Tracking The Ties That Bind

Fred Gardaphé ’76 knew that if he didn’t get out of the Mafia-dominated neighborhood where he grew up, he could wind up dead. UW–Madison provided a way out.

The topic of social class doesn’t come up often in social conversation or in the halls of academia. That’s why journalist and first-generation college graduate Alfred Lubrano decided to address the issue in his book Limbo: Blue-Collar Roots, White-Collar Dreams, which looks at upward mobility through vignettes of individuals who have grown up in working-class families and moved on to white-collar jobs. The author focuses on how many of these “straddlers,” as he calls them, confront social mores of a middle-class world that is dramatically different from the one in which they grew up — and how, even after making the transition, they can’t seem to shake a lingering sense of isolation and of not fitting into either world. The following excerpt tells the story of one such straddler, Fred Gardaphé ’76.

Melrose Park, Illinois, is near enough to O’Hare Airport that a person can read the logos of planes roaring not far overhead. It can get to you after a while, knowing that those people above you are going places, and you’re stuck in this.

The landscape on the main thoroughfares is eye-unfriendly, with barely a tree to offer a break from the character-free, suburban/industrial tangles: a Ford plant, a Sherwin-Williams plant, a Denny’s, a strip mall — it’s as though someone forgot to write a zoning code, allowing fast-food restaurants, factories, and big-box retailers to nest one next to the other in disjointed disarray. Acres of stained, gray parking lots thwart rain from penetrating soil, and rivers of oil-ruined water flow toward Lake Michigan in toxic torrents. Surviving on jet exhaust and industrial stink, Armageddon-ready weeds grow unchallenged and unmowed in the cracks of buckled concrete islands that separate endless flows of truck traffic. Pedestrians are scarce. Nothing is of human scale; it’s a place for machines and buildings, hard and impenetrable. How tough it must be to live here.

Fred Gardaphé did, and it almost killed him. His godfather, his grandfather, and his father were slain here in Melrose, the place some people call “Mafia-town.” They were connected in ways to the Outfit, which is how they refer to the Mob in Chicago. It was a gypsy who saved him: “The third Fred in the family will die,” she foretold, if he didn’t get out. Actually, it was a gypsy, a Dominican priest, and the University of Wisconsin that saved Fred. But that’s getting ahead of the story.

These days, Fred is a Distinguished Professor of Italian American Studies at Queens College at the City University of New York. That shouldn’t have happened. Guys like him finish high school, maybe, then scratch out a working-class life never more than a few miles from the hospitals in which they were born. But Fred had things chasing him: fear is a great rocket fuel. “It was like being in Plato’s cave,” Fred says, “then walking out.”

He returns every summer to see his mom and his friends, buddies who didn’t go to college but remain close. Lately, the reunions have become even more important. Fred’s actually been contemplating moving back to the area. “It’s to be near what is known, and it’s also being known,” he says. “To not have to introduce myself to new people all the time.”

Can a white-collar person do that — return to his blue-collar beginnings and live a new kind of life? For some straddlers, the middle class gets to be a burden, its rituals and requirements forever foreign. There’s an ease to slipping back to old ways. Another reason Fred comes is to find out more about his father’s unsolved murder more than thirty years ago. People must know what happened, Fred believes. But no one ever says. “I need for things to make sense. Because they don’t.” He’s come this time with his daughter, to help her see who he was once.

One thing is for sure: professor or not, he still looks like a neighborhood guy. Stocky and thick, Fred has a goatee and receding gray hair he keeps close-cropped. He wears black shorts and a blue, sleeveless T-shirt to show off arms he used to throw around in boyhood fights. He sort of reminds you of Billy Joel in a distant way. Tonight, he’ll meet his boys for drinks at a sports bar, then maybe go to dinner. They’ll bust his chops about his ride, a 1993 Mercury Sable. They’ve become plumbers and restaurant suppliers, and they all make more money than Fred, without education. Fred’s son once asked him why, with his PhD, he has the crummiest car among friends who never went beyond high school.

Right now, he drives the gas-slurper through Melrose Park, once all Italian, now largely, if not mostly, Mexican. “When I come back, I expect things not to have changed. At least there are the same [jerk] drivers. But you see the changes and have to ask yourself, ‘Who [messed] this up?’ I expect people to still care about the things I’ve stopped caring about.” As we drive, sweet songs like “You Didn’t Have to Be So Nice” pour out of the oldies station Fred programmed onto the car radio after his daughter left to hang out with friends. The audio syrup is the wrong flavor for what Fred’s telling me. “I come from a long line of violent things. My godfather was killed robbing a golf course.” The statement hits you sideways, with its odd juxtaposition of disparate words that rarely work the same sentence. It’s awful and absurd. Do things like that happen? Somebody shot the man as he ran off with duffer money, then his buddies scooped him off the lovely grass, drove him to the hospital, and threw him out on the lawn, where he died before ER doctors could stop the bleeding.

