A Muffled Voice

Enslaved for nearly 70 years, George Moses Horton was perhaps the unlikeliest man of letters. After teaching himself to read, he took to poetry, composing and memorizing verses in his mind. For a price, he’d recite them to students at the nearby University of North Carolina (UNC) who were eager to use his love poems as their own. Later, Horton regularly traveled to the university to write poetry and serve as a handyman, using any income to purchase part of his own time from his owner.

Part of Horton’s repertoire, however, was lost in time. Although Horton released three collections of poetry — becoming the first slave and African American to publish a book in the South (The Hope of Liberty, 1829) — there was no record of other types of works until recently, when Jonathan Senchyne, an assistant professor of book history in the UW’s Information School, took a serendipitous trip to the New York Public Library.

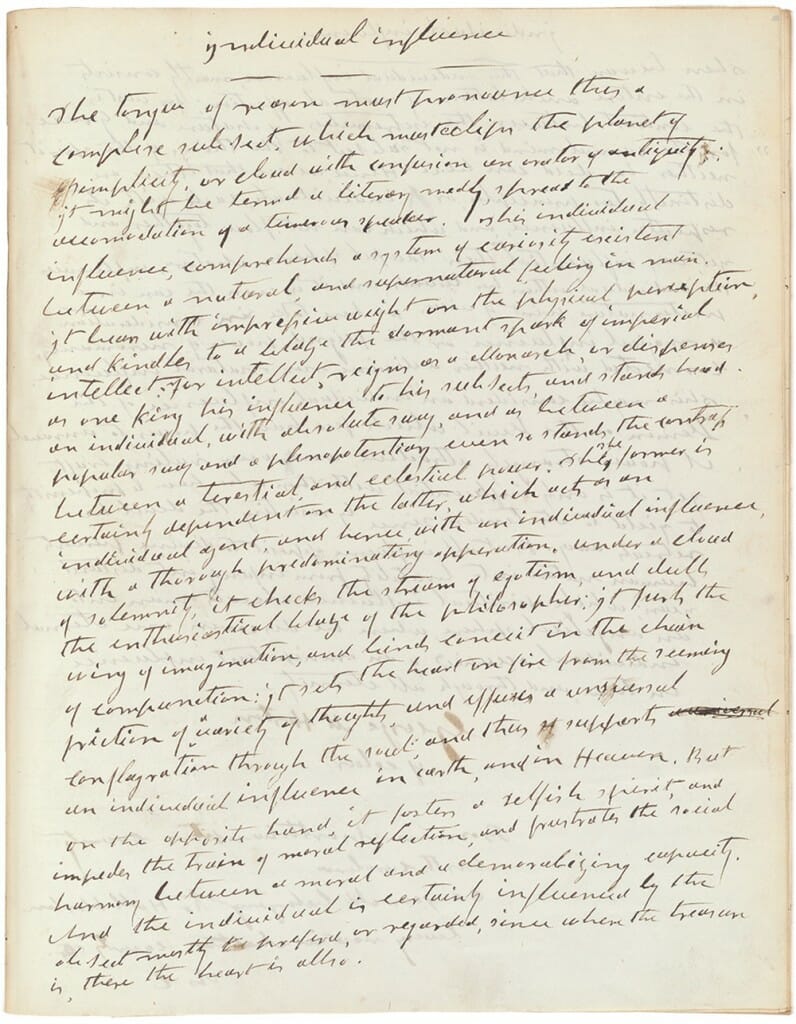

Senchyne was poring through the papers of Henry Harrisse, a French-born lawyer who taught at UNC in the 1850s, when he came across a two-page document with handwriting distinct from the rest. The signature read, “George M Horton, of colour … belonging to Hall Horton.” Senchyne was holding Horton’s first known essay, “Individual Influence.”

“There’s always a certain moment of fascination — the very literal meaning of fascination, which is to have your eyes frozen,” Senchyne says of his find. “It’s a special moment between you and the person who’s writing. You [run] your hand over it, and you have this moment where you’re present to each other across time.”

Senchyne transcribed and published the essay in the October issue of the Modern Language Association’s journal, PMLA. Horton ponders the limitations of “popular” human power compared to “absolute” divine power.

Humans have control over how (and whose) history is preserved and told, Senchyne notes, and those everyday decisions can lead to the century-long burial of an important document and the relative obscurity of an extraordinary poet.

“Why wasn’t [Horton] in all of our history books and literature classes?” he asks. “That’s the question I’d leave people with. Think about your own education and the choices that were made [by people along the way] when history [was] told to you.”

Published in the Spring 2018 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.