Paper Magic

Michael Velliquette MA’99, MFA’00 transforms a humble medium into stunning art.

Paper, scissors, rulers, and glue — Michael Velliquette MA’99, MFA’00 has built an international reputation working with materials you’d find in any school classroom. Although his mundane tools have a cozy familiarity, the magic Velliquette conjures with them will take your breath away.

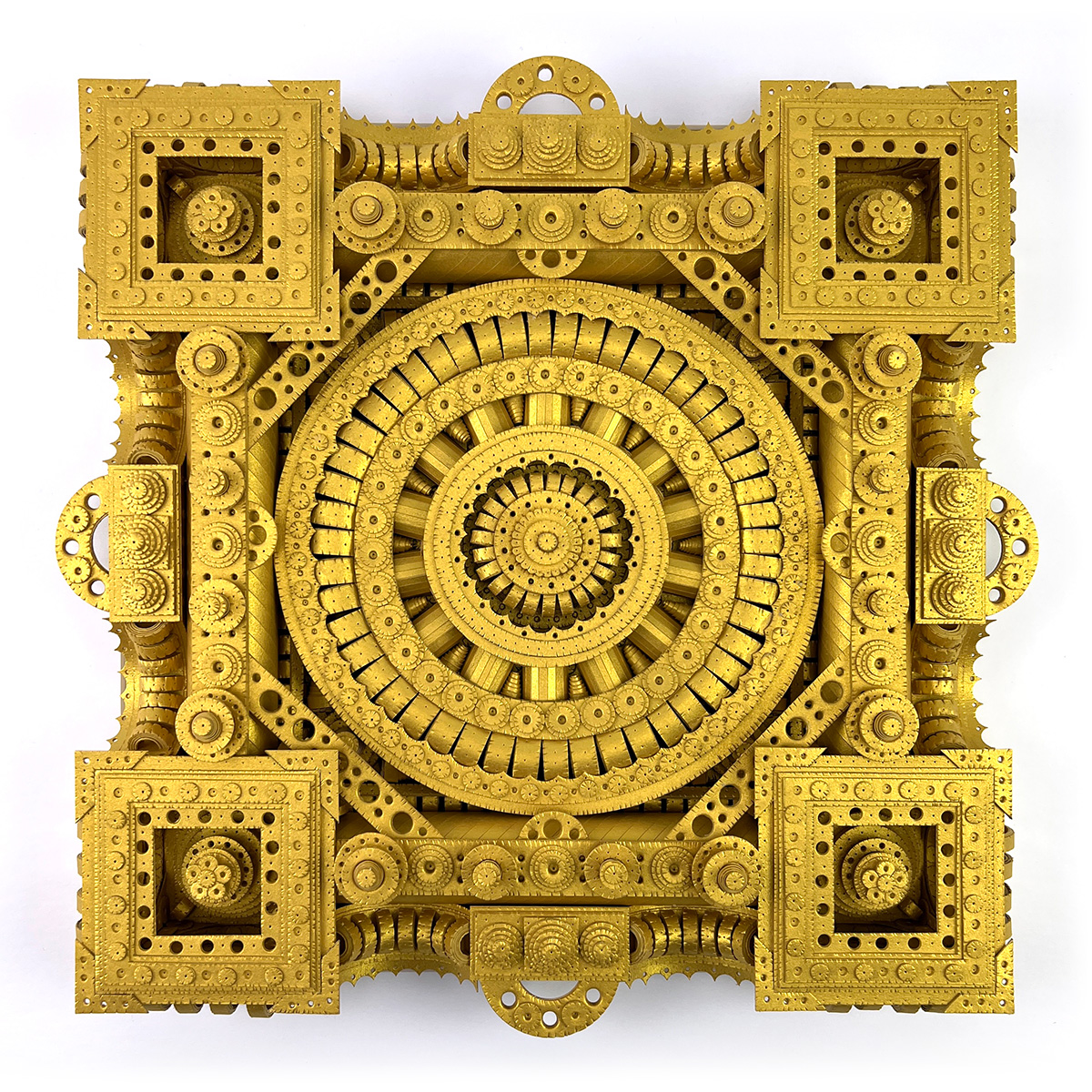

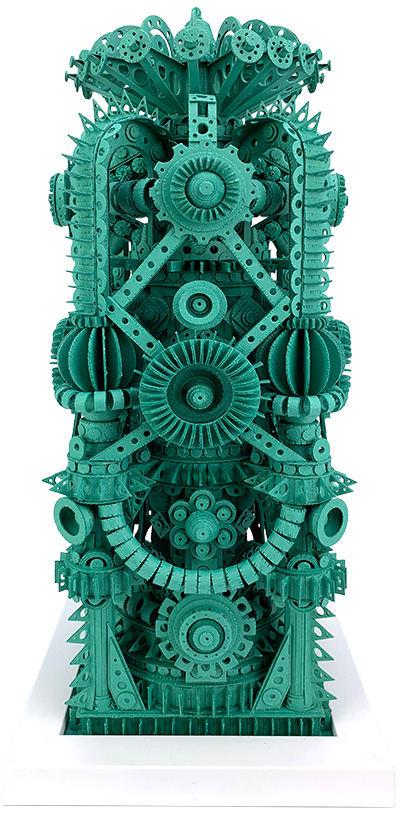

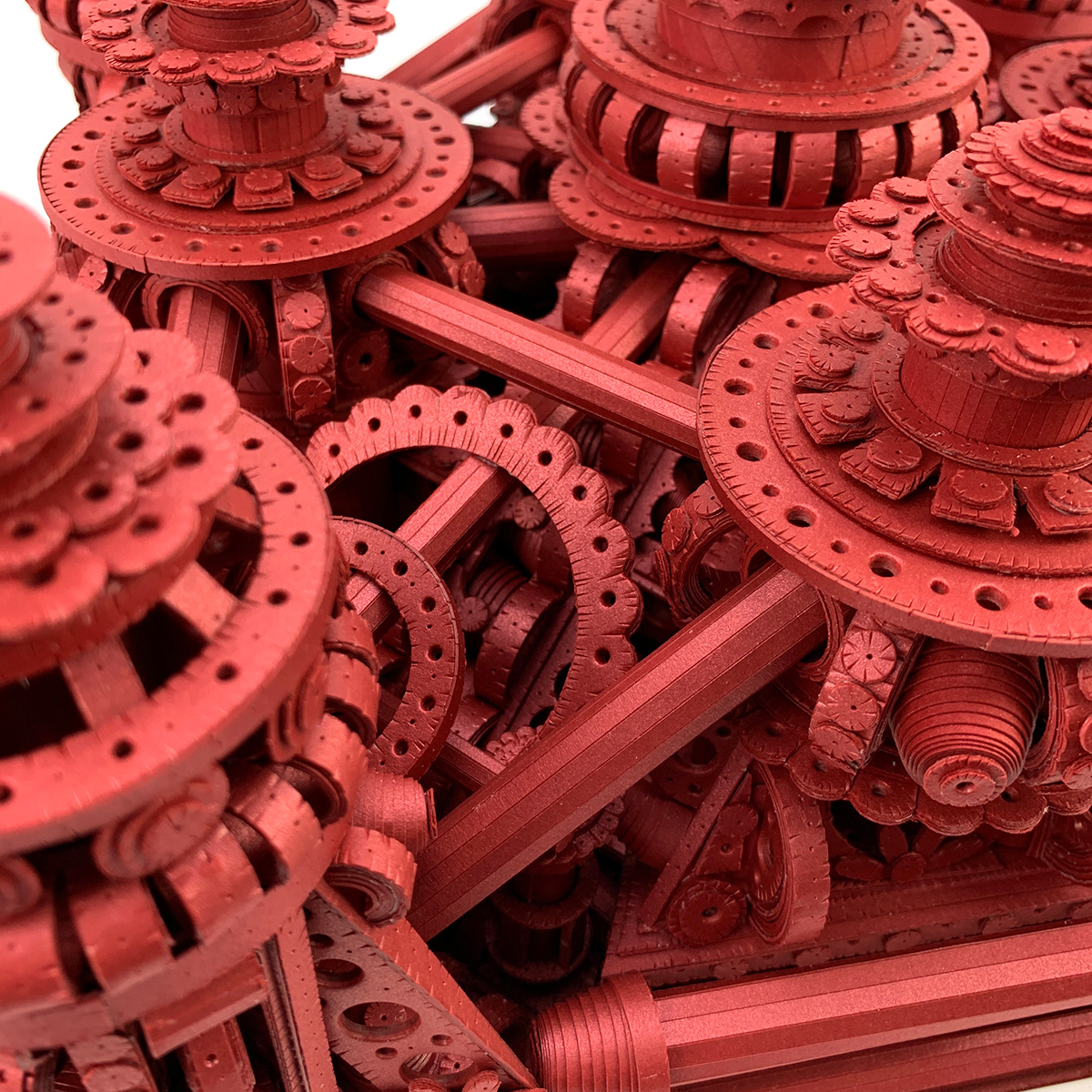

Over the past 20 years, the UW–Madison assistant professor of art has shaped paper and cardstock into room-sized installation pieces, brilliantly colored collages, and densely patterned constructions that evoke mandalas, clockwork, and architectural models.

