Looking Back to Move Forward

UW–Madison grapples with the prejudice in its past.

For years, friends and family members have given Charles Holley ’88, JD’91 gifts of clothes and other items with the UW logo on them. His children, he says, are always a bit perplexed by his muted reaction.

In reality, Holley’s thoughts about UW–Madison are mixed. He met terrific friends on campus and received a great education, he says, but he also remembers regularly being called racial slurs on State Street at bar time and watching a fellow Black student pack up and leave school after being aggressively harassed because of his race while walking to his dorm. The administration, he says, didn’t seem to care very much.

Recently, when a researcher with UW–Madison’s Public History Project contacted Holley to discuss his time at the university, he agreed to sit for an oral history interview, intrigued by the prospect. As he shared his experiences as a student of color on a predominantly white campus, he appreciated the opportunity to have an extended discussion about complex issues.

“They really wanted to hear from me in an in-depth way,” says Holley, a Chicago attorney.

Since fall 2019, researchers with the Public History Project have completed 140 oral history interviews with alumni and current students. They’ve dug deep into the university’s archives, scoured decades of media coverage, and read 168 volumes of the Badger yearbook and the Daily Cardinal.

The effort is intended to give voice to those who experienced and challenged prejudice on campus. Over the past three years, the project’s researchers have shared their findings through campus presentations, special events, and blog posts.

The project will culminate this fall with an exhibition at the Chazen Museum of Art and a companion online gallery and archive. Spanning more than 150 years, Sifting & Reckoning: UW–Madison’s History of Exclusion and Resistance (September 12–December 23) will make space for the university’s underrecognized and unseen histories. The title plays off “sifting and winnowing,” the iconic phrase that has come to represent the fearless pursuit of knowledge at UW–Madison.

“Reckoning is an active, participatory process, and that’s so important when thinking about this project,” says Kacie Lucchini Butcher, the project’s director. “We have to know this history and grapple with it — even if it’s uncomfortable and hard to face — because that’s part of making the university a more equitable place.”

The challenge was to figure out how best to approach this sensitive subject.

“How can a university call itself a center of learning if it is not fully honest about its own history?”

A Clean Break

The project has roots in the university’s response to the 2017 white supremacist rally that turned violent in Charlottesville, Virginia. In the wake of the tragedy, UW–Madison chancellor Rebecca Blank denounced the ideologies of all hate groups and said it was time to confront racist elements in the university’s past and make a clean break with them. She appointed a study group to look at two student groups that bore the name of the Ku Klux Klan around the 1920s.

One of the groups, a fraternity house, was found to be affiliated with the National Knights of the Ku Klux Klan. The other, an interfraternity honor society composed of student leaders, had no documented connection to the national KKK and no known racist ideology. Its name remains inexplicable.

In compiling its report, the study group identified a broader pattern of exclusion. It concluded that the history the UW needed to confront was not the aberrant work of a few individuals or groups but a pervasive campus culture of racism and religious bigotry that went largely unchallenged in the early 1900s and was a defining feature of American life in general at that time. Blank commissioned the Public History Project as one of several responses.

“The study group’s findings pointed to a need to build a more inclusive university community through an honest reckoning with our past,” Blank said at the time.

A MORE WELCOMING CAMPUS

UW–Madison has taken many steps to make sure every student feels safe, respected, and welcome on campus. Among recent efforts, the university:

- Created, in partnership with the Wisconsin Foundation and Alumni Association, the Raimey-Noland Campaign to fund diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts across campus. Learn how you can support the campaign here.

- Launched the Our Wisconsin inclusion education program and made it a requirement for all first-year and transfer students.

- Pledged a future of cooperation and collaboration with the Ho-Chunk Nation and other First Nations of Wisconsin through the Our Shared Future effort.

- Opened identity centers for Black students, Latino students, and Asian Pacific Islander Desi American students.

- Increased the number of faculty of color from 446 in 2016 to 580 in 2021. Between 2012 and 2021, enrollment of students of color increased by 60 percent while overall student enrollment rose by 12 percent.

The project comes as the university seeks to make sure all members of the campus community feel welcome and respected. A first-ever campus climate survey in 2016 found that historically underrepresented and disadvantaged groups, while reporting generally positive experiences on campus, consistently rated the climate less favorably than students from majority groups. The survey was repeated last fall with similar findings. Both surveys also revealed that students value diversity and that it’s important to them that the university does, too.

The Public History Project is uniquely suited to advance this goal.

Putting History to Use

Lucchini Butcher describes public history as an approach that seeks to elevate the stories of community members — especially those previously ignored or discounted — and share them in accessible, pragmatic ways.

