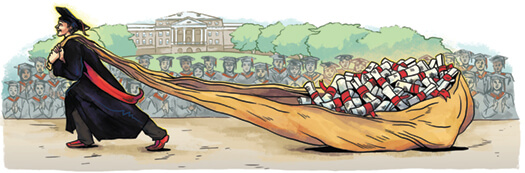

A Matter of Degree(s)

The UW just can’t get rid of some alumni — no matter how often they graduate.

Believe it or not, UW-Madison’s most-educated — or at least most-often-educated — student is not an alumnus.

George Green, a retired auto executive, completed some twenty distinct academic programs under UW guidance, yet he never earned a degree from the school, or even set foot in a classroom.

Green undertook his studies through the United States Armed Forces Institute, and he did so by correspondence. During World War II, Green was a GI serving in Europe, and while recovering from frostbite in England, he started signing up for classes through USAFI, which was then headquartered at the UW. It wasn’t entirely intellectual curiosity that drove him. Rather, his recuperation, combined with his pre-mobilization engagement to a girl in his hometown — Toledo, Ohio — limited his other options. “I didn’t really have any reason to go into town,” he says.

So instead he stayed at his base and studied. A lot. In just fifteen months in 1945–46, he scored a score of correspondence diplomas, setting something of a record. It’s right there in Ripley’s Believe It or Not. You can look it up.

But for all that, Green got his actual degrees elsewhere — at the University of Toledo and, later, at Michigan’s Wayne State. Which raises a question: who’s the UW’s most-educated student who’s also an actual alum?

Believe it or not, it’s a difficult question to answer.

Keeping Score

The trouble is, how does one really measure education? You could count all of the classes students take, but that doesn’t really say whether they learned anything. It seems to me that finishing a program of study ought to count for more than simply starting one, so I prefer to tally the number of degrees a student earns, not merely the credits accumulated.

But still, there are questions: Do double-majors count as two degrees? What about certificates, for those non-degree programs such as women’s studies or teacher training? Should graduate degrees be weighted more than a bachelor’s?

Add in education gained elsewhere, and the matter becomes even more complicated. The curricula vitae of some UW alumni are defaced with degrees from a variety of institutions, but frankly, I wouldn’t want to have to vouch for their quality: for instance, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (which is evidently some sort of trade school) or a “university” called Yale (named, I’m told, for Brooklyn mobster Frankie “Prince of Pals” Yale, an associate of Al Capone’s). No: if we open the door to such manifestly shady institutions as these, we might as well accept the validity of degrees granted by the Consolidated University of the Moons of Neptune.

So for this little experiment, I decided only UW-Madison degrees count. And for simplicity’s sake, double-majors are out, and we’ll count only completed degrees and weight them all equally.

By this standard, the UW’s most (often)-educated alum is one Robert Schubert ’74, ’75, MS’80, MA’83, MBA’92, JD’93, and that ain’t all. Believe it or not, he supplemented his six degrees with the UW Extension’s agricultural short course (1973) and an ABD (all but dissertation) doctoral program that earns him the additional alumni-magazine distinction of PhDx’88.

Tenacious Indecision

Schubert didn’t come to the UW bent on academic extravagance. His initial ambitions were much more modest.

“I always wanted to be a farmer,” he says.

But as a Milwaukee native with no farmers in his family, he needed a bit of training before launching an agricultural career. After two years at UW-Milwaukee, he transferred to UW-Madison and enrolled in the dairy science program. But the more he learned, the more he met distractions that would require yet more study.

When he was nearly finished with his bachelor’s degree, for instance, a romantic entanglement pushed him off course.

“My girlfriend at the time thought we should both become vocational ag instructors,” he says. “So even though I was in my senior year, I decided to get a second degree in agricultural education.”

That degree marked the beginnings of a sense of — call it tenacious indecision. He had the gumption to stick through almost any academic program to its conclusion, but found that careers were far less interesting to pursue than to plan. The ag ed program included a stint as a student teacher, which taught Schubert one important lesson: “I really don’t like teaching high school,” he says. “The instruction is okay, but I didn’t like the disciplinary aspects.”

