Fake News!

Thanks to UW alumni, the Onion birthed modern news satire, helping America to process its dysfunctions through humor.

In Funny Because It’s True: How the Onion Created Modern American News Satire, Christine Wenc ’91 compiled an exhaustive history of the Onion, the humor newspaper that began on the UW–Madison campus in the late ’80s. Wenc lived for a time in the same apartment as cofounder Tim Keck x’90 and was a copy editor, writer, and illustrator for the paper in its early years. Now an independent historian and editor at UW–Madison’s School of Education, she spent six years conducting “about a million interviews” for what she originally conceived of as an oral history. When Wenc ended up with way too much material, she switched to a prose history, which she published with the help of the Onion’s literary agent, Daniel Greenberg ’92.

In Funny Because It’s True: How the Onion Created Modern American News Satire, Christine Wenc ’91 compiled an exhaustive history of the Onion, the humor newspaper that began on the UW–Madison campus in the late ’80s. Wenc lived for a time in the same apartment as cofounder Tim Keck x’90 and was a copy editor, writer, and illustrator for the paper in its early years. Now an independent historian and editor at UW–Madison’s School of Education, she spent six years conducting “about a million interviews” for what she originally conceived of as an oral history. When Wenc ended up with way too much material, she switched to a prose history, which she published with the help of the Onion’s literary agent, Daniel Greenberg ’92.

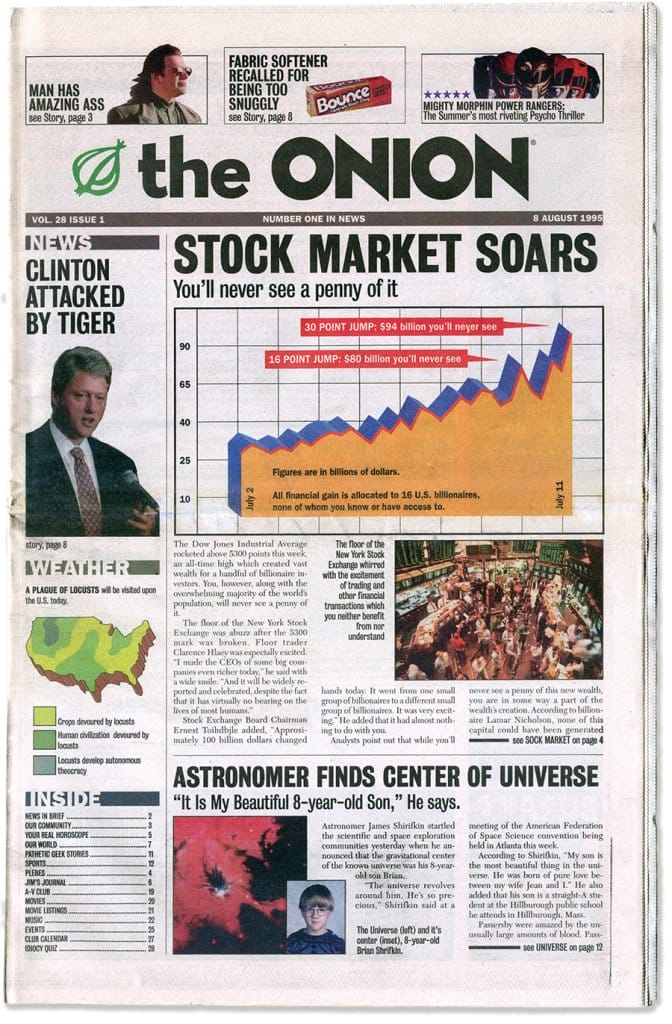

Wenc covers the paper’s evolution from a way to make money by students who had no idea what they were doing to a phenomenon that influenced today’s style of news parody. The Onion’s approach to making up the news is now ingrained in the nation’s psyche, to the point where people react to headlines that strain credulity by saying, “It sounds like an Onion story.”

Wenc engagingly captures the staff’s freewheeling chutzpah, which she attributes partly to ’90s slacker culture. When an advertiser asked to speak with the publisher, they had to look up what a publisher does, make up a name for their mythical administrator, and have someone posing as the publisher call back. Wenc also highlights the absurdly random nature of the staff’s early decisions, from the name of the publication to its very concept. But, seemingly by accident, the paper succeeded from the beginning.

