A Freedom Rider’s Perilous Path

In between pickets and protests throughout the South, civil rights hero Dion Diamond x’64 did a stint at the UW.

Dion Diamond x’64 had an unusual after-school pastime. Starting when he was 15 years old in 1956, he conducted what he called “private sit-ins” at drugstore soda fountains in his segregated hometown of Petersburg, Virginia.

“I would get joy out of sitting at the whites-only lunch counter,” recalls Diamond, the son of a postal worker and president of his senior class. He typically waited until police came before running away. Other times, what he describes as his “very sponta- neous and haphazard” protests included browsing the stacks of the whites-only library. As always, he took off only when officers arrived.

He never told his parents what he was doing. “It wasn’t something I went home and bragged about,” he says.

He also never got arrested. That would soon change.

“I don’t know what motivated me in high school, except I just knew something was wrong,” says Diamond, who transferred to the University of Wisconsin from Howard University in 1963.

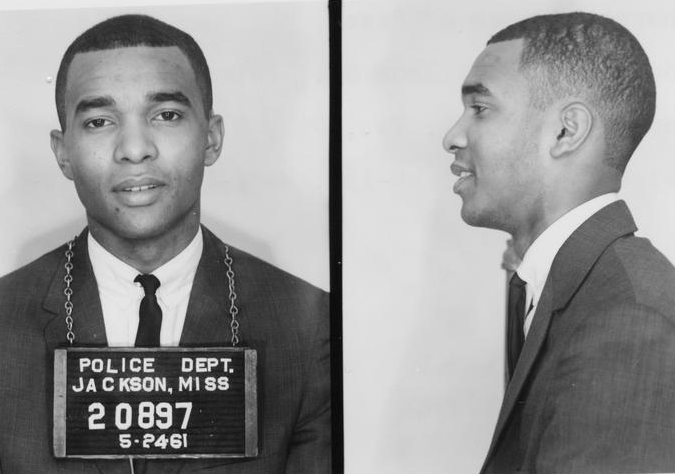

Now 83 and living in Washington, DC, Diamond became a Freedom Rider, one of those brave activists, mostly college students, who rode interstate buses in the South, facing angry mobs and imprisonment to challenge segregation. Then, as a voter-registration coordinator for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), he risked his life in Mississippi, Louisiana, and Maryland.

Police handcuffed him more than 30 times. (“Please check with the FBI for dates and locations!” he says with a chuckle.) The Supreme Court heard two cases resulting from his arrests. He served about a year in prison on different occasions, including two months in solitary. He endured slurs, death threats, and attempts on his life.

“Dangerously fearless and dedicated” and armed with “a quick wit” is how SNCC leader Stokely Carmichael once described his friend. Diamond calls his activism “youthful exuberance.”

“I hold Dion in awe,” says Freedom Rider Henry Thomas. “The number of times they tried to kill him, the number of times he was shot at — I don’t know all that he went through, but I know enough about it to say: how did you maintain your sanity?”

Today, Diamond, a retired human resources consultant, moves more slowly and sports a ready smile. Looking back on his activist days from the comfort of his desk chair in his home office, sunlight streaming in from wrap-around windows, he says, “I regret absolutely nothing that I have done. I have many regrets for what I have not done.”

“YOU WANT TO DIE?”

In 1960, North Carolina college students electrified the nation with sit-ins at a Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro. The news inspired students at Washington, DC’s Howard University, where Diamond, 19, was freshman class president and a physics major. “How can we be doing nothing?” he asked himself.

