Football Fight

In the early 20th century, UW’s Frederick Jackson Turner questioned football’s role in college life.

The first students began gathering by the Red Gym around 9:30 on the night of March 27, 1906. Loud and boisterous, they might have been mistaken for a band of fraternity brothers reveling in a mild spring night after a long Wisconsin winter. A closer look, however, revealed that a number of the young men carried shotguns, while others were packing pistols.

The weaponry was primarily for show and sound effects, but the students figured instilling a little fear in observers couldn’t hurt. After all, the University of Wisconsin was trying to do away with their favorite pastime — the fate of Badger football was at stake. Just that afternoon, the faculty had voted to recommend that university president Charles Van Hise 1879, 1880, MS1882, PhD1892 scrap the team’s fall 1906 schedule and put the sport on hiatus.

A crowd of 100 doubled and doubled again, until eventually about 500 students were there, according to the Daily Cardinal. The chant that rose from the crowd — “Death to the faculty! Death to the faculty!” — did nothing to cool matters.

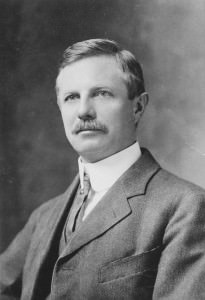

Frederick Jackson Turner 1884, MA1888 — one of the nation’s most esteemed historians and the man leading the effort to get rid of football — watched as the crowd of irate students made their way down Frances Street toward his home on Lake Mendota.

• • •

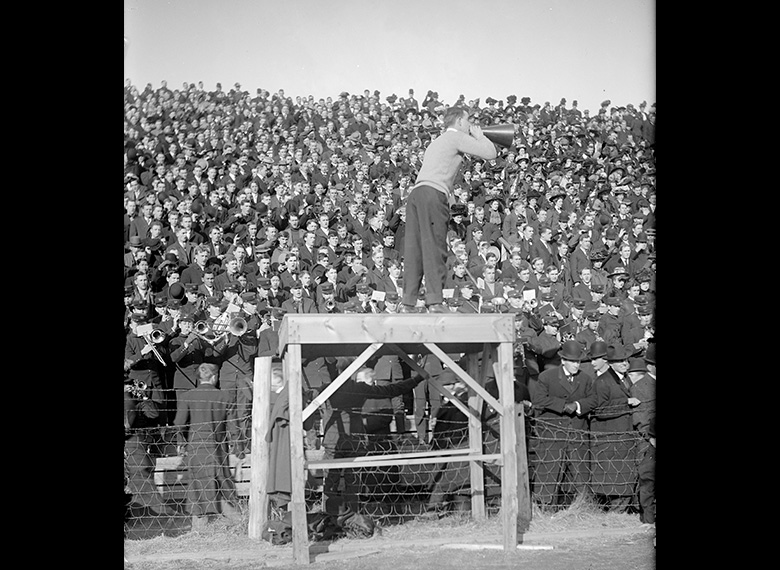

To its critics, college football at the turn of the 20th century was a corrupt and bloody swamp. To its many fans, it was a thrill. Since the sport’s advent in the 1870s, players had become bigger, stronger, and faster. As the number of broken bones, knockouts, and even deaths soared, so did the game’s popularity, attracting thousands of fans from on and off campuses around the country.