Life was so awful that Fred could easily have become a gangster — so many of the adults in his life were. This was, Fred says, “mythic Mafia land,” with nefarious traditions tracing back to Al Capone, whose turf this once was. “There are people who still consider Melrose Park the place where the Mafia in America comes from.” The Gardaphé family was into laundering stolen money and fencing stolen goods, he said. Their pawnshop was the perfect front. “They were distributors of the stuff that fell off the backs of trucks, essentially.”

Fred passes Dora’s Pizza and has to stop. He used to deliver for Chucky, the owner, and now the two catch up, as Fred eats a sausage sandwich and drinks an RC standing at the counter. Today the news is not good. Turns out everybody Fred used to know is either dead or on dialysis. “Whaddya gonna do?” Chucky asks, and the two men contemplate the question, so very blue collar in its dual implications that everything is out of your control, but you’ve got to learn to live with it. “Whaddya gonna do?” practically qualifies as a working-class philosophy of life.

There’s a break in the conversation, then Chucky looks at Fred and says, “God, Fred, I remember the day Shadow didn’t come in for lunch.” That shuts Fred down, and a pall hangs over the men. Shadow was Fred’s father. They say their good-byes and in the car, Fred tells me that Chucky has his facts wrong. Shadow wasn’t supposed to go to Dora’s for lunch. Fred was supposed to bring his father some food at the pawnshop that Monday afternoon. But he didn’t want to because he knew Shadow would make him work. So Fred sent his younger brother with the lunch; Shadow took the food and sent the boy home.

“I always felt guilty about that. Maybe the killer would have seen me working there and not gone in.” Somebody stabbed Shadow to death. Fred believes it would have been someone his father knew; nobody else could have gotten close enough for a knife assault. And it wasn’t robbery because nothing was taken. “It’s one reason I keep coming back home, to keep replaying it in my mind. It was the most primal scene in my life and the reason I left this place. When I come back, I look at the people and wonder if they remember. It’s not for new leads, really. But to see if his murder has an impact on others’ lives as well.”

After the slaying, people started telling their kids not to hang around with Fred. He became adept at spotting the FBI surveillance cars on the block, and once put a potato in a fed’s tailpipe. Bad times seemed to follow him. When he was fifteen, Fred was on the phone with his grandfather, who was at the pawnshop. By then, Fred was working there more regularly, but he had stayed home that day. Suddenly, he heard gunshots pop over the phone. He and his mother jumped in their car and sped to the shop, only to see his grandfather lying on the floor, bleeding to death. Fred grabbed his grandfather’s gun, saw a guy limping away, and raised it to fire. But before he did, a cop came up from behind and yelled, “Drop it.” The shooter was caught and sentenced to twenty-five years for the murder. It was robbery, pure and simple. But Fred’s grandfather wouldn’t have died if he hadn’t resisted. The only reason he had, Fred claims, is that he was a racist and couldn’t bear the idea of being robbed by a black man.

Mired in hatred and ignorance, steeped in death, Fred was growing up hard. Desperate for Fred to have a man around, his mother asked a neighbor to take an interest. As it happened, he was related to the Genovese crime family in New York. He, in turn, was murdered. Things were not going well for the males in Fred’s life.

One day, Fred’s grandmother saw a fortune-teller, who foretold his demise unless he sold the pawnshop, which had fallen to him. The family believed, and Fred liquidated the place when he was sixteen, selling, he said, to the Jewish Mafia in town. By then, he was attending an expensive Dominican prep school, for which his grandfather had paid. On the streets, he was brawling, getting into fights with black kids, and proving he was a man. In the classroom, he was studying philosophy and Latin, being shown another way to grow up. Fred would do his homework on the sly, sneaking books to the park or rec centers. “Around that time, I started realizing that I was trapped in Melrose. But you didn’t want people to know that you were escaping.” The process was going slowly. Fred got into drugs — speed and acid, mostly. “It was my way of getting out of where I was mentally, because I couldn’t do it physically.”

Still, the Dominicans were having their effect. He was reading Cicero and Plato. In an irony not uncommon in quality Catholic educations, Fred was being taught to question authority — how, in essence, not to be a good Catholic boy who hangs around and does only the family’s bidding without question. “That was the bomb that blew everything up,” he says. “They taught me I had to get out of this place. It was getting hard to remain in the world in which I was born while being nurtured out of it by school. The question became, when do you leave?”

