The World at Their Feet

A new expectation is making the list of must-have abilities for today’s students: global competence. But where do you go to get it, and how do you know when you have it?

Anna Green ’09 placed first in the Urban Landscapes category of the UW’s annual Study Abroad Photo Contest coordinated by International Academic Programs. She shot the photo in 2008 while studying in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Jill Speer doesn’t think she has it, but says she knows people who do. Natalie Eisner x’09, whose mother is French, thinks she possesses some degree of it, while Catherine Skroch x’09, a child of missionaries, is confident that she’s had it most of her life. Claire de Boer x’09 isn’t sure how much of it she has, but she’s certain that studying abroad in French West Africa will give her more of it than, say, spending a year in France.

It is global competence, one of the latest buzzwords in higher education. My interest in the concept was piqued last winter when I traveled to a training ground of sorts – Saint-Louis, Senegal, the site of one of the UW’s more innovative study-abroad programs. There, several UW students were studying at the Université Gaston Berger, living in dormitories with Senegalese roommates, and in the midst of producing a fifty-page paper based on independent fieldwork.

For four months they had been immersed in the French and Wolof languages, and in a largely Muslim culture. (It had been equally long since they had taken a hot shower or washed their clothes in a machine.)

After a week of talking with students halfway through this challenging educational experience, I learned that most were pretty sure that they were acquiring global competence – that essential set of skills, attitudes, and knowledge they will need to succeed in today’s world. But when I queried one of the directors of the program, Jim Delehanty, about the notion, the story got more complicated.

With her photo, “Pottery Market,” shot in Cuenca, Ecuador, in 2006, Kathryn Broker-Bullick ’06 garnered second place in the People and Culture category of the UW’s annual Study Abroad Photo Contest.

Delehanty has been to Senegal “twelve or so” times, he estimates. He spent years in the Peace Corps and later conducted research for his doctorate in Niger. He’s lived in Kenya and Kyrgyzstan. He speaks French and Hausa well, and knows enough Wolof “to make people smile,” he says.

Yet he doesn’t consider himself particularly globally competent.

“It’s a nice concept,” he says during a conversation in his office at UW-Madison, where he serves as associate director of one of the nation’s premier African studies centers. “[But] I’m just not sure it exists in practice.”

Anyone watching the news – and the economy – knows that the world is getting smaller, if not exactly, as author Thomas Friedman puts it, “flatter.” Trade, migration, pandemics, global warming, and a radical shift in wealth from the West to the East – all of these factors and more indicate that we’re living in a world of global challenges that will require global solutions. Our graduates need a mindset to match the world around them. But how exactly do we teach and assess these skills?

Like many universities, UW-Madison committed itself to “internationalizing” its curriculum a couple of decades ago. No longer the exclusive domain of liberal arts departments, international education is increasingly important in professional schools such as engineering, health sciences, and business. Students in the UW’s College of Engineering, for example, can now earn an international certificate by taking sixteen credits of courses that focus on the language, history, or geography of another culture. And programs including Engineers without Borders and the Village Health Project provide students with a chance to participate in community development and public health projects around the world.

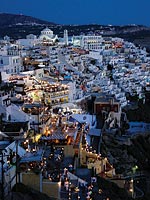

“Fira at Dusk” captured second place in the Urban Landscapes category for John Vanek ’08, who shot the photo in 2007 in Santorini, Greece.

Impressively, more than a third of UW-Madison’s business undergraduates earn some credits abroad, as do more than half of its MBA students. And these students are pursuing the experiences for good reason: the top-ranked Thunderbird School of Global Management, with its patented Global Mindset Inventory used to measure one’s capacity to conduct business on a world stage, says that “individuals with a high stock of Global Mindset … know how to manage global supply-chain relationships … and understand global competitors and customers.”

But as international outlooks and skills become integral to core curricula, universities increasingly face the challenge of evaluating their students’ progress. And this means starting by defining the result: global competence.

A team of UW-Madison faculty, staff, and students recently set out to write that definition. Called the Global Competence Task Force, the group released its findings last fall, delineating not only what the term means, but also how UW students might best acquire it.