In his paper sculptures, Velliquette leaves “no flat surfaces and not one spot unembellished, even in the spaces invisible to the viewer,” writes essayist Wendy Atwell in a 2020 catalog of Velliquette’s work. “He spends anywhere from 300 to 500 hours to make each one. He cuts around 5,000 pieces of paper that he rolls, stacks, and glues together, using a variety of techniques.” These techniques include the ancient arts of Chinese quilling and Japanese kirigami, which uses folding and cutting to make 3D objects.

Velliquette’s years of patient, focused exploration have resulted in some of the most ambitious, awe-inspiring pieces ever created with paper and glue.

From Performance Art to Paper

The artist’s dedication to paper evolved through chance and circumstance, a winding path almost as intricate as his sophisticated sculptures. As an undergraduate at Florida State University in the 1990s, Velliquette focused on performance and installation work. But as a student artist intent on creating performance environments, he needed affordable materials that were easy to source, deconstruct, and store. These early set pieces, which survive only in photos and video, were made largely with cardboard, paper, fabric, and paint. Loose and improvisational, they convey themes of discovery and play.

“My BFA was such a rich, wonderful experience,” Velliquette recalls. “I went into college not even thinking that art was an option, and I left so passionate and clear about what I wanted my life to be.”

After taking a few years to travel and work odd jobs, he applied to UW–Madison for graduate study, still committed to performance and installation. Laurie Beth Clark, a professor in the art department, was his earliest advocate, sharing her video library and her knowledge of performance art history.

After Velliquette came out as gay, his work increasingly focused on queer identity. “I was creating characters in otherworldly environments that suggest the figure is on some sort of journey of discovery, although you never quite knew who it was or where it was going.”

With Clark’s encouragement, he began systematically documenting these performances and soon found a receptive audience for his videos on the international lesbian and gay film festival circuit. For a graduate student, this was a tremendous vote of confidence.

Velliquette is “incredibly talented in his own work, but he understands and sees connections between contemporary artists and the papercraft traditions of the past.”

Virginia Howell, director of the Robert C. Williams Museum of Papermaking

After graduation, Velliquette took a job as a videographer on a cruise ship, and in his free time, he used the ship’s video equipment to explore new characters, costumes, and stories. While he describes this experience as an important period of self-exploration (the actual work, he says, was “terrible”), a subsequent move to San Antonio, Texas, proved much more fruitful. There he found teaching gigs at local colleges, a shared studio space, a community of fellow artists, and opportunities to design several room-sized installations.

“Studio work was sporadic,” he says. “I made quick art with lo-fi materials assembled aggressively with layers and layers of ornamentation. There was a sense of urgency to what I made, aggravated by the manic bursts of time I spent in the studio that doubled as my bedroom.”

Giant Eyeballs and Goofy Monsters

Velliquette’s first cut-paper works are vivid pictorial images, fantastic landscapes of waving grasses and seas of fire populated with tiny figures, outstretched hands, and giant eyeballs. Goofy monsters peek out over walls or between ocean waves; bright rainbow hues offer hope, countered by falling drops of blood or tears. Lovingly detailed and brilliantly colored, these apocalyptic dramas would be unnerving if they weren’t so beautiful.

Velliquette also explored simpler compositions: single blooms and still lifes, lively cartoonlike creatures, eye-popping colors, sharp outlined shapes, and passages of delicately scissored texture. A rich repertoire of motifs and basic forms — eyes, hands, profiles, stars, serpents, and more — recurs throughout Velliquette’s work, and he has returned over and over to comical, lumbering beasts that sport huge eyeballs, toothy mouths, and lolling tongues.

During a 2009 Arts/Industry residency at the Kohler Company in Wisconsin, he imbued these creatures with new dimension by creating beast figurines in porcelain. Charmed by the little 3D figures, Velliquette decided to try using paper to make sculpture. He had already been pushing the limits of paper collage by layering shapes, gluing spiky blossoms into place, and curling thin strips into loops and ribbons, but this was an entirely new direction.

Rather than building an image up from a sheet of paper, he began using heavier cardstock to form fully three-dimensional beasts, totemic abstractions, and large towers. Through trial and error, Velliquette learned what worked and what didn’t. His paper beasts gradually grew shaggier, stranger, and much larger in scale; the totemic forms and abstract symbols stretched into ever more eccentric and elongated profiles; and his virtuoso towers rose as high as 12 feet.

