New Center Will Explore UW’s Past

The project builds on the acclaimed Public History Project.

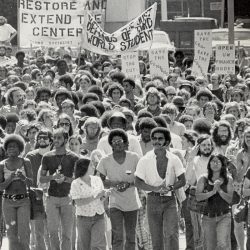

The Sifting and Reckoning exhibition at the Chazen Museum gave voice to those who experienced and challenged bigotry. Bryce Richter

UW–Madison will establish a permanent center with full-time staff to continue and expand on the work of its well-received Public History Project. The new entity, to be called the Rebecca M. Blank Center for Campus History, will be devoted to educating the campus community about the university’s past in ways that will enrich the curriculum, inform administrative decisions, and bolster efforts to achieve a more equitable university.

Late chancellor Rebecca Blank commissioned the Public History Project in 2019 as one of several responses to a campus study group that investigated the history of two UW–Madison student organizations in the early 1920s that bore the name of the Ku Klux Klan. The project was charged with giving voice to those who experienced and challenged bigotry and exclusion at UW–Madison and improved the university through their courage and actions.

The project’s museum exhibition, called Sifting and Reckoning: UW–Madison’s History of Exclusion and Resistance, ran last year at the Chazen Museum of Art.

“Students and alumni alike told us that visiting the exhibition made them feel more connected to the UW,” says LaVar Charleston MS’07, PhD’10, deputy vice chancellor and chief diversity officer. “They saw themselves and their communities being reflected in the history of the university — in some cases for the first time.”

John Zumbrunnen, vice provost for teaching and learning, says many instructors across campus have incorporated the findings of the Public History Project into their courses and expects this practice to grow.

Published in the Summer 2023 issue

Comments

George Gonis July 12, 2023

A sidebar in On Wisconsin’s summer 2023 issue offered that instructors across campus are starting to incorporate into their courses findings presented by the UW’s recent Public History Project — stories of Badgers throughout the decades who experienced and challenged bigotry and exclusion, stories that now will also be part of the new Rebecca M. Blank Center for Campus History. Rescuing and preserving every inch of that difficult past is vital indeed.

UW officials, the sidebar added, expect the practice of classroom instructors embracing and using these rediscovered stories — all born of the Public History Project — to be a growing one. Surely one of the recovered stories these instructors should be sharing in the years ahead entails finally setting the record straight on the towering racial-justice record across seven different decades of Badger alum and Hollywood icon Fredric March (class of 1920) — a praiseworthy and riveting narrative inextricably linked to the very creation of both the Public History Project and the Rebecca M. Blank Center.

The need for UW instructors to present March’s immoveable lifelong commitment to racial justice has been a notion echoed publicly and wholeheartedly these past five years by scores of revered and progressive historians and civil-rights heavyweights — from the national headquarters of the NAACP to The Progressive magazine to legendary activists Dr. Clarence B. Jones and Dr. Bernard LaFayette to Langston Hughes biographer Arnold Rampersad to the descendants of Lena Horne, Whitney Young, Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee, Will Geer, James Baldwin, Ambassador Andrew Young and the Hollywood Ten, just to name a few.

A gathering collection of acclaimed civil-rights authors and academics across the country have reminded us that March (1897-1975) — a 30-year intimate ally of the NAACP and a man Smithsonian Secretary Lonnie Bunch recently called “one of the great liberals of the 20th century” — regularly risked his career and his very life in Jim Crow America battling bigotry, antisemitism, Nazism and white supremacy. And that inspiring story needs to be proudly shouted and celebrated across Badgerdom.

George Gonis ‘79

Milwaukee

Dawn Ellison, MD July 14, 2023

Sounds like a much needed project. I hope that UW will right the wrong done to it’s own anti-racist Fredric March and recognize his tireless work. An error was made. Let’s accept that and give this man credit!

Lisa Kildahl Highet July 25, 2023

Congratulations UW on the Rebecca Blank history project with its goal of finding the truth and educating the campus about the university’s past. As a new student fresh from New York in the 1970’s, I looked for friends and causes through various campus groups, much like Fredric March did; trying new things, joining and quitting. March quit a group, then devoted a lot of his busy life to fighting bigotry and racism, and now his his name is no longer on the theater I frequented. We all make mistakes. Fredric March was not perfect, but he was a model citizen, a famous and talented human who set an example for generations of Badgers to come. I believe UW and the Blank Center would set a great example by restoring March’s name back where it belongs.

George Gonis July 27, 2023

As the the post just above from New Yorker and fellow Badger Lisa Kildahl Highet suggests, the legendary UW alum and racial-justice icon Fredric March would be a staunch and outspoken advocate on behalf of the mission driving the new Rebecca Blank Center for History. Happily, by the tone of her post, Ms. Kildahl Highet is rightfully and clearly a Fredric March ally and clued into March’s decades on the front lines of civil rights, but allow me to pass along here a gentle correction — one which will very likely make her (and all progressive, fact-embracing Badgers) feel even prouder of Mr. March’s unimpeachable, lifelong activist record.