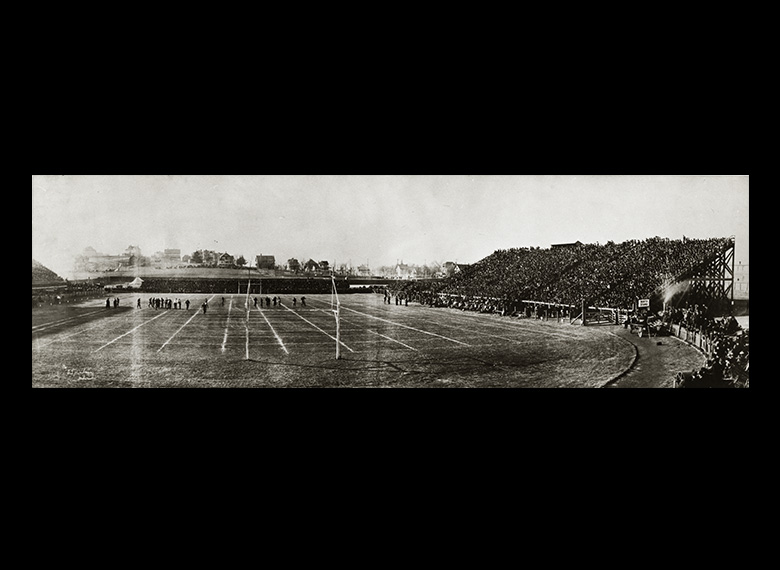

Attendance skyrocketed, as did the money supporters were willing to spend on tickets. University football programs, including the UW’s, brought in enough cash to fund other campus sports. Playing fields with rows of simple wooden bleachers gave way to large stadiums to accommodate tens of thousands of fans. Successful programs were willing to pay huge sums to get the best coaches in the country, in some cases offering salaries that exceeded those of prized professors. Colleges offered training tables for hungry athletes and held preseason camps. Recruiters sought out the most talented high school stars. Semipro players were openly recruited, too. Alumni pledged support to their alma maters by finding good jobs for players — or just paid them cash.

The impetus for change began in the fall of 1905, when a series of muckraking magazine articles detailed the game’s many sins. Collier’s Weekly, The Nation, and the Chicago Tribune all published exposés of college football programs. In October, President Theodore Roosevelt, a Harvard football fan, invited coaches and administrators to the White House to discuss reforms. But it was the death of a Union College football player in a contest in New York in November that finally prompted action.

In December, college representatives gathered in New York to draw up new rules designed to purge violence by “opening up” play. The forward pass (developed by UW alumnus Eddie Cochems 1900) would be allowed in the coming 1906 season, and only six men could be on the line of scrimmage. An offense gaining 10 yards would earn a first down (rather than the 5 yards then in effect). Penalties for holding and illegal forms of tackling would be more severe, and each game would have an umpire, a linesman, and two referees, instead of the two officials who had previously covered the whole field.

While these reforms were thought to adequately diminish the bloodiness of football, demands to remove the corruption that surrounded the college game continued.