Motivated to go, but without direction, Fred went to a junior college to escape the draft. When the government did finally send a notice, it was a 4-F deferment, in essence a judgment that Fred had failed his physical exam and could not become a soldier. Good news, right? Well, like a lot of things in Fred’s life, there was a mystery to that as well. Fred had never taken an army physical. To this day, Fred believes his family had any potential draft notice quashed through their long-standing connections to organized crime. But no one at home owns up to it. Whaddya gonna do?

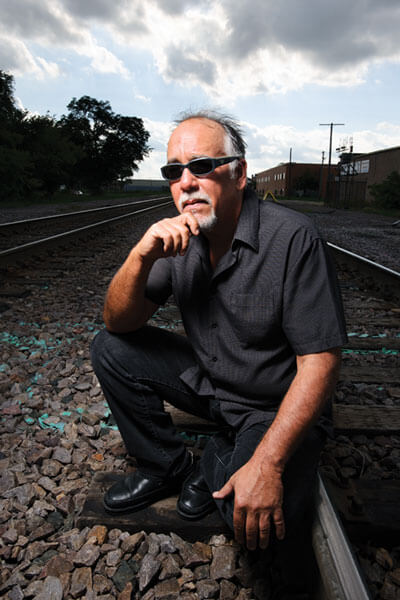

On a recent visit home to Melrose Park, Gardaphé pauses by an honorary street sign that says Fred Gardaphé Way, named after his late father. Photo: Jeff Miller.

One of his college teachers, a white guy, called all the neighborhood guys in the class “racists.” He explained how he’d fallen in love with a black woman. He had his students read Richard Wright and other black authors. He showed his ignorant white charges how they’d been getting it wrong their whole lives. “The bad thing about realizing you’re a racist is that it means everyone who ever taught you anything or told you anything you believed was a racist, too. It’s such an unraveling of all the things that you protected yourself with.”

Enlightened and now totally out of step with the neighborhood, Fred transferred to the University of Wisconsin — “where all the good radicals go.” Language was the big difference. Suddenly, he was in rooms with people whose English was superior to his. Making things tougher, women were befuddling, too. “I went up to girls and said, ‘What are you chicks doing tonight?’ and they’d say, ‘Why do you cocks wanna know?’ My working-class notions about women were they were to be protected. I opened a car door for a girl in Madison and she was insulted. I kind of got dragged into feminism kicking and screaming. You don’t know how deeply working-class you are until you’re in these situations.”

Scholarship lit a fire in his head and Fred straightened out. Now he’s a full professor, but he still worries about the clock at work. Is he keeping enough office hours? he wonders. He has a sense the boss is looking over his shoulder somehow. “But,” he keeps having to remind himself, “I have tenure. I can’t be fired.”

Saturday night and time to meet the fellas. Fred drives to a sports bar in nearby Elmhurst, where he hooks up with the old crowd — Anthony, Patsy, and George. They hug like working-class guys do — a quick embrace, hard backslaps, then release. Gotta do it fast, before anyone thinks you’re gay. Insults soon follow — jabs about weight, baldness, and creeping old age. That done, the boys are ready to settle in for chicken wings and beers. Balding and in great shape, blue-eyed Anthony works construction. Patsy, who’s a little overweight and struggling with the Atkins diet, is national sales manager for a restaurant-equipment company. George the Greek, unique among the group because he still has his hair, is an insurance investigator. All three are fifty years old. Fred is the only one of the four to have graduated from college.

They start with the old stories. Like a vocal group from the 1950s, the guys know all the words.

Back in the day, there were girls, furtive tries at oral sex, and fights. These guys were in a lot of fights.

“The blacks pulled Fred out of the car one night, then they beat the [crap] out of all of us,” Anthony says.

“I had no business being there in that neighborhood,” says Fred, the reformed racist.

“We had state troopers called out,” George says. “There were race riots. I tell my kids it made me a person.”

“We all looked out for each other,” Anthony explains.

“And we’ll do it till we die,” George declares.

George has to go, and the others decide to hit an Italian restaurant in a neighboring town. As O’Hare planes roar overhead, Fred reflects. “Back in those days, we would have died for one another. Once reason I come back each summer is I want my kids to spend time with my friends. They’ll say things about me that give my kids insight into me.” The reminiscing reminds him of the crazy years of violent deaths. “Therapy made me realize how strange my life was back here,” Fred says. “My life after education, from age thirty on, was boring. Good thing, because it’s going to take me the rest of my life to mitigate everything that happened before thirty.”

