The Disinformation Detective

UW professor Young Mie Kim uncovers deceptive political ads on social media.

Between 2014 and 2015, Young Mie Kim applied for a dozen grants to research digital disinformation campaigns during the upcoming presidential election. It was not a sexy pitch at the time.

“I only got one small grant,” recalls Kim, a UW–Madison journalism professor. But she made good use of it, developing an innovative digital tool that tracks ads on social media.

With this new software in hand, Kim landed a second, larger grant from UW–Madison’s Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research and Graduate Education. She used the funding to launch her study of the 2016 election, and her alarming findings made headlines.

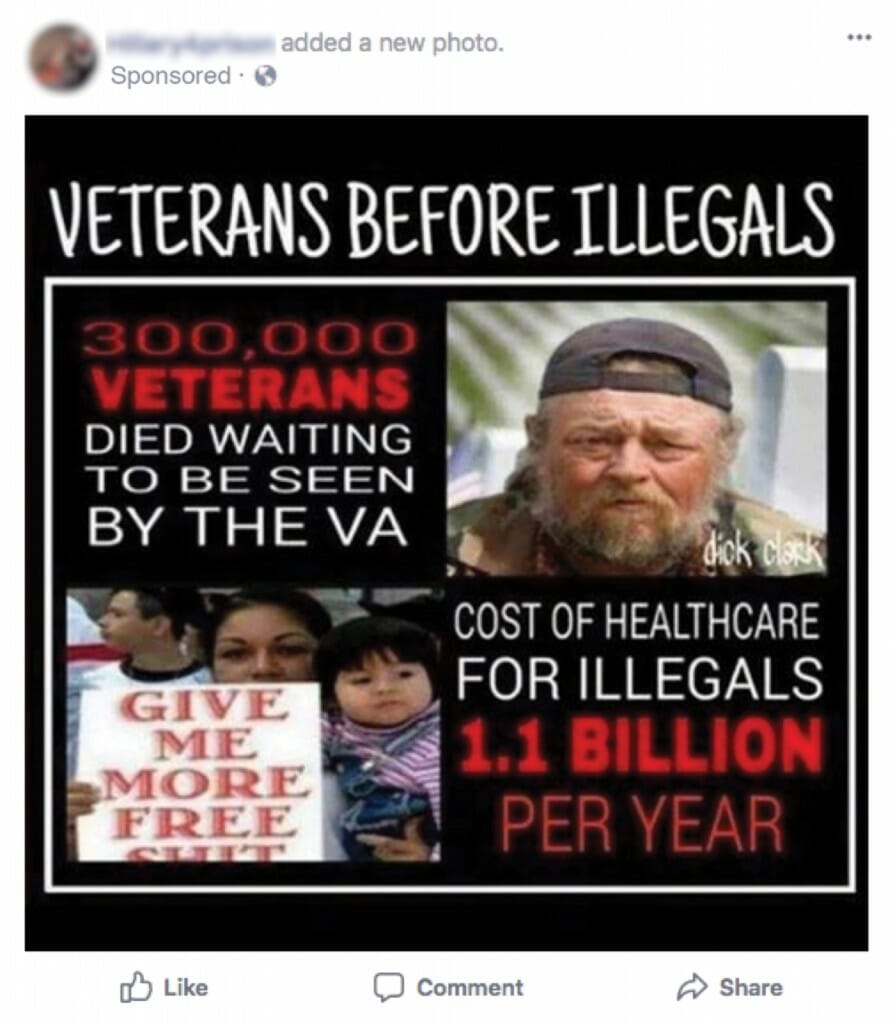

As outlined in her 2018 paper, “The Stealth Media? Groups and Targets behind Divisive Issue Campaigns on Facebook,” Kim and her research team confirmed that the Kremlin-linked Internet Research Agency and other suspicious groups had been spreading disinformation and running divisive issue campaigns on social media to influence the election. And the malfeasance hit close to home: “Divisive issue campaigns clearly targeted battleground states, including Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, where traditional Democratic strongholds supported Donald Trump by a razor-thin margin.”

Since that report, Kim has emerged as a leading expert in digital disinformation campaigns. Her findings were reported by hundreds of national and international media outlets, and her paper received the Kaid-Sanders Award for the best political communication article of the year by the International Communication Association. She was invited to present her research at congressional briefings, and she testified at a Federal Election Commission (FEC) hearing.

