Leading the War on Obesity

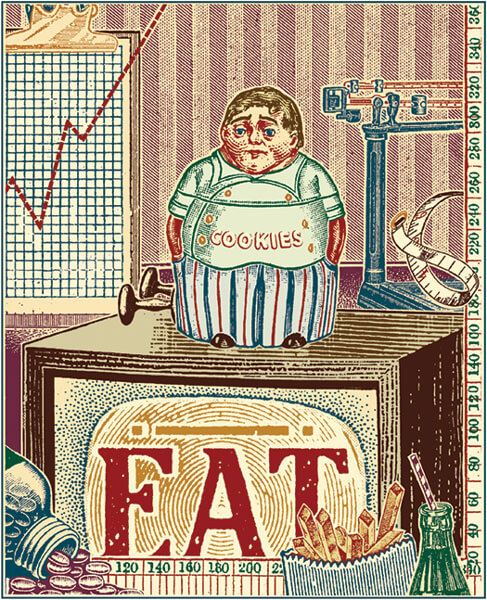

Barry Popkin sees the struggle against food policies and marketing practices that promote excess weight as nothing less than a battle for human rights.

When Wal-Mart announced its five-year, healthy food initiative in January 2011, First Lady Michelle Obama heaped praise on the corporation for joining her campaign against childhood obesity, saying it could potentially transform the entire food marketplace. Wal-Mart aims to reduce sugar by 10 percent, cut sodium by 25 percent, and eliminate industrially produced trans fats in its line by 2015. That’s quite a commitment by the world’s largest retailer.

However, Barry Popkin ’67, MS’69, one of the most respected and prolific voices about obesity and America’s food supply, challenged Wal-Mart to go even further. He believes that the retail giant’s market share gives it the muscle and the mandate to force other food makers to follow its lead. “If Wal-Mart says, ‘We want you to do it,’ it will happen,” he told National Public Radio.

This is classic Popkin — taking what many would consider a victory and pushing for more, a tactic that hearkens back nearly fifty years to his rabble-rousing days at the UW in the early 1960s, when UW students were among those leading the charge in the civil rights movement.

Now a professor of nutrition at the University of North Carolina, he credits his university experience and his several years of civil rights organizing after he left the UW for making him the activist and advocate he is today. Long before Jamie Oliver and Michael Pollan put our food supply and dietary habits on trial — when much of the nutrition focus was still on hunger — Popkin was warning of the coming obesity epidemic.

Nagging food manufacturers about the amount of saturated fat and added sugar in a bag of chips or a soft drink may seem like a comedown from the heady days of freedom-riding and shutting down the campus to protest the Vietnam War, but not to Popkin. He sees the food wars as the human rights battle of the twenty-first century, citing similarities such as going up against powerful, entrenched interests and trying to get them to do the right thing.

“I’m an activist in a different sort of way now,” he says. “I work within the system and with governments to make changes.”

These days, Popkin is on a cordial, first-name basis with many people in the very industry that he blames for the world’s obesity problem. But it would be a mistake to think that the one-time radical has been co-opted. In his most recent book, The World is Fat: The Fads, Trends, Policies, and Products That Are Fattening the Human Race, Popkin makes the case that our lifestyle and food system are at odds with millions of years of evolution and are guaranteed to make us even fatter. According to the World Health Organization, we’re in a situation that would have been unimaginable fifty years ago: the world’s population is rife with diabetes and hypertension, and overweight people outnumber undernourished people by more than two to one.

Popkin doesn’t believe this is simply the result of individual overindulgence, but rather the outcome of recent trends in technology, globalization, government policy, and food industry marketing practices. He sees a direct link between the ubiquity of fast, cheap, processed foods and the growing obesity problem. He says that while the prices of meat, dairy, and sugar are about 20 percent of what they were in real terms in 1950, the cost of beans, fruits, and vegetables has gone up.

The food crusader calls claims of “heart healthy” products by food manufacturers false advertising, and declares excessive red meat bad for global climate control and also for human health. He once claimed that soft drinks are linked to diabetes and obesity in the way that tobacco is to lung cancer. Such inflammatory statements have landed him in pitched — but respectful — battles with many in the food industry.

“Barry very much believes in improving public health, but we don’t necessarily see eye to eye,” says Rona Applebaum, Coca Cola’s chief regulatory officer. “We all want a healthy public and community, but Barry and I disagree on how to get there.”

Barry Popkin first became interested in global health issues as a Wisconsin student when he spent his senior year abroad. Courtesy of University of North Carolina.

One way to get there, says Popkin, is with what is commonly known as a fat tax. In the past three decades, caloric intake has increased on average by 150 to 300 per day, with approximately half coming from sweetened beverages. The proposal to tax sodas, other sugary beverages, and junk food is popular with scientists and health advocates, but goes over like a lead balloon with the beverage industry.