As Wenc says, “A bunch of 20-something Generation X nobodies out in flyover country had invented something that would become one of the most culturally influential American publications of all time.”

This excerpt deals with the very early days of the Onion.

[In 1988, Tim] Keck decided to start his own newspaper. “I didn’t really have a good idea of what that was; I just knew I wanted to start a newspaper. I was going to quit school and do this newspaper. And then I met this guy in a history of science class, part of the Integrated Liberal Studies program at Madison. His name was Chris Johnson x’91.

“He’s one of those people that just has a weird light and energy around them. Completely fearless,” Keck says. “Can make a trip to the grocery store weird and uncomfortable and electric. He had this crazy childhood in Brazil and Poland and Sweden, and then he went to high school in Lodi, Wisconsin.

“When I met Chris,” Tim says, “I was like, ‘That’s the guy. I can’t do this on my own. I need somebody like Chris to do it with me.’ I talked to him about the idea, and he immediately jumped in.”

“A bunch of 20-something Generation X nobodies out in flyover country had invented something that would become one of the most culturally influential American publications of all time.”

Amy Reyer ’89 (Amy Bowles at the time, who would sell ads and write for the Onion in its first year) says, “Tim has a healthy dark streak that draws him to the most complicated, brilliant people. He’s genuinely curious about what makes someone tick. The weirder, the better.”

But then, out of the blue, not long after they’d started brainstorming, Johnson said he was going to drop out of school and move back to Brazil with his dad to work on a business venture. Tomorrow. He packed up his stuff and vanished.

Keck was shocked and bereft at the abrupt loss of his friend and purported business partner. At the same time, he was impressed by the boldness of it all. The disregard for convention. The hugeness of the move. He kept on working on the newspaper idea, but found he didn’t have the confidence to do it by himself. So he decided to go to Brazil on a cheap courier flight and convince Johnson to come back. He returned victorious and very hungover 10 days later. Johnson had said he would return in six months.

Keck had taken a room in my apartment around this time, and I remember him telling me about the newspaper idea when he got back from Brazil. He said they wanted me to be the art director, whatever that was. (Though I did do some drawings now and then, I actually became the copy editor.) I hadn’t met Johnson yet, but I was excited enough that I wrote about it in my diary: March 3, 1988.

Johnson finally got back to town, and then it was time to rock. “We didn’t have editorial ideas or anything complicated like that,” Keck says. “We just wanted to start a newspaper.” Keck’s mom loaned them $3,000, and they rented a [rundown] three-bedroom apartment on East Johnson Street, a few blocks from both State Street and the capitol, to be the office — and their home. The living room was the production and editorial area, and Andy Dhuey ’89 was brought in to live in the third bedroom and help pay the rent. Keck’s mom would also be their adviser.

The first problem was what to call it. The only requirement was that it couldn’t be serious. Maybe The Rag? How about The Paper? Then one day they were visiting Johnson’s uncle Nels, who lived in Madison. “We ate onion sandwiches a lot,” Keck says. “Why, I don’t know, but we did, and Johnson’s uncle said, ‘Why don’t you call it the Onion?’ ” Keck adds, “I’m sorry I don’t have an interesting story about why we called it the Onion; that’s it. We made a lot of snap decisions in those days.”

Reyer’s roommate, Pete Haise ’90, tells me, “And then I think somebody drew a pretty good onion, and that was the clincher.”