The drama, humor, and nerve of these ambitious works caught the attention of critics and curators, and they cemented Velliquette’s reputation as one of today’s most innovative paper artists. According to Virginia Howell, director of the Robert C. Williams Museum of Papermaking in Atlanta, not only is Velliquette “incredibly talented in his own work, but he understands and sees connections between contemporary artists and the papercraft traditions of the past. He’s a fantastic advocate for paper and is able to share why this humble material is so important to work with.”

Velliquette’s expanded technical repertoire informs every aspect of his studio practice, from new site-specific works and reliefs to public art pieces. Starting in 2010, his schedule of exhibitions, commissions, residencies, and teaching opportunities became filled to capacity.

Monochrome Masterpieces

It rises up in wordless gentleness and flows out to me from the unseen roots of all created being, 2021

Then came the pandemic, and Velliquette’s pace slowed way down. He spent a lot of time alone in his serene studio in downtown Madison, an orderly inner sanctum that thrums with creative energy and a sense of deep calm. With no looming deadlines or professional commitments, he found he had time to “just play and take as long as I wanted on a piece.”

His meditation practice was also deepening, and those hours of concentrated focus supported his ability to slow down, lavishing hours of attention on a single piece. As Atwell writes in her catalog essay, “Using his intuition and concentration, he builds up the forms that often involve repetitive tasks such as cutting the same shape 1,000 times.” The work that emerged from this period is strikingly distinct in his portfolio: monochrome, mandalalike abstractions that pair dizzying complexity with a profound sense of quiet. They invite a kind of devotional attention from the viewer.

Velliquette spends anywhere from 300 to 500 hours to make each of these intricate paper sculptures, cutting some 5,000 pieces of paper that he rolls, stacks, and glues together. The works have fanciful titles such as the one above: The fullness of experience in the emptiness of awareness, 2022

Velliquette starts with a symmetrical, four-fold structure, building out from the center in a series of improvised moves, each decision laying a path for the next. The repeated layers of simple shapes, the cut and pierced textures, the play of light and shadow, and the mystery of the interior spaces combine to create an ineffable whole. They evoke a sense of hush that seems worlds apart from the boisterous, polychrome excitement of Velliquette’s earlier work. These pieces demand a wildly impractical amount of time — he can only complete two or three in a year — but Velliquette has great appreciation for what he’s learned from this slow, meditative process.

“The looking experience happens in the mind; the eyes are just the tool, the mechanics to get it there,” he says. “I talk to my students about this a lot. It’s really an intimate experience, because you’re essentially putting something directly into somebody’s mind, that most intimate space.”

Passing on the Magic

Velliquette’s art class for non-majors draws close to 500 students per year in 30 sections. Among his stellar “Rate My Professor” comments is this one: “He was probably the best instructor I have ever taken a class with.”

Teaching has been a constant thread throughout Velliquette’s career, from his sojourn in Texas to his current position as assistant professor of foundations in UW–Madison’s Department of Art. His first Madison gig was in 2005, when Clark invited him to teach a summer session on video production for artists. That summer he met his now-husband, UW chemistry professor Tehshik Yoon, and it soon became clear Madison would be his home. He began teaching more courses for the Art Department, and in 2009, he offered the first art class for non-majors.

Considered an experiment in the beginning, the course started with 20 students; it now has close to 500 students each year in 30 sections. His foundations courses — Drawing Fundamentals, 2-D Design, and 3-D Design — are an integral part of the art curriculum, and he places great importance on professionalism, careful documentation, and a disciplined studio practice — lessons first learned at the UW that have served him well as an artist.

“Michael is a great teacher, but he’s also been one of the leaders in our department in thinking about teaching,” says fellow UW art professor Michael Peterson MA’91, PhD’93. “He’s been central to reworking our foundations curriculum. Our teaching is immensely stronger for his efforts.”

Velliquette’s current focus is a series of bright gold reliefs that combine layered, kaleidoscopic texture with the playful, iconic imagery from his earlier paper work: open palms, teardrops, giant eyeballs, and beasts. He uses these simple elements to conjure a sense of infinite space, a glittering, dream-like realm of symbols, shapes, and color. Immersive, expansive, and unabashedly beautiful, these mature works radiate peace, hope, and possibility.

“Ultimately,” Velliquette says, “my work is about creating an experience that’s uplifting, to elevate a sense of happiness and kindness in the mind of the viewer.”

Jody Clowes is a curator, writer, and director of the James Watrous Gallery in Madison.

Published in the Summer 2025 issue.