, breastfeeding assistance, and psychiatric services — through other health organizations.

“We hope that we have injected some humanity into this situation, but one can’t help but think of the millions that are suffering,” says Khan, who is working with the Greek government to identify other buildings to convert to refugee centers. “The humanitarian assistance system is broken and it needs to be fixed; thus it is our collective responsibility to go all in to implement solutions.”

Khan’s early experiences at UW–Madison shaped his worldview and reinforced his desire to help others. He serves on the board of visitors for the UW’s political science department and remembers with gratitude the support professors gave him and the ideas they shared. One of his former roommates, Jason Obten ’92, spent five months in Greece to help Khan manage the Elpída project.

“When you are at Madison, you can’t help but feel that you are part of something. It gets into you and it stays with you,” Khan says. “Years later, I’ve been all over the world, worked all over the world, but I always feel that the Wisconsin experience played a large role in everything that I do to this day.”

After majoring in international relations and political science at the UW, he joined then–Arkansas governor Bill Clinton’s presidential campaign. After Clinton’s election, Khan worked in a variety of roles for the administration, including as director of operations for the G7 Summit of industrialized nations in 1997, and special assistant to the director of the Peace Corps, where he served as liaison to the White House.

“In everything that he has done since I’ve known him … Amed has been driven by a desire to help those who need help and to make a positive impact in the world,” Clinton says. “That desire is still there and is evident in the work he’s doing to help refugees in Greece. I’m very proud of him.”

Khan moved on from government to work with the International Rescue Committee in Tanzania, where he oversaw overall refugee camp administration and financial management. He also worked in Kenya for a conservation organization. Khan now lives in New York, where he directs Paradigm Global Group, a private international investment firm with a focus on commercial real estate, energy, and technology. He also serves as senior adviser to the Clinton Giustra Enterprise Partnership, a project of the Clinton Foundation.

Through it all, Khan has always had a special interest in refugees.

“Our politicians have carelessly sent billions of dollars of weapons to fuel and exacerbate the wars, but when it comes to dealing with the consequences, it’s easier for them to close the door and delude themselves into thinking they aren’t responsible for these destroyed human lives,” he says. “Leaving your home is always your last option. These groups of people are in the greatest need of protection.”

Marianna Karakoulaki and Dimitris Tosidis are freelance journalists who have covered the refugee crisis in Greece since 2015 and contribute regularly to Deutsche Welle, IRIN News, and other publications around the world. Follow their work on Twitter @Faloulah and @d_tosidis.

Published in the Summer 2017 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.