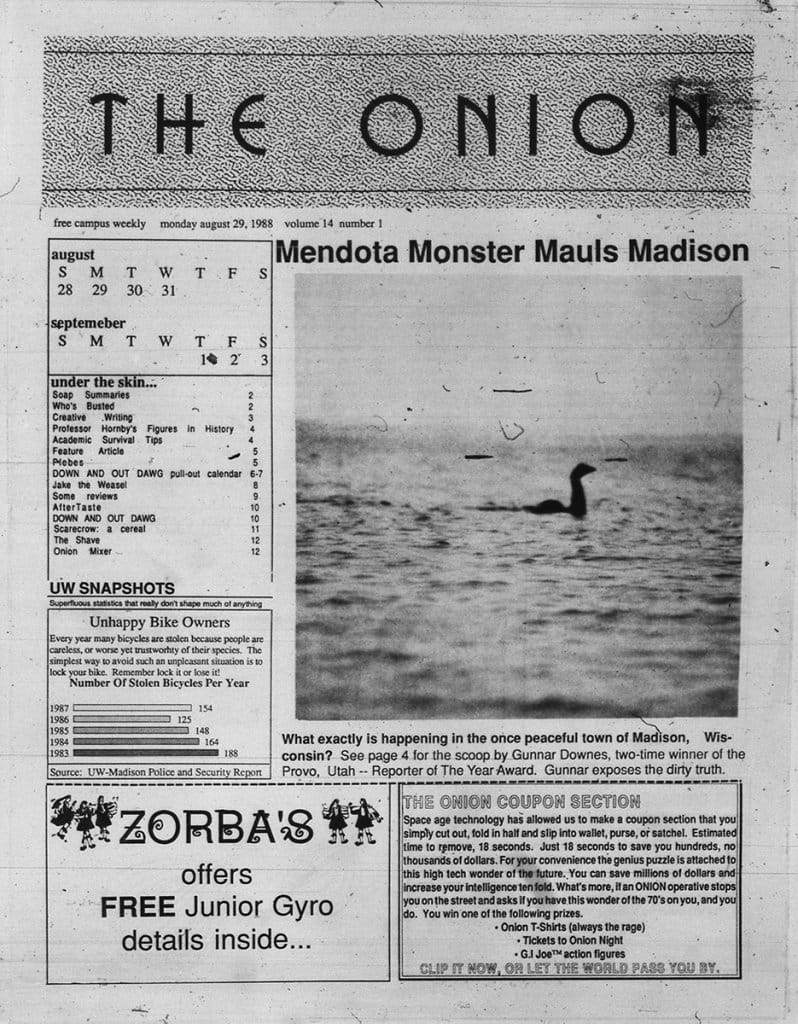

The Onion’s first issue, featuring Keck’s arm as the “Mendota Monster.”

Keck wasn’t sure how you charged for advertising in a newspaper, so he called “every publication in New York” to get their media kits. “A media kit is a thing that says how big ads are, how much the ads are, all that kind of crap. But I didn’t know any of that stuff. So I called New York Magazine, I called the New Yorker, I called the Atlantic, I called everybody. Nobody sent me anything except for the New Yorker.” Keck took the rate card, whited out the New Yorker, and put the Onion on it instead. (He left the rest the way it was.) Keck then called up his Dawg calendar advertisers, told them about his new project, and gave them the rate card. [The one-page monthly calendar had been illustrated with cartoons based on James Sturm ’87’s Daily Cardinal cartoon Down and Out Dawg and sold advertising. Keck had been distributing it to students and paying his rent with the proceeds.]

There would also be coupons on the bottom of the front page, he said. “They were all thrilled with me because of the coupon concept. Everybody loves coupons.”

Sturm agreed to let the new paper publish Down and Out Dawg. Keck also found another cartoonist he wanted to publish: Scott Dikkers x’87, the creator of Jim’s Journal. As Keck put it, “The Daily Cardinal paid them $5 a comic strip. I paid them $10.”

“So now we had some advertisers,” Keck said. “We had a name. We rented a Mac. This is in 1988, so it was a [primitive] little Mac, the ones where you had to put the floppy disk in and out and change it 80 times just to run a program. But we didn’t have any idea about the content in the publication.”

They had no editorial mission. No cause they wanted to promote. No message they wanted to send. They did love Spy magazine. Doing something in that spirit would be cool. But, otherwise, no topic fascinated them enough to make an entire newspaper about it.

As far as I know, only one other person from my high school class besides me graduated from UW–Madison, a guy named Todd Brown ’93. He was good-looking, funny, and charismatic, with parents from the Twin Cities. One day I went to visit him in his dorm during our freshman year, and he had a new friend there, a guy he’d met at the Ark Improv, a little independent theater a few blocks from State Street where he’d been taking classes and performing: Matt Cook ’89. Matt and I hit it off right away. He was from Chicago, he was really funny, and he was wearing a Joy Division T-shirt. We started hanging out all the time. That summer at a party at my first apartment, a tiny, sweltering attic two-bedroom on Conklin Place I shared with our friend Rachel [Johnson x’89], I introduced Keck to Matt Cook. Several of us were hanging out on the street — really an alleyway — waiting for Matt to show up.