The men find a spot they promise has good tomato sauce. On the sound system, Frank Sinatra, with his mellow voice, tells the world he did things his way. The waitress brings three Crown Royals for the guys. Fred, the white-collar one, orders veal, and his two working-class friends protest. That’s a switch.

“Fred, they leave ’em in little pens,” Anthony says.

“It’s bad, Fred,” Patsy adds.

“Hey, I like veal.”

The men talk about their wives, past and present. “We didn’t marry Italians,” Fred observes, “because they’re too much like our mothers.”

“Marrying, we all broke the bloodline,” Anthony allows.

I ask Patsy what it was like to hold down the Melrose Park fort while Fred went off to college.

“You know, it’s funny, because Fred never talked about going to college,” Patsy says. “He felt maybe the rest of us didn’t understand his need to go. I really don’t remember any conversation about it. Me, I wanted to go to college, but my father said he needed me in the [restaurant-supply] business. It was depressing. I not only wanted to go to college, I wanted to travel, which I can do now. But it took me thirty years.”

“You were always a good son to your father,” Fred tells Patsy. “If my father had lived, I would have stayed. But there was nothing for me here. Where was I gonna go? But why did I go to Madison? It was totally non-Melrose up there.”

“But it gave you an education of how it was in the world,” Patsy says.

Anthony chimes in that he actually moved to Madison to be with Fred. For eight months, he painted Wisconsin houses by day, then partied with Fred and his new college friends at night. He never had the desire to actually matriculate, although he once made money by showing up at an ACT test and taking it for a less-smart pal. “I got him a scholarship,” Anthony says proudly. “I actually got a better grade for him than I did for myself, when I took the test.”

Maybe it’s the Crown Royals, but the boys turn sentimental.

“Fred, even with your education, you remained Fred,” Patsy says.

“I never felt you thought you were above and beyond us. You always remained yourself.”

“And you got rid of that stupid earring,” Anthony adds.

“I meet Harvard and Yale people who couldn’t hold a candle to you guys,” Fred gushes.

“Really, there’s been no change in you,” Patsy says.

“And you don’t insist we call you ‘doctor,’ ” Anthony adds.

“That’s the thing I’d never call you,” Patsy concludes.

The evening ends that way. In the parking lot, the guys share more hugs and spine-splintering backslaps. Fred is pleased with this trip home. He’s happy that he didn’t learn anything new about his friends. That means he still understands them, still knows who they are.

“You know, I live in two worlds. I have to come back from the one at the university to make sure this one’s still here. I’m so glad to know that it is.”

Reflections of a UW Straddler

Coming to the University of Wisconsin back in 1973 was an escape from a Little Italy that I felt was choking my creativity and pushing me toward mindless conformity with traditions I didn’t understand. I had graduated from a well-respected prep school and completed two years of junior college, yet I wasn’t prepared for a big university in my home state of Illinois. I felt so disconnected to what was happening in the lecture classes that I dropped out.

If it were not for the Vietnam War, I don’t think I would have returned to school so quickly. I had graduated from high school in 1970, eligible for the second year of the national draft. I needed a 2-S [student] deferment and so found my way quickly to a local junior college, one we used to call a high school with ashtrays. Its unofficial motto was “Better than fightin.’ ”

My prep school training made it easy for me to work full- and part-time jobs without interruption in my social life — rock concerts, festivals, and the other recreational activities of my generation. I breezed through the classes, doing little to further my knowledge, save for an English class run by a radical teacher who helped us form an underground newspaper as part of our assigned work. He said that the school for me could be no other than UW–Madison.

My best friend had an uncle who worked at the Department of Public Instruction in Madison, and we went up there for a weekend to check the place out. One look at the Terrace that early spring day was enough for me. People as serious about fun and learning were hard to come by back home. We made the move the following year. I wasn’t sure what I wanted to study, but settled on majoring in English and minoring in communication arts. Each class was an adventure, as was life in the city.

I studied film with David Bordwell and television with Donald LeDuc PhD’70, and my English classes took me deep into literary studies, where I soon found a home in the Mark Twain course of Al Feltskog, the linguistic courses of Charles Read, Jerome Taylor’s pre-Chaucer class, and the writing-for-teachers course of Nancy Gimmestad — where I was first able to establish the validity of my personal story and find my voice as a writer.