So he reverted to dairy science, picking up a master’s but stopping short of a doctorate. “The biological sciences require a lot of lab work, and I’m not really a laboratory research kind of guy,” he says. “I kind of prefer the social sciences. So I switched to agricultural economics.”

This provided a second master’s and nearly a doctoral degree. (“You know how some people say their dissertation wrote itself?” he explains. “Well, mine didn’t.”) He admits that he might not have been able to afford all this study at today’s tuition prices. Even in the 1970s and 1980s, it was a struggle, and he supported himself with a range of work, on campus and off. He held standard student jobs, such as research assistant, but also nonstandard ones, including life model for the art department. He drove a bus for Greyhound and worked as a meat inspector for Peck Packing in Milwaukee. (“How I hated that job,” he says.) He also taught at UWC-Baraboo and through an extension program at the federal prison in Oxford. And he did buy a farm — a hundred acres in the Town of Vermont, Wisconsin, which he worked for several years and rented out for many more, and eventually sold for a half million dollars in 2004.

But ultimately, Schubert decided he needed to improve his marketability with another degree. He returned to the UW for an MBA, a plan that seemed wise until about halfway through. “Then,” he says, “I realized that if I wanted to make serious money, I ought to become a lawyer.”

While completing his business degree, he enrolled in law school, first at Marquette and then transferring to the UW, where he finished up in one year.

But he didn’t go into practice. Instead, he stayed on at the UW’s School of Business, becoming a member of the academic staff and serving as a proctor and grader for midterms and finals. He held that position for the last fifteen years, until his retirement in January 2008.

Now that he’s left the working world, Schubert doesn’t plan to finish his nearly complete doctorate, “though I admit it occurred to me,” he says. But he will continue to take courses, auditing them through the UW’s adult senior services program.

It is, he admits, a difficult transition. “What I really enjoy is the excitement of taking classes,” he says. “And trying to get the top grade is part of that. I’m still as much of a grade-grubber as any undergraduate.”

Heads of the Class

Believe it or not, Schubert doesn’t actually have a very large lead in the race for the title of the UW’s most-graduated graduate. Some twelve others have five distinct degrees, although two of the alums are dead and so unlikely to catch up.

It wasn’t always such a tight competition, though. Iva Mortimer ’20, MA’26, ’39, MS’40, PhD’47 was the first grad to cross the stage five times, and she held the record for nearly a quarter of a century.

Mortimer had good reason for seeking so much education, though it cost some thirty years of her life (making her, I guess, the UW’s most gradual graduate). She’d first come to the UW to study zoology, but had given up academia for love, marrying agronomy professor George Mortimer after she received her first master’s. After George died in 1934, she was left with a family to support, and as there were few zoological jobs for women in the 1930s, she turned to the more promising field of home economics. After completing three more degrees, she joined the faculty of what is today the UW School of Human Ecology, teaching food and nutrition until her retirement in 1965.

The Badger who finally came along to tie her record was Giancarlo Maiorino MA’68, MA’69, PhD’71, MA’71, PhD’73, and he did it in much less time. The key to his speedy collection of sheepskins, believe it or not, was simple.

“I pushed the system to the brink,” he explains.

Maiorino had taken his first steps toward higher education in his native Italy, though opportunities there were limited. His parents couldn’t afford to provide him with a classical education, and instead he received vocational training to become an accountant.

“The one thing I learned,” he says, “is that I could not be an accountant.”

He emigrated to America, ostensibly to study English at New York’s Long Island University, but while there he discovered a love of literature. He enrolled at UW-Madison because “it was the only western university anyone in New York had ever heard of,” he says, “and it was the first university to accept my application.”

Then things get a little dicey. In Madison, Maiorino knew that he wanted to study Italian, art history, and comparative literature, which would mean covering several different — if related — academic areas. Yet with limited finances, he also knew he didn’t have forever to spend in school, so he’d have to be clever as well as bright.