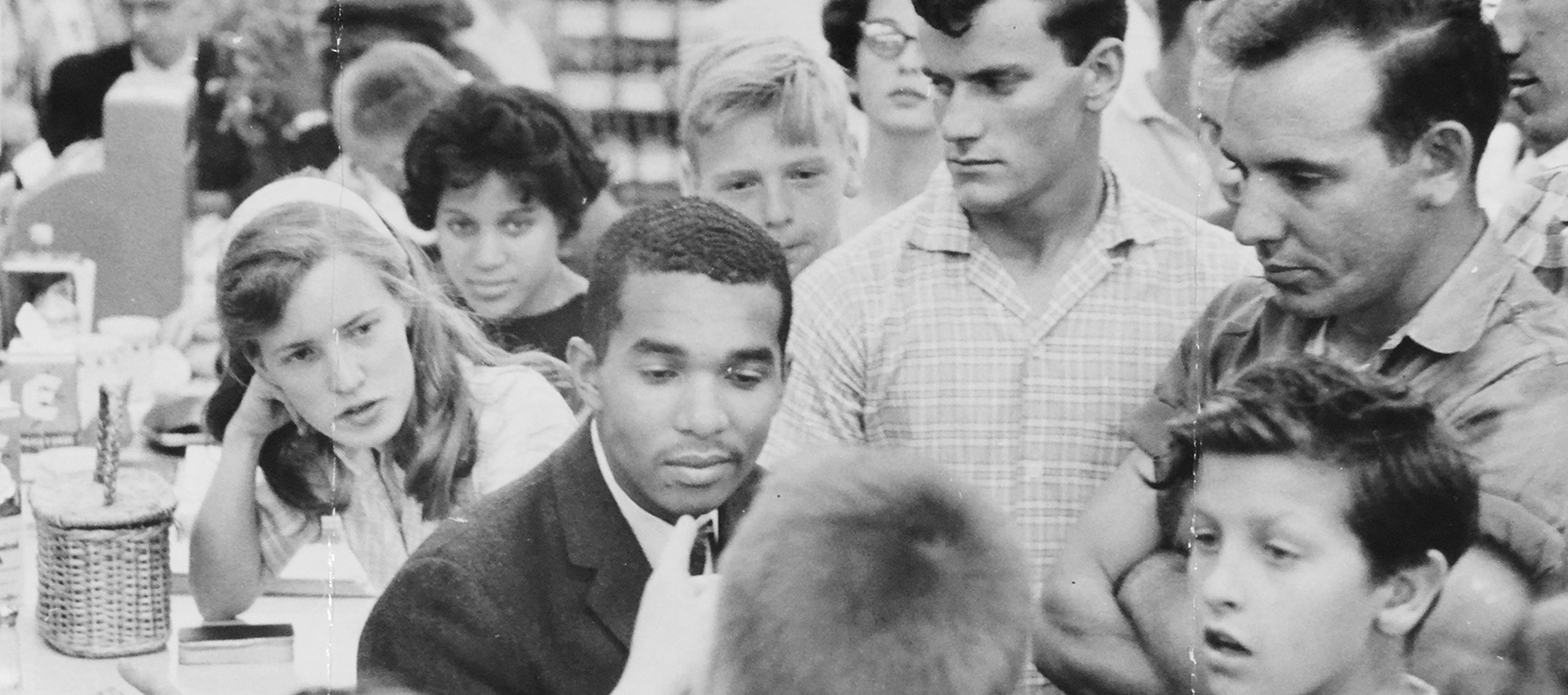

Soon, he and his classmates founded NAG, the Nonviolent Action Group. On the afternoon of June 9, a small group that included white members (to show broad support for the cause and get more publicity) held sit-ins at the Cherrydale Drug Fair and People’s Drug Store in nearby Arlington, Virginia.

At People’s, the manager closed the counter. When he refused to press charges, Dion and five others went to Drug Fair.

Police, having been tipped off, were waiting in riot gear. So were reporters and film crews. George Lincoln Rockwell, the head of the American Nazi Party, lived in Arlington. Soon he arrived with his followers — young toughs with ducktail haircuts and sideburns who wore brown shirts and swastika armbands.

Standing beside Diamond at the lunch counter, Rockwell asked, “Why do you go where people don’t want you?”

When Diamond made no reply, Rockwell added, “You want to die?”

Again, Diamond said nothing. He kept his hands on the counter.

“I regret absolutely nothing that I have done. I have many regrets for what I have not done.”

