Blow Holes

The shot-hole drill gives the Antarctic a breath of fresh air.

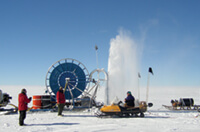

The shot-hole drill (shown during a test near McMurdo Station) carves holes in glaciers in Antarctica. It can drill ice at a rate of six meters per minute, cutting up to twenty holes each day. The drill’s bit is made of steel and tungsten, but the key element is compressed air, used to drive the drill, suspend it over the ice, and clear chips out of the hole.

If you want to drill a few holes in your wall at home, you head to the hardware store to find the right tool. If you want to drill two hundred and twenty-six holes in the Antarctic ice to conduct seismic experiments, however, not even Wal-Mart will offer the right kind of equipment.

You need to seek out a facility like UW-Madison’s Physical Sciences Laboratory (PSL) — it’s the go-to place for scientists and researchers looking for customized tools and instruments, and it’s also where the shot-hole drill was created.

The drill is a first-of-its-kind scientific tool developed by PSL and the Space Sciences Engineering Center (SSEC) in 2001 for UW-Madison’s Ice Coring and Drilling Services (ICDS) to help geophysicists obtain data relating to the dynamics of ice flows in Antarctica.

Researchers asked for this specialized drill because they needed something that was fast, could be easily moved, and could withstand constant use over a very short period of time.

Oh, and it needed to drill through the ice by dry cutting it.

While that sounds logical, in actuality, melting ice with a hot liquid drilling device is standard practice in the polar regions.

A dry drill is necessary because explosive charges are sent down the holes, says Bill Mason, SSEC/ICDS mechanical engineer and one of the shot- hole drill’s primary designers.

Any extraneous water or liquid could alter the reflection of the explosive sound waves traveling through the icy boreholes and skew the findings.

The solution? Air.

As a mechanical cutter head shaves the ice, two air-powered turbines power the drill. “And that air is then exhausted into the holes … blowing the ice cuttings out of it,” says Mason.

“It’s really impressive to see plumes of ice chips rising off the rig as it’s drilling,” says Jay Johnson, drill operations engineer with ICDS.

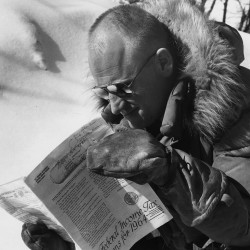

The shot-hole drill was created to specifications provided by principal investigator Charles Bentley, who’s been working in Antarctica for half a century. (See “Cold Digger” in the Fall 2008 issue of On Wisconsin for more on Bentley.)

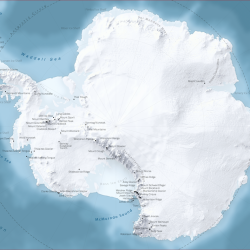

During the shot-hole drill’s first official season in 2002–2003 at McMurdo Station in Antarctica, it drilled two hundred twenty-six holes and a total of 12,686 meters of ice.

“We can drill up to six meters a minute with it,” marvels Johnson. “That’s moving, considering coring drills travel under one meter a minute.”

And it’s still huffing and puffing its way around Antarctica, supporting seismic studies. It drilled one hundred thirty-two holes during the 2009–2010 season at the lower Thwaites Glacier.

“This coming season it’s heading to the South Pole,” says Johnson.

Published in the Fall 2010 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.