“The first time I saw Matt Cook,” Keck said, “he was roller-skating with a refrigerator box on top of him down the street and then intentionally running into [stuff]. Like ‘Oh no! Oh no!’ and then ‘It’s okay, I’m okay!’ Like doing tons of pratfalls.” The box was so big it covered Matt completely, making it look like it was zooming around all by itself. He careened around bashing into things, and we all just about died laughing. Keck said, “Matt is really funny, and he’s self-hating, and creative, and not afraid to make a fool of himself. He kind of likes it. And that’s the ingredients of a great comedian.”

Keck says, “If there was a person who created the Onion’s voice, it would be Matt Cook.”

As the Onion evolved, stories became more political.

Brian Stack MA’88, who later became a writer and performer with Second City, Conan O’Brien, and Stephen Colbert, started his performance career at the Ark Improv in Madison. He told me that Matt Cook was in the first show he ever saw there. Cook joined other interesting performers from that era, like Joan ’84 and Bill Cusack. And also, “Chris Farley, the late great Chris Farley,” was there, too, “with his bandana and his Marquette rugby jacket.” Cook says, “I was Chris Farley’s first director. I taught him everything he knew about comedy except for cocaine and hookers and booze, because he learned that stuff by himself.”

Stack praises Cook and his creative style. “Matt was one of the most original thinkers I’ve ever met. He would do very, very fun experimental things with the Ark that were very conceptual and weird in wonderful ways.”

One day, Keck and Johnson asked Cook to meet with them. “It was this baby-businessman thing,” Cook said. The calendar had been pretty successful, Keck and Johnson said. Now they wanted to do a newspaper. Cook asked them what kind of newspaper, and they said that’s why they’d invited him to the meeting. “So sitting there at that time, at that very meeting, I said, ‘How about we just make it all up? Have all made-up stories, but play it like it’s a real newspaper?’ ”

“We’re gonna make up fake news. And people are going to believe it.”

Keck remembered that the Cardinal did an April Fools’ Day parody every year that was always really popular. “Well, I’m just gonna … do that,” he thought. The Onion would not be a real newspaper. It would be a comedic parody of one.

Keck and Johnson finally had their concept. They went to Reyer and Haise’s place and said, “Okay, we’re gonna unveil this thing. You’re sworn to secrecy.” (Their other roommate was Deidre Buckingham ’89, who became the photographer for the Onion in the first year. Buckingham, a skilled photographer and darkroom developer, told me that she had always wanted to be a photojournalist, but had flunked the skills test to get into UW’s journalism school because she couldn’t spell. The Onion became her outlet instead.)

Reyer says, “I didn’t even know them well enough to guess what it was. I was so sure it was gonna be lame.” They unveiled the concept and explained: “We’re gonna make up fake news. And people are going to believe it.”

They said it was going to be called the Onion, and Reyer said, “Please tell me that it isn’t like the onion has these deep layers of meaning. Is it just random?”

Johnson and Keck said, “It’s totally random. People will think it means something, but it doesn’t.”

“That was the beginning of it,” Reyer says. “And it actually was a big deal. It never felt like that at the time, though.” They asked Reyer if she wanted to help out, and she immediately said yes; she had a huge crush on Keck. She began selling ads, brainstorming, and eventually doing a little writing. Buckingham signed on, too.