For her landmark study, Kim recruited about 9,500 volunteers — a representative sample of the United States voting population — to install her ad-tracking app on their computers. The software would capture ads posted to Facebook and send them to the research team’s servers. Between September 28 and November 8, 2016, the volunteers saw $5 million in paid ads on Facebook.

Her study, says Kim, was the “first large-scale, systematic empirical analysis” that investigated who operated political campaigns on Facebook and who was targeted by these campaigns.

It was a stressful investigation, with Kim hitting dead ends along the way. But she stuck with it, using an impressive set of detective skills to follow a trail of confusing data — until a lucky break helped her expose a threat to the very heart of our democracy.

“Did I Mess Up?”

Kim had for years been studying what she calls “passionate publics,” people who care strongly about an issue based on their identity or values. Think gun rights activists and abortion opponents. She hypothesized that these groups would be the ones running targeted ads on social media during the 2016 election, but she was not seeing many ads from the usual suspects. “There must be something wrong,” she recalls thinking. “This is a half-a-million-dollar project. Did I mess up?”

At the same time, Facebook was full of ads from groups she had never heard of. “I was having a heart attack,” she says. “I’d been studying advocacy groups and grassroots groups, but I didn’t recognize any of these.”

Adding to the stress was the content of the ads, which Kim found very depressing.

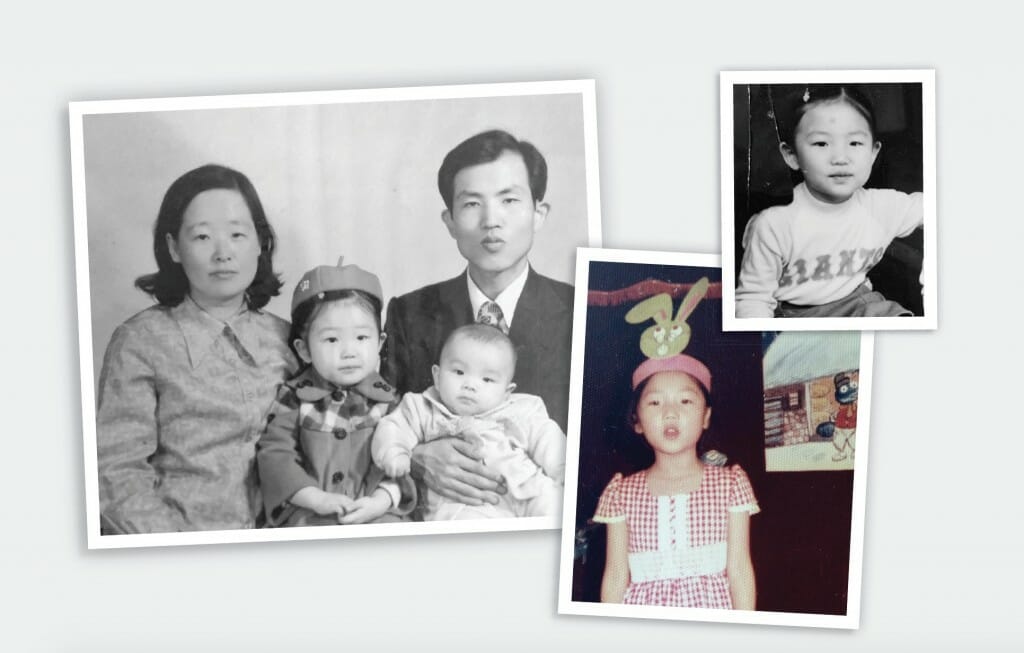

“I’m a first-generation immigrant, and there were a lot of anti-immigrant groups,” says Kim, who was born and raised in Seoul, South Korea.

Once the researchers were able to identify a name associated with a digital ad, they tried to match it with data from the Federal Election Commission, but they found few filings for these political actors. The same was true when they tried to cross-match through the Internal Revenue Service database; more than half of the sponsors of ads they identified were not in either database.

“There was no public footprint, and they existed solely on Facebook,” Kim says. “We didn’t know what to do with these groups. … It was almost like forensic research to find out who these people were.”

But Kim and her team would soon get the break they needed.

In November 2017, the House Intelligence Committee released a group of ads generated by Russian actors along with the account names that they had used on social media. “We matched that information with our data,” she says. “We found that 17 percent of suspicious groups turned out to be Russian actors. They posed as American grassroots groups.”