“I think of history as a tool, and I’m always trying to think about how we can put it to use for people,” she says.

UW–Madison is far from alone in scrutinizing problematic parts of its history. The University of Virginia, for example, leads a research consortium of more than 80 higher education institutions with historic ties to slavery. Harvard University, one prominent consortium member, announced in April the creation of a $100 million fund to study and redress its early complicity with slave labor.

Even amid this widespread reckoning, UW–Madison’s effort stands out, says Stephanie Rowe, executive director of the National Council on Public History. While many such projects focus on a particular strand of a university’s past, UW–Madison is employing a broader lens. And while many begin as faculty-initiated research projects, the UW created a public history project and hired a full-time director to see it through. The project is expected to cost $1 million and is being paid for with private funds, not taxpayer money.

“We don’t often see a university initiate and support a public history project of this design and this magnitude,” Rowe says.

Sifting & Reckoning: UW–Madison’s History of Exclusion and Resistance makes space for the university’s underrecognized and unseen histories. Capital Times / UW Archives; Daily Cardinal / UW Archives (2)

Wrongs and Rights

In the Chazen exhibition, the Public History Project unflinchingly faces the university’s past.

Visitors will see the large “Pipe of Peace” used by students a century ago at ceremonies that parodied Native American life. They’ll view posters for campus minstrel shows and watch an undercover film from the 1960s that documents housing discrimination in Madison. The film was thought to have been destroyed by the university but actually sat for decades out of view in UW Archives.

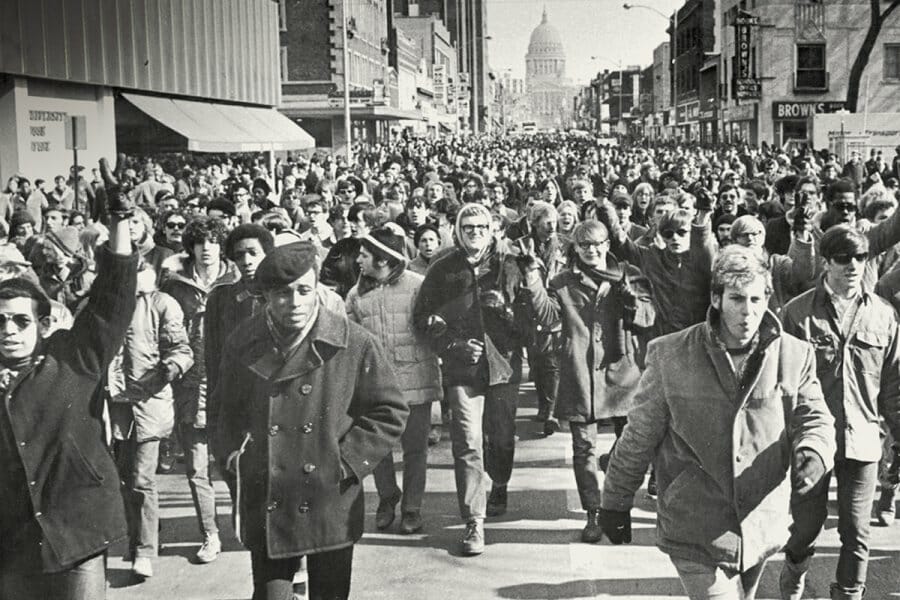

They’ll meet Weathers “Sonny” Sykes ’50, the first Black man to enter an otherwise all-white fraternity at UW–Madison when he joined the Jewish fraternity Phi Sigma Delta in 1949, and Liberty Rashad, one of the organizers of the 1969 Black Student Strike.

They’ll learn about law student Brigid McGuire JDx’96, who in 1994 contested the physical inaccessibility of UW classrooms by removing a portion of a desk with a circular saw to create room for her motorized wheelchair — amid applause from her fellow classmates. And Mildred Gordon, a Jewish woman, who sued the owners of the private Langdon Hall dormitory after arriving in 1929 and being told her room had been given to a non-Jewish person.

Other components of the exhibition explore fraternity and sorority life, Badger athletics, student activism, and prejudice in the classroom. There are deeply shameful incidents, like the campus “gay purges” between 1948 and 1962, but also stories of bravery and resilience as marginalized groups claimed their rightful place on campus.

The exhibition also captures times when UW–Madison as an institution, and especially its students and employees, landed on the right side of history. The Groves Housing Cooperative, founded by the university in 1944, had no racial or religious restrictions and was the first interracial housing cooperative on campus. In another example, many UW–Madison professors and students fought to admit Japanese American students to the university during and immediately after World War II, against stiff government opposition.

