1.1 Million and Growing

Herbarium director Ken Cameron examines samples of plant specimens. Each card includes dried, labeled samples of a particular species of flora. Photo: Bryce Richter.

The Wisconsin State Herbarium traces its roots to the founding of the university.

Among the initial orders from the first UW board of regents in 1848 was for the university to form a “cabinet of natural history.” Founded in 1849 and seeded by the donation of fifteen hundred plant specimens from botanist Increase A. Lapham (some of which still reside in its archives), the Wisconsin State Herbarium now houses more than 1.1 million plant specimens, with approximately one-third of them collected from within the state.

Originally housed in Science Hall, the herbarium moved to Birge Hall in 1910 and then into its current home in 1981 in the hall’s southeast wing. Its vast banks of space-saving cabinets contain carefully collected, dried, pressed, and labeled plant specimens used extensively in taxonomic and ecological research, teaching, and public service.

Sample cards include (top to bottom) Chrysopsis viscida (a golden aster), Cirsium minganense (a variety of thistle), and Ruellia metzae (a wild petunia). Courtesy of Wisconsin State Herbarium.

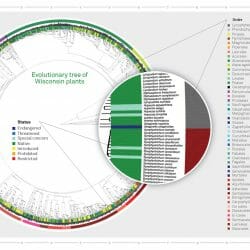

The university’s herbarium is among the ten largest herbaria in the United States and number three among public universities. It also claims the world’s largest collection of Wisconsin plants, made all the more impressive by the state’s cornucopia of plant life unique in botanical research.

“Wisconsin is an incredibly rich, biodiverse place,” says Ken Cameron, who took over as director of the herbarium in 2008. “You have the convergence of three major floristic biomes of the world coinciding in this one place. This is on top of the Great Lakes shores, rich aquatic habitats, and the state’s glacial history.”

The herbarium’s doors are open to the public, and its nearly 400,000 Wisconsin specimens are now digitized and searchable online in the Wisconsin Botanical Information System for researchers, students, and plant enthusiasts anywhere in the world. (Visit www.botany.wisc.edu/wisflora.) Cameron is working to make more of the collection available to a virtual audience — though he feels it can never fully replace the physical collection.

“When we scan these specimens at high resolution, the detail is incredible,” he notes. “You can zoom in and actually see the hairs of the plant. But in my mind, there’s no substitute for the experience of touching, smelling, and feeling the actual plant.”

Published in the Summer 2010 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.