Irwin Goldman

Irwin Goldman packages seeds for the Open Source Seed Initiative. Using envelopes such as the one below, OSSI sent material to 6,000 people in 16 countries. Photo: Bryce Richter.

Free the seeds, feed the future.

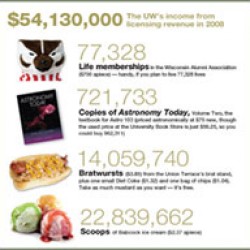

Last April, professors Irwin Goldman of horticulture and Jack Kloppenburg of community and environmental sociology, as well as graduate student Claire Luby, mailed out packages and packages full of seeds. They weren’t launching their own seed business — they were launching a movement. The Open Source Seed Initiative (OSSI) is an effort to create a common human property in plant DNA — in germplasm — one that’s free from the restrictions of patents and licensing and available for farmers and gardeners to experiment with as they please. On Wisconsin sat down with Goldman to talk plants, patents, and the future of food production.

What’s the inspiration for OSSI?

Well, it comes from open-source software. That was the real inspiration for it. Most of our germplasm now gets licensed and sometimes patented. We recognize that that’s a tide that we can’t change, but we thought that if everything goes this direction — if all germplasm gets licensed or generally restricted — there’s a real danger. Several companies control more than half of the world’s seeds.

You have patents on plants, right?

We have three patents — two patents on beets, one on carrots. We have probably fifteen different licenses on carrots and beets. They don’t generate huge amounts of money — they’re beets, right?

But I work for the University of Wisconsin, and all the new varieties that I develop have to go through a channel where I disclose them and then [the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation (WARF)] makes a decision as to whether they want to license or patent. And I have a great relationship with WARF. I love working with them. I am not against what they do. In fact, they’re bringing in revenue that not only supports the university, but supports the kind of stuff I do. It supports our breeding program. And it supports graduate students.

Was WARF okay with OSSI?

They said, ‘Sure, go for it.’ It was fantastic. I felt so good. I felt so positive about working here. Carl Gulbrandsen, [the managing director of WARF], called me, and he wanted to talk about it, and I expected him to say, ‘Well, we can’t do this very often.’ But what he said was, ‘We should be doing this, and not only that, we should try to get funding from [the United States Agency for International Development] and other organizations to support this in the developing world.’ There are plenty of farmers for whom the idea of even buying commercial seed is just completely out of the question.

What’s the OSSI alternative?

The idea here, the phrase we use, is a protected commons. It’s a commons, and anybody can get it. But they have to take the pledge — not to patent these seeds or anything produced from these seeds. Is it legally enforceable? Probably not. But it isn’t about policing. It’s about the moral economy, the social contract with seed.

How many kinds of seeds does OSSI offer?

We released thirty-seven varieties of fourteen different crops. And we put those out in an open-source framework, in these packets, to [First Lady] Michelle Obama and [author] Michael Pollan and the secretary of agriculture, and all sorts of people involved in the food movement and agriculture. We also sent these packets to people who requested them [from] all over the world, over six thousand to sixteen countries.

What are OSSI’s goals?

We really want to foster the tinkering that’s part of open-source software. If you get some code, you create something new with it. That’s the beauty of that. To get some seeds and say, ‘Here’s this population — go and make seed of it and give it to your neighbors.’ Now people send us pictures of their open-source lettuce growing on their patio, and people write to us and say, ‘What do I do now? How do I make seed?’ I love those conversations. It’s really very exciting to think about — people who are, for the first time, thinking about this whole seed-to-seed process. I just love it all.

Interview conducted, condensed, and edited by John Allen

Published in the Winter 2014 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.