In 2010, then-New York Governor David Patterson proposed a penny-per-ounce tax on soda and other sweet drinks (assisted not only by Popkin, but also by his former students) as one way to close the state’s mounting budget gap. Months later, the initiative vanished, killed by a multimillion-dollar ad campaign launched by a group called New Yorkers Against Unfair Taxes. The campaign, funded by the beverage industry, labeled the plan as a regressive tax and a dubious health policy.

Having watched the same scenario play out all across the country, Popkin was disappointed, but not surprised. “I lose many battles, but you can’t see the problems we face — millions of diabetics, kids, and adults who are so overweight and they can’t walk — and not do something about it,” he says. “My economics and activist background has given me a special perspective on nutrition, and being shot at and beat up [as a civil rights organizer] has prepared me for dealing with controversy that comes with going up against the food industry.”

Born and raised in Superior, Wisconsin, Popkin arrived in Madison in 1962, when five hundred students picketed the Woolworth’s store on the Capitol Square in solidarity with Southern blacks. Wisconsin students marched on Washington with Martin Luther King, Jr., in 1963, protested nuclear testing, and were among the first students to protest the Vietnam War in 1964.

“I was a small-town kid with that perspective of the world,” Popkin recalls. “When I got to [the] UW, I experienced different influences and perspectives for the first time, and it completely changed my world view.”

Popkin joined the Students for a Democratic Society and Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. He spent his senior year as a UW student in India, living and working in the densely populated shantytowns of Old Delhi among horrendous sanitation and raging poverty. That experience became the genesis of his interest in health and welfare and the spark for his senior thesis on the economics of nutrition. He worked as a full-time activist for several years, believing that true social change could only be achieved by grassroots organizing.

In 1973, Popkin enrolled at Cornell to pursue a doctorate in agricultural economics, and he received his PhD in 1974. He spent the next three years studying nursing mothers in the Philippines as an economist at the School of Economics there and also as a consultant to the USAID Regional Development Office. Returning to the States in 1977, he joined the University of North Carolina faculty and built his life in Chapel Hill, the town that the late senator Jesse Helms famously labeled a zoo because of its liberalism.

“I had been involved in civil rights stuff [in Chapel Hill] and really loved it for that reason,” Popkin says, adding that the city is a liberal oasis “in the middle of an enormous hunk of reality in the South.”

More than thirty years later, Popkin’s appearance — tall, slender, bearded — and hobbies — biking and yoga — check many of the “aging hippie” boxes. His passion for causes has not waned or drifted far from his leftist roots, although he points out that he is not a Marxist or a Communist.

Popkin, who created the UNC Nutrition Transition Research Program, has traveled the globe to study the effects of dietary and physical activity patterns on health. He has published nearly four hundred peer-reviewed journal articles, is one of the three most cited nutrition scholars, has given hundreds of media interviews, been quoted in dozens of consumer publications, and racked up a slew of honors and research fellowships.

He noticed that, even in poor countries, people were growing fat. And as the people got bigger, they also got sick. Problems such as diabetes and heart disease began escalating among the poor — the very people who can least afford medical care or medicines.

“For five or ten years, nobody believed me,” he says. “It was like when we first started talking about the dangers of tobacco in the 1950s and ’60s.”

This gave rise to Popkin’s concept of nutrition transition — increased consumption of unhealthy foods compounded by an increased prevalence of overweight people in middle- to low-income countries. The phenomenon has serious implications for public health outcomes, risk factors, economic growth, and international nutrition policy. For instance, Popkin says, twenty years ago, the Chinese had virtually no weight problems compared to today, when a third of Chinese adults are obese and more Chinese kids than American kids are diabetic.

Popkin concedes that the human palate now desires sweet, fatty foods and drinks, but believes there is a way to make those foods more healthy and ultimately reduce the number of calories we consume.

In recent years, he has taken a less confrontational approach to dealing with the food and beverage industries by focusing on areas of agreement. In 2005, he assembled leading nutrition scientists to provide consumer guidance on the nutritional benefits and risks of a variety of beverages. In 2007, he started an annual Global Obesity Business Forum with senior executives from food, beverage, and infant formula companies to find a solution to the obesity epidemic.

Working with those in the food industry has not made him more trusting of their motives or hopeful about a good outcome, however. “This is like tobacco all over again,” he says. “There is nothing that happened with tobacco — hiring lobbyists, funding their own studies to confuse the public — that’s not happening with the soda industry.”

In June 2010, Popkin was appointed independent evaluator for the Healthy Weight Commitment Foundation, a consortium of companies that have set goals for making their products more health conscious. As watchdog, he will be looking over the shoulders of food giants such as Kellogg, General Mills, Kraft, and Coca-Cola, checking to see if they’ve done what they said they would do in two, four, and six years.

“Everything we do will be public and widely disseminated with press conferences, publications, [and] public documents on the web,” he says. “I will be tracking them.”

Melba Newsome is an award-winning freelance journalist based in Charlotte, North Carolina.

Published in the Spring 2012 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.