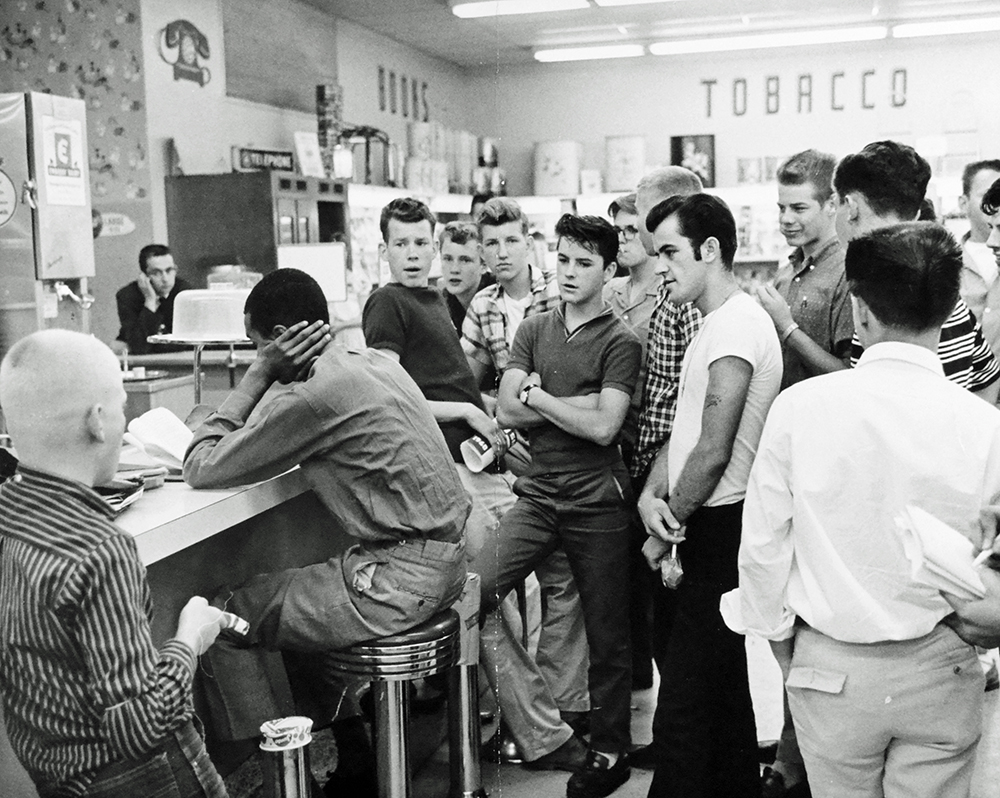

As a crowd of 300 gathered outside, Nazis put lit cigarettes on his seat and in a pocket of his pants. Thugs jabbed him with their elbows and tossed spitballs at him, according to Diamond’s account to a newspaper reporter.

“He was steadfast,” recalls Joan Trumpauer Mulholland, who sat beside him. “He got a cigarette or two put out on him, but he persevered and stayed nonviolent.”

The protesters eventually fled to waiting cars in “a hail of epithets, bricks, and lighted cigarettes that seemed literally to set the night air alive with fire,” according to divinity school student Laurence Henry, who took part in the sit-in.

The next day Diamond returned to Cherrydale — and at one point sat alone — to continue the protest.

“My training was strictly on the job,” he recalls.

Less than two weeks later, almost all chain drugstores and department stores in Arlington and Fairfax counties and Alexandria announced they would serve Black customers.

STOP! GLEN ECHO IS SEGREGATED

Flush with victory and perhaps thinking another local success might come swiftly, NAG began daily picketing of the segregated Glen Echo amusement park just outside of DC that summer, sometimes with several hundred Black and white protesters.

“Glen Echo is almost something like a flower, something that blossomed, something that bloomed,” Diamond said in a documentary about the protest, Ain’t No Back to a Merry-Go-Round.

Counterdemonstrators, some of whom were Nazis, started a competing picket line. Irrepressible, Diamond on at least one occasion walked next to them, a moment a newspaper photographer captured. Smiling, his chin jauntily up, and wearing a long-sleeved shirt and a tie in the summer heat, Diamond holds a placard that reads, “STOP! GLEN ECHO IS SEGREGATED.”

Police arrested protesters, some of whom were on the merry-go-round. Diamond was also taken into custody. It was not his first time in handcuffs. Earlier at a Howard Johnson’s restaurant, police charged him with trespassing. The Supreme Court overturned that conviction.

Walking with Diamond that summer was a UW student who told the Daily Cardinal in 1964 that “Dion is sort of an agent, a provocateur.”

He was a prankster, too. To drum up press coverage and highlight the absurdity of segregated facilities that admitted Africans but not African Americans, the picketers rented a black Cadillac limousine. Diamond, who had been in his high school drama club and won best-actor honors in his yearbook, donned a turban and dashiki. He sat in the back seat with a white female student who pretended to be his translator.