Amy Reyer was born in New York City. When her family moved to Washington, DC, she attended the school Sidwell Friends. “It was a private school with some really smart kids,” she says. “And I did not feel like one of them.” For college, she wanted something completely different. “I thought, ‘I want to go to a Big Ten school. And I want to be anonymous.’ ”

Anonymity was important. Amy has a very famous older sister, Julia Louis-Dreyfus, a Second City and Saturday Night Live alum who had been working in film and would soon be cast in a lead role on Seinfeld. Amy’s younger sister is actress Lauren Bowles. Amy, the middle child, said she was a theater kid too. “But it’s not what I wanted to do. I was good at it, but it’s not what I wanted to do.” She was also tired of being in a small place — her Sidwell class was only about a hundred people — as well as “sort of being labeled as a dumb blonde” there. “That sucked,” she says. “It really sucked. And UW–Madison, when I visited, I thought, ‘Oh my God, this is so great. It’s, like, 85 percent blonde. Nobody will notice me. I’m just gonna be a regular person here.’ ”

Keck and Johnson asked Haise if he would sell ads. He said no. Though he used to do ad sales for the Cardinal, he was done with that. He had gotten fired from the Cardinal for skipping too many meetings. And he had other jobs now, including renting apartments and bartending. Whatever worked to keep him cruising. But after being asked “five times,” he finally caved, and within a few weeks he was the advertising manager.

Haise saw it as “rallying around a cause,” saying, “I never thought there could have been a better job.”

Haise was from Wauwatosa, a suburb of Milwaukee, a place for which he had great affection. His parents had divorced when he was young, and it may not have been a great time for him. Luckily, Haise was a very outgoing and social guy, and he had his hometown to give him a foundation even if his parents were not together. At the time, I saw him as this sort of surfer-dude Deadhead. According to Reyer, he was “baked all the time.”

The first issue of the Onion came out in the fall of 1988, with the front-page story “Mendota Monster Mauls Madison,” written by Matt Cook under the pseudonym Gunnar Downes (they wanted the most macho-sounding name possible), about a mythical lake monster named Bozho. The purposely blurry photo by Deidre Buckingham showed the head of the “monster” breaching the water. It was actually Tim Keck’s arm with a stocking over it; Photoshop had not been invented yet. (I remember seeing him at the office afterward and asking why he was all wet.)

The rest of the issue was a pretty anarchic mix of stuff. Most of it was written in the week or two before the first issue came out. In addition to copyediting, I wrote occasionally that year too; in the first issue I have a little story of the sort that would later be called “flash fiction.” We also published a story by a creative writing friend of mine.

The issue included excerpts from the campus police blotter — gossipy content that people would want to read, but that you didn’t have to pay for. Lorin Miller ’90 and Sandra Schlies ’90 wrote soap-opera summaries, which turned out to be one of the main reasons people picked up the paper. To create some buzz before the first issue hit the streets, Keck and Johnson printed out stickers with the Onion’s name and the motto they’d invented, “Witty, Irreverent, and a Little Nasty,” and stuck them up around town.

Keck said, “And it was just a pile of crap. When I saw it, I was like, ‘This is really, really bad.’ But strangely, it was successful. Like, right off the bat.”

A student at Madison at the time, future Onion writer Joe Garden x’92, said, “I remember being kind of impressed by it because back in those days, you had the regular alternative weekly, you had the socialist weekly, you had the feminist weekly. You had a second socialist weekly. The music weekly. You had all these free papers everywhere. And the Onion, even as raw and primitive as it was with the ‘Mendota Monster’ issue, it stood out from the rest of them.”

In only 10 months, Keck and Johnson had made the Onion out of nothing into a highly popular campus presence.

Excerpted from Funny Because It’s True: How the Onion Created Modern American News Satire by Christine Wenc. Copyright © 2025. Available from Running Press, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Published in the Fall 2025 issue

Comments

John Knox September 6, 2025

The early days were awesome. Worm Boy, the cosmic human fingerprint-in-space discovered by the Hubble Space Telescope that could *not* have been due to somebody touching it on the ground. To be a grad student at the UW in those days (I arrived the same week The Onion began) meant that you were never lacking for something to tape onto your office door. Tu stultus es!

eric September 9, 2025

Was in graduate school at the time (84-90) and please to say I remember the Onion and Madison’s madness. Happy they have gone global. The best things often come out of “nowhere” and then move to the big city.

Jay Badger September 9, 2025

Funny thing. I went upstairs to the Onion office thinking I could add my writing skills and goofy humor to the pot.

The door was unlocked and when I went in, nobody was there. We’re talking 88/89. I took it as sign, and never tried again.

Sorry to have missed out..