Kim says it’s scary to consider how these groups are able to disguise themselves and evade detection. “I’m an expert, and I was not sure who they were. … For regular people, the names are generic or very similar to well-known groups.

“People are exposed to thousands of ads and think they are legitimate domestic groups,” she adds. “That is very problematic.”

The fact that some of the ads were Russian-linked sparked a childhood memory, something she had not thought about for a long time. Kim was five or six when she found a flyer on the street that turned out to be propaganda from North Korea, likely dropped from a balloon. The flyer claimed North Koreans were better off than their southern neighbors.

Kim says the groups planting deceptive ads on social media have similar goals to those that dropped propaganda pieces on the streets of Seoul: “They use hatred and social divisions and then target the most vulnerable people and push their buttons.”

Big Questions

After a brief welcome to the 19 UW students attending her Zoom class on April 21, Kim laid down the rules for debate. Three teams would argue for and three against resolutions related to disinformation on the internet. Then there would be a five-minute evaluation period, at which time the debaters themselves would leave the class. The students were instructed to evaluate their classmates on how strong their arguments were, how they used evidence to back up their arguments, and how well they performed.

Anna Elizabeth Aversa x’22 was up first, charged with making the argument that the government, rather than tech companies, should regulate disinformation on the internet.

Drawing on sources included in the course, Dis/misinformation in the Age of Digital Media, Aversa argued that the internet is often used to manipulate audiences and that disinformation is a threat to our democracy.

“Without a doubt, disinformation online is out of control,” she said. Tech companies, she added, “don’t have the resources or the desire to regulate this.”

Next, Rielle Schwartz ’21 performed the cross-examination.

“Although misinformation is a key issue right now, I don’t believe government surveillance would be the best option,” she countered. “How would government regulation change behaviors that are inherent in human behavior? Shouldn’t [the government] be putting more money and effort into media-literacy programs?”

The students also debated whether tech platforms should take down election disinformation or be required to make the methods they use for targeting users publicly accessible.

Aversa appreciates that Kim wants her students to be part of the solution to the evolving issue of digital disinformation. “Professor Kim encourages all her students to think creatively about future steps,” says Aversa. Kim is the type of professor, she adds, who “doesn’t just lecture or put up slides, but rather engages with her students and values the input they bring to class.”

None of the questions debated by the students has an easy answer, but Kim’s research deeply informs her recommendations for reform.

She believes that government officials should play a role in regulating the internet and enact policies relating to disinformation. But, she adds, “Those policies should not be about censorship. They should be about transparency and accountability.”

Kim also believes that ad disclaimers — statements appearing on communications that identify who paid for them and whether they were authorized by a candidate — are key.

While broadcast ads require identification, digital platforms have been exempt from these rules since 2011. But since evidence emerged of foreign interference on these platforms, the Federal Election Commission has been reconsidering the issue. Kim testified before the commission in July 2018 as it was considering rule changes that would require disclaimers on some online political ads.

In comments to the FEC prior to her appearance, Kim argued that a healthy democracy depends on the ability of voters to make informed decisions. Political ads, she said, provide voters “substantive information” on issues and candidates, and campaigns use these ads to persuade voters, raise support, and mobilize voter turnout.

“Disclaimers hence provide voters necessary information about who is behind the political advertising and who is trying to influence their voting decision,” she said.

The FEC still has not taken action on the issue of disclaimers. But there has been some progress on individual platforms. Both Facebook and Google started to require “paid for by” information on ads they accepted in the summer of 2018.

And both platforms now have libraries that collect their ads. Facebook touts theirs as providing “advertising transparency by offering a comprehensive, searchable collection of all ads” running across Facebook apps and services. And for ads that are about issues, elections, or politics, the Facebook ad library also provides information on “who funded the ad, a range of how much they spent, and the reach of the ad across multiple demographics.”

Kim acknowledges that Facebook is better than it was in 2016 in dealing with disinformation, but she is not entirely satisfied with its regulatory policies. One problem is that there is no consistency across tech platforms on the definition of a political ad.

The federal government needs to step up, says Kim, and establish guidelines “so we can see clear definitions across platforms of political advertising, disinformation, and voter suppression.”

The Essence of Democracy

Kim says a love of democracy drives much of her research.