The key to all my classes was that I was able to take the streets into the classroom, and apply what I was learning back to those very streets. I did a study of railroad dialect for a linguistics class, and wrote about my neighborhood in my English classes. I learned to integrate the lessons of the ivory-tower Madison campus and blue-collar Melrose Park. That has become the theme of my life and my life’s work over the years.

I took courses in education such as Radical School Reform, and through my volunteer work at radio station WORT, I was able to host alternative music shows and to review books that came out of my classroom studies. Those great experiences prepared me for my early jobs in education, first at traditional and later at alternative high schools in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin; Mason City, Iowa; and Chicago.

My days in Madison seem short in comparison to the life I’ve lived since, but that sense of community — in cooperatives, film societies, campus bars, the Italian neighborhood around Park Street, and in my education classes — gave a working-class kid a sense of belonging. It gave me the chance to work my way into the middle class and to never be afraid to bring my life to my learning, or to use that learning to improve my life and the lives of those around me.

I eventually returned to Chicago for a teaching job and am now a Distinguished Professor of Italian American Studies at Queens College-CUNY. I’ve published eight books on Italian-American culture and have spent a lifetime studying those very traditions that I thought I had escaped when I left for Madison.

Fred Gardaphé

Reprinted from Limbo by Alfred Lubrano. Copyright © 2004 by Alfred Lubrano. Reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Published in the Fall 2011 issue

Comments

A. LaVonne Ruoff September 16, 2011

Excellent story about one of my graduate students at the University of Illinois, Chicago, where he received his Ph.D.

Joyce Hasselman Nigbor October 9, 2011

I love the On Wisconsin Magazine, in general, but no other article has hit home like “Tracking the Ties That Bind,” Fall 2011. I too feel just like Fred Gardaphe – a straddler. In 1955, I came to UW Madison from a small, rural high school in Rock Co. WI where not many women aspired to college; I had a lot of adjusting to do; and I too like to go back for reunions to my former high school in Orfordville, WI to “catch up.” Fortunately, I did not have to deal with violence as Fred did, and my nuclear family was supportive of my sister and my college aspirations. I too “learned how to swim.”

Joyce Hasselman Nigbor

BS 1959

MS 1978

Tanja Pajevic October 19, 2011

This story really inspired me and helped me pull together some of the pieces from my own Serbian-American background. I’d often attributed my struggles to being the daughter of immigrant parents, but hadn’t realized how much our economic background played into the picture. After reading this, I wrote about on my blog:

http://rebootthismarriage.com/2011/09/whaddya-gonna-do-part-1-of-2/

Tanja Pajevic

Reboot This Marriage

Jane Nosal October 31, 2011

This article helped me answer some questions that have lingered for years. I am definitely a straddler that grew up in a near southwest neighborhood in Chicago. I left when I was 18 and put myself through college. Now I understand that vague feeling that I don’t belong anywhere. I also purchased Alfred Lubrano’s book Blue-Collar Roots, White Collar Dreams and cannot put it down. I love the fact that UW has the Working Class Student Union founded by Chynna Haas in 2007. That would have helped me greatly as I struggled through college, graduating in 1983. Thank you so much.

Greg Roselli January 28, 2014

Hi Freddy:

I too grew up in Melrose Park and one of the few to escape. I went to University of Notre Dame. First day of school I was wearing our standard summer outfit, daigo tee shirt, shorts, long black stockings knee high, black shools, and a straw Sinatra type hat. The entire cafeteria, about 2000 guys, went quite. Then I realised they were all looking at me. They had never seen a greaser. I never wore that outfit again. Take care, Freddy.

M S Dee February 10, 2022

I’m from Melrose Park too. Escaped when I was 22 years old. This was a very interesting story. I was friends with Fred’s younger brother back in the day.

The junior college that is referenced is Triton College. During the Vietnam War draft era, the saying was “Triton is better than fightin'”.

Jean Ross March 23, 2022

I moved to Melrose Park when I was 11. The story that Fred writes is uncanny. So much of it seemed so strange even at the time. Getting your haircut in somebody’s basement because everybody was a hairdresser and drinking the dad’s homemade wine. I was 13.

I too did my stent at Triton for 2 years. My parents were old school didn’t believe women needed an education and wouldn’t pay for it ,although they had the money. So I worked part-time and paid for every dime. Triton taught me how bad Vietnam must have been. Lots of guys came back, went to triton, but what I remember the most is their hands shaking all the time and constantly smoking,

anything. I found my way to Dominican university, which was rosary college then, and by age 26, I moved to the north shore, Lake bluff. 30 boring years past. I ve been in Wisconsin four years.

Nobody here is looking for an angle. They actually follow the laws. Like a breath of fresh air.