• • •

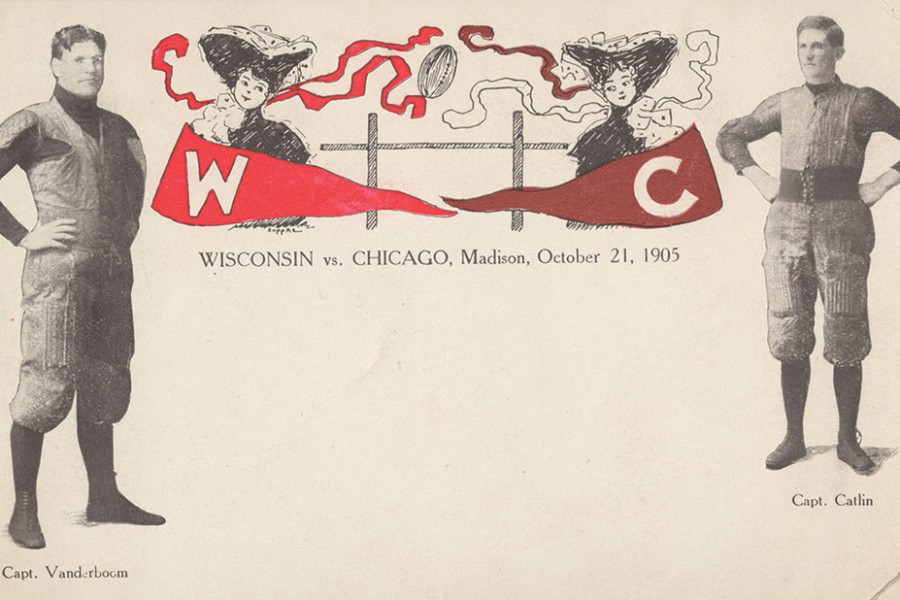

Wisconsin’s vices, along with those of its chief rivals in the Western Conference — Minnesota, Michigan, and Chicago — were outlined in the Collier’s series. The Badger program, it was claimed, brazenly paid a couple of players during the 1905 season. A faculty committee allowed the team captain to take three “snap” courses when it appeared that failing grades were about to make him ineligible. And another player got a $400 contract from the university to move a section of the grandstand at Camp Randall — work that was ultimately done by someone else.

The charges acutely embarrassed university officials in Madison and elsewhere in the Western Conference, prompting the league to call a January meeting in Chicago. Reform was in the air, and Turner led the UW’s delegation.

A native of Portage, Turner, just 44 years old, was widely recognized as one of the preeminent scholars of American history. A dozen years earlier, at the Chicago Exposition, he had presented his famed “Frontier Thesis,” in which he posited that the closing of America’s western frontier would force coming changes in the economic, social, and psychological characteristics of the nation.

In Madison, Turner was also known as an “unwavering enemy of overemphasis on college athletics,” according to his biographer Raymond Billington. In the late 1890s, he helped expel two members of the football team who had been paid to play. He was also known to be a hard grader whose classes were generally avoided by football players.

While a few in the UW’s administration (most notably President Van Hise and Dean Edward Birge) argued for more lenient measures against the sport, the majority of professors wanted wholesale changes, including a two-year suspension. Their argument: competitive sports had gotten completely out of hand and subverted the purposes not only of college athletics, but of college education. Regarding football and campus life, Turner was quoted as saying that the tail was wagging the dog.

In Chicago, Turner and other conference representatives drafted a list of rules intended to fix the game: limit student-athletes to three years of eligibility in any one sport and restrict play to undergraduates only; cut schedules to five games per season; eliminate preseason contests against high schools; cap admission at 50 cents for any game; and require coaches to be college instructors to keep professionals out of the game. Even training tables were to be abolished. The committee urged that if any of the Western Conference’s nine member schools did not agree to abide by the changes, intercollegiate football should be suspended for two years.

In the weeks after Turner’s return, university faculty chewed on the proposed new rules. Among students, while the general sentiment was that some reform was necessary, a complete suspension of football was too hard to swallow. Because football financed other sports on campus, it meant that the track and baseball teams were in jeopardy, too.

Tensions grew as the faculty vote neared. Students staged a protest “carnival” in front of the Wisconsin Historical Society building, featuring football players playing marbles and Ping-Pong to mock faculty concerns over the physicality of their favored game. Where, students asked, was their voice in all this talk of reform? Didn’t the faculty and administration realize that football, in the words of one student petition, “is distinctively the major college sport of today and it is the only unifying force existing at the present time in the University of Wisconsin”?

• • •

Such was the atmosphere on campus when the faculty finally voted to approve the new rules and suspend football at Wisconsin for two years. Some six hours later, 500 students, armed and angry, stood outside Turner’s home offering their say in the matter.

Three faculty effigies, including one of Turner, danced in the air above the crowd gathered at the lakeshore. There were continued shouts of “Death to the faculty!” and new ones of “Put him in the lake!”

Turner stepped out in the light of his front porch, and his appearance seemed to take some of the madness out of the crowd. Something like a reasonable back-and-forth dialogue between professor and students started. Pistols were tucked into belts; shotguns rested on shoulders.

“When can we have our football?” someone yelled.

“When you can have a clean game,” Turner answered. “It’s been so rotten for the last 10 years it’s been impossible to purge it.”