“I used my imagination and street smarts,” he says. Graduate students were allowed to take only three courses a semester, and needed special permission from their department chair and dean to take a fourth. “But registration wasn’t done with computers then,” he says, “and you were allowed to add or drop courses at will during the first week of each semester. So I just added more courses than I dropped. It worked.”

To ensure his workload didn’t overwhelm him, Maiorino again relied on street smarts. As most of his courses were related thematically, he coordinated topics for his papers, using them for multiple classes and combining them to form the heart of his theses and dissertations. By 1973, as he was finishing up his second doctorate, he realized he was accomplishing something unprecedented.

“I thought the university would be so proud of me,” he says. “Instead, I was treated like a criminal.”

When the grad school discovered Maiorino’s actions, a dean threatened to block his second doctorate. But as he’d amassed some 180 credits with the full support of his department, there was little anyone could do to stop him. He picked up his fifth degree and soon left to join the comparative lit department at Indiana University in Bloomington, where he became the Rudy Professor of comparative literature. He retired in 2008.

Within a couple of years of Maiorino’s departure, the number of mega-degreed graduates would shoot upward: Jaafar Al-Abdulla MS’57, ’64, MS’67, PhD’74, MS’75; Kathleen Lindas MS’64, MS’74, MS’75, PhD’77, MS’77; Lynette Korenic ’77, MA’78, MFA’79, MA’81, MA’84; Farhad Jafari ’77, MS’79, PhD’83, MA’86, PhD’89; Karen Michaelis ’72, ’74, MS’85, PhD’88, JD’89; and Teri-Christine Hall ’76, ’78, MS’82, MS’87, PhD’90 all tied Mortimer and Maiorino before Robert Schubert came along. And after Schubert, Joan Price ’84, MA’86, PhD’91, MA’92, MFA’93; William Schmitz ’85, MS’92, MS’93, PhD’97, MS’99; Terence Ow ’88, MS’90, MBA’92, MS’94, PhD’00; and Ryan Toonen ’99, ’02, MS’05, MA’07, PhD’07 also reached the five-degree plateau. But no one has broken Schubert’s mark, or even tied it.

Until, believe it or not, this August.

The Challenger

Like Robert Schubert, William Schmitz came to the UW from the Milwaukee area, and like Schubert, he also revels in the pleasures of course work, from intellectual discovery to the competition for grades.

“That desire to have the top score on every test, in every class, it’s in me,” he says. “After I got my PhD, I told myself I should just learn for the sake of learning. But [the competitive spirit is] still there.”

After receiving his bachelor’s in nursing, Schmitz left the UW for the working world. Though he says his siblings often ask him when he’s going to get a “real job,” he has one: he works weekends in the intensive care unit at Meriter Hospital, a position that pays a full-time salary, but leaves his weekdays free. He chose to use that free time on campus.

Schmitz became fascinated with the subject of workplace injuries, and began studying biomedical engineering. But he found that discipline “too boring,” he says, and eventually switched to the School of Education, hoping to teach people about safety. He earned his first master’s in curriculum and instruction, then a second in industrial engineering, and then followed that with a doctorate in the same field. A later master’s in nursing was, he says, largely for professional development.

Over the following decade, Schmitz kept active on campus, taking classes and working occasionally as a teaching assistant. He took part in the 2004 TA strike, helping to push for health care coverage for graduate assistants. That experience sparked an interest in the interactions between labor and management, and he followed up with graduate study in the UW’s industrial relations program — which will grant him a master’s degree this summer, tying him with Schubert at six.

But Schmitz may not stop there. He would have liked to get a second doctorate, also in industrial relations, “but the university canceled the program,” he says. Still, there are other degrees. In 2010, he plans to start work on a doctorate in nursing practice. And then what?

“Maybe I’ll go to law school,” he says.

Believe it. Or not.

On Wisconsin senior editor John Allen has two degrees, but none from the UW. Loser.

Published in the Spring 2009 issue

Comments

Rod van Ausdall October 4, 2010

I`ll always be glad I started my USAFI education, auspices of U WI in Bad Kreuznach, Germany and later in Mainz, Germany starting in 1954./Rod van Ausdall