As many writers, academics and other historians have pointed out in articles published these last three years in several progressive national media outlets, here are the three key things people need to know about Fredric March’s presence his senior year in a group yearbook photo depicting members of an organization sporting the KKK name.

1.

March’s group was an honorary for outstanding academic juniors founded around 1916 at the University of Illinois — naively named years before anyone knew about the actual Klan that murdered, terrorized, violently promoted hate and took over assorted state governments beginning in the 1920s. In 1916 at the University of Illinois — and in autumn 1919, when this junior honorary first came to Madison — virtually no one in the United States had even heard of the so-called “Second Klan” that was about to terrorize the nation. That repugnant group (known only, at the time, in just a handful of counties in Georgia and Alabama) didn’t make its “Invisible Empire” presence known to the rest of the country until 1921-22. Moreover, March did not (and could not) “join” the unfortunately named junior honorary — and he had absolutely no agency whatsoever in becoming part of the honorary. In fact, he had never even heard of the honorary — nor did he ever search for it on his own. It was foisted upon him, if you will — and for one very good, very benign reason: As purely an honor society — again, an import from the University of Illinois, making its very first appearance on the UW campus in the 1919 autumn semester of March’s senior year — members came into existence only through surprise inductions suddenly thrust upon a select few chosen solely for their stellar academic record. Accordingly, March could not “pursue” membership in this society or just decide to join it “off the street.” And the group itself subscribed to no causes of any kind. Indeed, the KKK academic honorary inducting March worked the way most campus honoraries and honor societies work across the country: surprising their brand new members with an induction out of the blue. For example, no one joins or can join Phi Beta Kappa — Phi Beta Kappa finds YOU if it judges you to have sufficient grades and campus accomplishments.

2.

Relying completely on primary sources, an array of progressive historians have on several occasions confirmed (across the last dozen or more years) that this strangely and unfortunately named UW student honorary had absolutely NOTHING to do with the actual Klan or that group’s horrifying and repugnant goals. For example, we even know of Daily Cardinal editors who were inducted into the KKK academic honorary and who also wrote editorials condemning the actual Klan.

3.

Accordingly, Fredric March made no “mistake” in agreeing to accept the surprise induction and invitation awarded by said honorary — one of many campus honoraries across March’s college career recognizing his outstanding accomplishments at the UW. There was no youthful indiscretion. He didn’t quit — or have to quit — the group because there was no moral dilemma (related to race or otherwise) compelling him to do so. It’s also important to note here that champion high school orator March was delivering anti-white supremacy speeches when he was 13 and that his senior year in Madison saw March begin an intimate 48-year friendship with world-renowned UW professor (and acclaimed racial-justice warrior) Max Otto. When the real KKK did first start to make itself known across the nation beginning in 1922 (two entire years after March received his UW diploma), UW and University of Illinois members of March’s old honorary were mortified that people were now starting to confuse their utterly benign honor society with the terrorist racist organization and its hateful goals. Accordingly — and virtually immediately in 1922 — student members of the group enthusiastically, quickly and completely rid themselves forever of the honor society’s KKK moniker, choosing instead, for its name, the utterly inoffensive Tumas.

Hope this helps clear up any misconceptions or misapprehensions.

George Gonis ‘79

Milwaukee

Lisa Highet July 28, 2023

Appreciated your second post here, Mr. Gonis. Wonderful to hear. Even better news about Fredric March! Thanks for taking the time to set the record straight. March’s decades of passionate work on behalf of racial justice just get more and more impressive as new facts continue to come forth telling us of a commitment to civil rights that stretches back to the actor’s early high school years.

I hope the new Rebecca Blank Center for Campus History — in its mission to give a full accounting of UW’s proudest and lowest moments in the long journey to equality — does see its way clear to sharing these salient facts about March, especially in light of UW’s confounding and continuing failure to rectify its terrible decision to remove March’s name from Memorial Union’s Play Circle.

It seems to me that to be true to its stated mission of “sifting and reckoning,” the Center must necessarily share not only the story of March’s lifelong civil rights activism, but the gory details of the March name removal, too. And speaking of reckoning, stripping his name and allowing March to be irresponsibly and falsely branded on campus as a white supremacist and Klan member certainly seem like injustices that deserve to be reckoned with.

If that honest reckoning doesn’t happen, then the UW is no longer the university I chose as a New York high-schooler in the 1970s because of its progressivism. On the contrary, it would remind me more of today’s Florida, now transformed into a murky backwater state whose leaders are setting it back 100 years. And so I say to UW now what I would say to Florida: get your facts right; we all have an obligation to right the wrong! Again, as a champion of civil rights, Fredric March’s name should be restored to the Play Circle or given “full shrift” in the new Center for History. Only when UW does the right thing will I believe it should be considered the progressive academic institution it once was.

Lisa Kildahl Highet