“We share in the legacy of what our university has been in the past, whether we realize it or not,” says Joy Block PhDx’23, a doctoral candidate in history who researched Japanese American Badgers for the project. “What I really like about this project is that you get a fuller picture of that history. Sometimes that reveals our failures, sometimes our successes. And sometimes it just reveals our humanity.”

Essential Discussions

Supporters of the Public History Project anticipate criticism, expecting that some will question its value or view it as unnecessary or revisionist history.

John Dichtl, president of the American Association for State and Local History, says it may be helpful for people to view history as a form of detective work.

“To think critically, you need all the information, the full sweep of the past,” he says. “The term revisionist history is often held up as bad, but this is what historians are always doing. Like detectives, they build their cases step by step over time, then revise and update their conclusions based on new evidence, questions, and perspectives.”

It is especially important that institutions of higher education do this work, Dichtl says.

“How can a university call itself a center of learning if it is not fully honest about its own past and its own history?” he asks. “Engaging students in critical thinking about these issues is important for its own teaching mission.”

UW–Madison history professor Stephen Kantrowitz, who chairs the Public History Project Steering Committee, says the project is providing curricular materials to instructors and encouraging them to tour the exhibition with their students.

“My hope is that all of these things the project has identified and collected — the research, the analysis, the interviews, the archives — will enable generations of students and teachers here to use the university’s own history as a laboratory for their study of how people have lived and interacted, how they’ve resolved conflict, and how they’ve worked to change society,” he says.

Kantrowitz likens the project to sitting down with an elder and learning the full sweep of your family’s history, including the worst parts.

“All those painful silences around the dinner table suddenly make more sense,” he says. “That’s what we’re doing here. We’re collectively sitting down with the family photo album and trying to figure out why we have these ongoing conflicts — conflicts over questions that are not unique to the campus but are fundamental American struggles, about race, about gender, about sexuality, about disability, about all sorts of questions that continue to be socially difficult for us.”

LaVar Charleston MS’07, PhD’10, the university’s chief diversity officer, views the project as a beginning, not an end. Its findings will provide a common starting point for essential discussions about how the university addresses or redresses these long-standing issues.

“We have a tendency as a society to act like things didn’t happen, to sweep things under the rug,” says Charleston, who leads the Division of Diversity, Equity, & Educational Achievement. “This is the opposite of that. This is the university taking the initiative and confronting the ghosts that have haunted this campus for decades. Of course, we’re going to unearth some things that may look bad, but I’m proud that we’re being proactive about understanding our history. It’s the only way to make the necessary adjustments so that the impact from discrimination doesn’t continue to happen.”

Finally Being Heard

Charles Holley’s name will be familiar to many alumni. As an undergraduate in the late 1980s, he chaired the UW–Madison Steering Committee on Minority Affairs. The committee’s final document, which became known as the Holley Report, was a forerunner of 1988’s Madison Plan, the university’s first formalized diversity plan.

Holley says the histories of institutions like UW–Madison are often told by those with money, power, and influence. The Public History Project serves as a needed corrective. To those who may criticize the university for “airing its dirty laundry,” Holley has a response.

“It’s already out there. It’s certainly out there in the communities that I care about. If you haven’t heard about it before, you might ask yourself why not.”

By interviewing current students and recent alumni, the project underscores that prejudice remains an issue today on campus. Ariana Thao ’20, who is Hmong, says other students sometimes taunted or mocked her as she walked down State Street. They’d yell “Ni hao” — Chinese for hello — or loudly joke that she probably didn’t speak English.

Thao shared these anecdotes with a researcher and says the experience proved cathartic. “It felt so good to finally be heard,” she says.

Geneva Brown ’88, JD’93, a campus activist in the late 1980s as a member of both the Black Student Union and the Minority Coalition, hopes the Public History Project exhibit will inspire current students to keep working to improve the campus.

“There’s never a past tense to racism and discrimination,” says Brown, a faculty lecturer in criminology at DePaul University. “When students hear, especially nowadays, that we acknowledge the past and understand how it impacts our future, we’re creating an atmosphere where we’re not just giving lip service to diversity, we’re trying to do something about it. I think UW–Madison, with this project, can take the lead on that.”

When Lucchini Butcher gives presentations on campus about the Public History Project, she sometimes reminds people that UW–Madison bills itself as a world-class institution. Ultimately, the project can elevate, not diminish, UW–Madison’s reputation by making sure it lives up to its promise, she says.

“None of this means you have to love UW–Madison any less. You can critique the things you love. You can love something enough to want it to live up to your standards and your expectations.” •

Doug Erickson writes for University Communications.

Published in the Fall 2022 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.