When the limo pulled up at the main gate, the elderly guard was “flabbergasted,” according to Diamond. He blocked Diamond’s path, but Dion commanded him in fractured high school French, “Je désire open the park maintenant.” (“I want you to open the park now.”)

“We didn’t get in,” says Diamond with a grin.

But once again NAG got results. In early 1961, Glen Echo announced it would open to everyone.

“It got nasty after that,” Diamond recalls.

“HE SIMPLY WOULD NOT BE COWED”

As with the Greensboro sit-ins, he watched with outrage — and frustration at his own inaction — in 1961 when a mob in Alabama stopped the first bus of Freedom Riders. Someone threw a bomb. The bus roared with fire. Luckily, all on board escaped unharmed.

A call went out for more Freedom Riders. Diamond answered and joined a second group of buses in May 1961. “I thought it might be a long weekend, but it turned out to be two-and-a-half years,” he says.

Things quickly got tense. A law enforcement helicopter flew above. Alabama police cars drove in front of and behind the bus. At the state line, Mississippi patrol cars replaced them.

National Guard troops rode the bus to deter mob violence. “We were so stupid we didn’t realize the guard were the same people who wore Ku Klux Klan outfits when they were not on the bus,” Diamond says.

At Jackson, Mississippi, Freedom Riders were arrested and sent from jail to jail until they ended up at Parchman, the notorious state penitentiary. “We had no idea why they kept moving us, but the buses kept coming,” says Diamond, who spent about two months behind bars in Mississippi. “We started something.”

“I've been in situations where I've been frightened but didn't allow it to show.”

That same summer, Diamond faced death at close quarters. While he was picketing a Nashville, Tennessee, grocery store with Carmichael, police deemed both men ringleaders, possibly because of Diamond’s “irrepressible mouth. He simply would not be cowed,” Carmichael wrote in his autobiography.

The men shared a city jail cell. At 2 a.m., an intoxicated white guard approached the bars wielding a pump-action shotgun, which he loaded as they watched. The guard pointed the barrel first at Carmichael and then at Diamond, who told him, “Come on, you cracker so-and-so. Pull the damn trigger. … I’m ready to die.”

Horrified at first, finally Carmichael taunted the guard, too. “Pull the trigger,” he said.

The guard began trembling. He lowered the shotgun and slunk away.

The awestruck Carmichael concludes his story with an apt sobriquet for his cellmate. He dubs him “crazy-assed Dion Diamond.”

“I’ve been in situations where I’ve been frightened but didn’t allow it to show,” says Diamond. “I masked my fear.”

During the next three years, he would learn that, sometimes, even the best mask falls.

DISTURBING THE PEACE

After spending his spring semester behind bars, Diamond dropped out of college and joined SNCC, which sent him to Mississippi to organize voters. While in the town of McComb, he spent the night in a Black neighborhood by the railroad tracks.

While he was sleeping, a shotgun blast tore through the window by his bed, its pellets shredding the wall. When Diamond recounted that event in 2015 for a Library of Congress historian, he patted his belly and said, “If I’d had this girth then, a part of my body would have been shot off. That really made me realize the danger I was in.”

January 1962 found him in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, where police had used dogs and tear gas to disperse 2,000 students who walked out of classes at the all-Black Southern University. SNCC sent Diamond there to stage a second boycott.

The police had had enough. They arrested Diamond and charged him with multiple offenses, including disturbing the peace and criminal anarchy. “They said I was attempting to overthrow the State of Louisiana, and that’s true,” Diamond recalls. “If you get enough people to vote, you can change the Constitution.”

A judge raised his bail from $7,000 to $13,000. After four days in the jail’s general population, he was put in solitary confinement for about two months, presumably for his safety.

His cell measured six by eight feet. Lights blazed night and day.

From his “isolated dungeon,” Diamond sent a letter that Howard University’s newspaper ran under the headline “Diamond Was Still Cocky, Undefeated in 44th Day.”

“Just as the little Dutch boy attempted to plug the dike, it seems as if all proponents of the ‘old way of life’ (or death to some) have been called forth to stem the raging tide of freedom,” he wrote. “They realize that these tides are about to inundate the banks of the Southern way of life.”

During Diamond’s civil rights campaigns, police handcuffed him more than 30 times. Washington Area Spark

THE VOICE OF BLACK FOLKS

His NAACP attorneys appealed his conviction on the grounds that Louisiana’s law against disturbing the peace was too vague. As his case wound its way to the Supreme Court, Diamond, now free on bail, continued his get-out-the-vote work in Mississippi.