As a child, she heard stories from her parents about the Korean War and lived through political turmoil herself, including pro-democracy protests while she was a student in the 1990s at Seoul National University. Growing up, she thought of the United States as the essence of democracy and transparency.

Kim says she developed a more nuanced view of the U.S. once she moved here for graduate school at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. She received her doctorate in communications in 2004, with a specialization in political communication and new communication technology.

There came a moment in her graduate school career when Kim and her Korean female friends were debating whether they would enter the job market in the States or return to Korea. “We were joking that it was a decision between ‘Are you going to stay and deal with racism or go back to Korea and deal with discrimination as a woman?’ ”

By fall 2004, she was an assistant professor at Ohio State University. Four years later, UW–Madison came calling. The timing was right for her suitors to show off the campus and the lakes.

“It was April,” she says, laughing. “I immediately fell in love with the city.”

Prescription for Change

After her groundbreaking study of the 2016 election, Kim continued researching digital political ads placed in the run-up to the 2020 presidential election. She found that Russian trolls were up to their old tricks and getting “even more brazen in their tactics,” as she wrote in a March 2020 report for the Brennan Center for Justice, where she is an affiliated scholar.

Without safeguards, Kim warns, “Russia and other foreign governments will continue their efforts to manipulate American elections and undermine our democracy.”

Posing as Americans, including as political groups and candidates, these Russian-linked actors tried to sow division by targeting people on both sides of the political divide with posts intended to stir outrage, fear, and hostility. And they had another goal, Kim wrote. “Much of their activity seemed designed to discourage certain people from voting. And they focused on swing states.”

She found the trolls had gotten more sophisticated, closely mimicking logos of official campaigns. And instead of creating their own fake advocacy groups, now they were appropriating the names of actual American groups. The issues raised in the ads, however, remained largely the same: race, patriotism, immigration, gun control, and LGBTQ+ rights.

Kim ends her analysis with a prescription for change. She says tech platforms need to do better at detecting shell groups and fake accounts; federal lobbying legislation needs to be amended to apply to foreign influences working in the digital area; and the FEC must establish a clear and consistent definition of political advertising so that individuals, law enforcement, and researchers understand what is happening in the world of digital political advertising.

Without safeguards like these, she warns, “Russia and other foreign governments will continue their efforts to manipulate American elections and undermine our democracy.”

Charting New Territory

Kim has continued to mine the data she collected from the 2016 and 2020 elections, moving beyond identifying ads and their targets to what impact they had.

In one analysis, she looked at whether ads aimed at keeping people away from the polls in 2016 achieved their intended effect. She matched the ads with the people exposed to them and then looked at whether they voted in the presidential election.

Turnout among all individuals who saw these ads, regardless of demographics, “significantly decreased,” says Kim. More importantly, voter suppression ads clearly targeted nonwhite voters in battleground states. Consequently, turnout among these voters decreased even more.

The report, which has not yet been published, is once again charting new territory. “This is going to be the first study that demonstrates the impact of this targeted voter suppression,” Kim says.

And it could be important for moving the needle. Causation is difficult to pin down in social science, notes Kim, and without a clear link, regulatory changes tend not to happen.

In May, Kim received a notification that someone from Saint Petersburg, Russia, had tried to access her personal Instagram account. She reached out to Instagram’s cybersecurity area, and the issue is under investigation.

It’s not the first suspicious activity to involve her circle. The Twitter account of her research team, Project DATA, was hacked right after publication of “Stealth Media,” though it’s unclear whether it was by a Russian actor. The personal Facebook page of Kim’s former research assistant was hacked at the same time.

Kim does wonder whether her focus on disinformation and foreign interference puts her at any personal risk. She says her parents would like her to change focus.

But she gets much satisfaction out of knowing that she is increasing public awareness of a crucial issue. She has received lots of emails and notes from strangers thanking her for her work.

While Kim spends a lot of time immersed in the world of social media for her research, she has little interest in these tech platforms for personal use.

“I don’t understand why people reveal everything on social media,” she says. “And I know the dangers.”

Kim says colleagues at conferences ask for her Twitter account, which, especially for younger academics, is today’s business card. They don’t know what to say when she tells them she doesn’t have one.

“They are frozen,” she says, laughing. •

Judith Davidoff MA’90 is the editor of the Madison newspaper Isthmus. She is deeply concerned about how disinformation erodes public trust in fact-based journalism.

Published in the Fall 2021 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.