After 15 more minutes of debate, the crowd decided to find a more sympathetic ear. Students marched on to the nearby home of Birge, who played to the audience: “I understand the sentiments of this crowd to be for football,” he shouted as though he didn’t know their answer. They roared back.

To more cheers, the crowd moved on to the capitol and marched around the Square, before heading back toward campus, pulling pieces of wooden sidewalk and fence rails as they moved along. Back down by the Red Gym, they lit a bonfire with their accumulated kindling and set their effigies on fire. The evening ended when the fire department arrived. One of the burning dummies, the Turner effigy, was saved from the flames.

In the end, just one student was arrested: a freshman charged with setting off fireworks on the nearby streetcar line.

By the time Van Hise returned from a business trip to California a few days later, passions had cooled. He announced another faculty meeting for April 5 and promised students that their grievances would be heard. One day earlier, an assembly of some 1,000 Wisconsin undergraduates soberly passed a resolution denouncing the activities of the previous week’s mob — but at the same time lobbied to keep football on campus.

Van Hise offered a compromise: play the 1906 football season with a five-game schedule that would include none of Wisconsin’s major rivals. Games against Michigan, Chicago, or Minnesota brought out the worst excesses in the sport. If those games were eliminated, and the UW instituted other changes proposed at the Chicago conference, the game would be substantially reformed. When Turner agreed, the rest of the faculty acquiesced. The UW’s 1906 football season was saved.

But stopping football’s campus popularity would turn out to be a difficult thing. The Badgers continued to play a five-game schedule in 1907, 1908, and 1909, at Turner’s continued insistence, but rivalry games were back in the mix. By 1910, everyone in the Western Conference had returned to a seven-game schedule.

Turner’s days as a football reformer were over. So, too, was his time at Wisconsin. In 1910, he took a position on the faculty at Harvard.

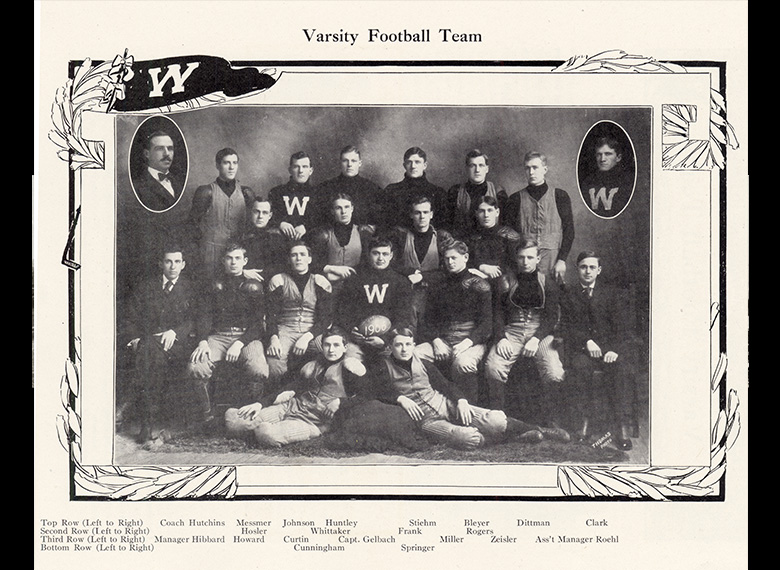

The 1906 Badger football team. UW Archives S08880

An interior view of the old Camp Randall Stadium. UW Archives S09628

Attendance skyrocketed at games since the advent of college football in the 1870s, including at the UW. WHS Image ID 25742

Tim Brady ’79 is a freelance writer based in Saint Paul, Minnesota. His most recent book, His Father’s Son: The Life of General Ted Roosevelt, Jr. was published this year by Penguin/Random House.

Published in the Fall 2017 issue

Comments

Richard Sperry, Law 1971 December 3, 2024

“…college football’s longest-running rivalry….” Mike, sorry, no. Lafayette College and Lehigh University since October 25, 1884.