Hoping to recruit white students from the North to volunteer in 1964 for Freedom Summer, an expansion of SNCC’s efforts, Diamond in August 1963 attended the National Student Association Congress in Columbus, Ohio. His fellow Howard students were starting to graduate, and Diamond envied them.

By chance he found himself standing in a line next to a University of Wisconsin student who asked him about coming to Madison.

Knowing the UW was brimming with student activism, Diamond answered, “Hell, yes.”

Three weeks later, he enrolled at the UW and switched his major from physics to history. “Because of my civil rights exposure, I wanted to find out why it took 100 years from the Emancipation Proclamation for there to be organized protests,” he says.

Diamond remembers life in Madison as “very awkward” and like being in a “foreign country.” It was the first time he socialized with whites. “The only people of color were football or basketball players. Everybody tried to force me to be the voice of Black folks,” he says.

Soon he would remember his Wisconsin days with fondness.

“HIS FIGHT IS THE FIGHT OF ALL OF US”

Diamond lost his Supreme Court appeal. The court declined to hear his case, unanimously ruling that his writ of review had been “improvidently granted.” The New York Times said, “Some observers read into the case a clear warning to racial demonstrators in the South that there is a limit to what they can do within the shelter of the Constitution.”

Now required to return to Baton Rouge to complete his sentence, Diamond became well known on the UW campus. Students raised $254 to pay his fine and travel expenses. A Daily Cardinal editorial called him “part of the vanguard of those fighting for dignity, for a set of rights, for a part of that way of life which we as a people have denied him. … This student is one of a new breed; committed to a society where justice will be color blind. His fight is the fight of all of us.”

At age 22, in March 1964, Diamond again found himself in the general population of Baton Rouge’s city jail. He kept a diary about his two months behind bars that spans the spectrum of human emotion.

“Accused rapists, convicted thieves, and persons of every conceivable crime are my companions,” he wrote. “The drunks and the murderers are my cellmates. The hopeful and the hopeless, the degener- ate and the ‘saved’ are my sources of ‘intellectual’ stimulation.”

Elsewhere in the diary, thinking of his adopted state’s lakes, pastures, and rivers, he writes, “in the final analysis, however, I inevitably travel vicariously, of course, back to Wisconsin.”

The diary concludes with an entry written near the end of his sentence. The bars no longer hold him. In his soul he is free.

“Dear Someone, Anyone, Everyone!” the passage begins. “Within the last five minutes, while perched in a window which had vertical and horizontal bars, I discovered the meaning and the feeling of a breath of spring. … As the wind blew the drops through the open window, I stood there with the greatest most peaceful feeling. … Perhaps my spirits are being lifted.”

A GOOD RIDE

After serving his time, Diamond transferred to Harvard, where he completed his education. For most of his career, he served as a consultant to the Departments of Labor and Health and Human Services. Married for 52 years, he has a son, three grandchildren, and one great-grandchild.

With other Freedom Riders, he returned to Parchman on the 50th anniversary of his imprisonment and had his photo taken. It shows him defiantly standing in the open door of his cell. He has delivered lectures about his experiences to college students and military officers around the U.S. He recently volunteered with Meals on Wheels.

Diamond wonders if he has done enough. “I have a damn comfortable life,” he says. “I feel like the stuff I was fighting against, I have become.”

When reminded that his long-ago efforts helped a lot of people, he replies, “That was yesterday.”

Then he adds, “When I was a kid and even much later, I never thought I’d reach this age. It’s been a good ride.” •

Freelance writer George Spencer is a former executive editor of the Dartmouth Alumni Magazine

Published in the Fall 2024 issue

Comments

Malcolm Gissen September 24, 2024

As an alum of the UW Law School (’68), I am very proud of Dion Diamond and the incredible courage he demonstrated again and again in risking his life to stand up for the American Constitution. I spent the summer of my first year of law school in 1966 working with SCLC and the Lawyers Committee to integrate Grenada, Mississippi. In 1968, I started a program bringing Black children from Mississippi to live with families in rural Wisconsin. Over 3,000 Black kids learned that they were as good or better than white people from this program. It was the incredible courage of people like Dion Diamond that helped to break down the barriers that existed in the South far too long. He deserves enormous credit for helping to make the US a better country!