Randy Dunham, a management professor who directs the business school’s Center for Business Education and Research, chaired the initiative. On his desk sits a photo frame that rotates digital images of his own travels through the years: animals spotted on safari, a temple in Asia, and a ruin in the Middle East. (Interestingly, several iPods sit stacked on the table between us as we talk. I later learned that these were prizes for an annual, weeklong competition that drew MBA students from as far away as Hong Kong, Bangkok, and Copenhagen.)

Despite his own global leanings, however, Dunham says the task force took a soft-sell approach in its campuswide proposal.

“We are not recommending requirements or standards,” he explains. “We knew that if we said [global competence] is this many languages or this many area- studies courses, it would have been too contentious to be adopted.”

Adam Sitte ’08, who studied in Cairo, Egypt, in 2007, earned second place in the People and Culture category of the UW’s annual Study Abroad Photo Contest for his photo, “Ibn Tulun Mosque.”

In addition, says Gilles Bousquet, dean of UW-Madison’s Division of International Studies, the group knew that there is no one-size-fits-all definition.

“Global competence isn’t going to look the same in engineering, the health sciences, or the humanities – and it’s also going to mean something different to an educator, an executive, or the head of an NGO [nongovernmental organization],” he says.

Instead, the task force listed the components or “competencies” that make up a global mindset, hoping that each campus unit would adopt the definition. Predictably, perhaps, they include the ability to work and communicate effectively in a variety of cultures and languages, and the capacity to grasp the interdependence of nations in a global economy. Somewhat surprisingly, though, many of the core competencies indicate a kind of stance or attitude – the proclivity to engage in solving critical global issues, for example, and a willingness to see the world from a perspective other than one’s own.

What the team doesn’t define, however, is what level of competency is sufficient.

“Developing global competency is a lifelong process,” says Marianne Bird Bear, assistant dean of the Division of International Studies, who sat on the task force. “The university’s role is to make students aware that all disciplines – political science, agriculture, health care – have global, cross-cultural aspects to them. Our job is to provide the training and experiences to develop the global skill set necessary … to address a given problem or understand a certain condition.”

Tyler Knowles ’05 submitted this photo following his study abroad in England. He shot the image of a musician on the island of San Marco in Venice.

Accordingly, the team recommends that campus units require each incoming undergraduate to adopt a “global portfolio” to record the relevant courses and experiences he or she acquires while pursuing a degree. A second part of the portfolio outlines how these activities specifically translate into global abilities that would be attractive to future employers or graduate schools. In developing this portfolio, the team posits, students will plan their educational paths with an eye toward gaining global competencies.

With a goal of clearly defining expectations, Dunham says, “We asked ourselves, ‘What is it going to take to motivate students to see global education as essential?’ We want to create the impression as students come in that it’s normal, that global education is expected.”

While instilling any kind of cross-campus mandate may be slow going, convincing students of the value of international education seems to be a no-brainer. These days, many are well on their way to global-mindedness long before entering college.

Before coming to Senegal, political science and agronomy student Brenda Lazarus x’09 had traveled extensively and studied abroad in high school. She values her friendships with international students on campus for the exposure they give her to perspectives from, say, Mexico or the Philippines. A Minnesota native, Lazarus says that international exposure helps her develop a good knowledge of diverse issues and cultures so that “if [I] go abroad for [my] work or deal with someone from a different culture,

everything will go well.”

What’s more, she says, learning about other cultures has given her the self-possession she’ll need for the work she hopes to pursue in an overseas governmental agency or NGO after graduation.

A girl signs “I love you” in this photo, shot in Ngileni, South Africa, in 2007. Libbie Allen ’08, who studied in Cape Town, South Africa, earned first place in the People and Culture category of the UW’s annual Study Abroad Photo Contest.

Anyone who has moved to another country can recount that moment when the romance of living in a new culture was tempered by everyday concerns – a visit to the doctor, for example, or the need to decipher a cell-phone plan. These are the moments when we see other parts of the world as equally complex and mundane as our own, and not just as the colorful backdrop for our adventures.

What is more, the challenge of independently producing, say, a fifty-page thesis or meeting the academic standards of a world-renowned university in another language means that students must take seriously the “study” in “study abroad.”

“I’m more independent now,” Lazarus tells Delehanty and me at the Senegal university’s buvette, an outdoor snack bar, over instant coffee in cups stamped “Made in China.” “I’m more confident that, whatever situation I’m in, I can deal with it.”

(Of course, the UW’s International Academic Programs office concerns itself, first and foremost, with students’ safety, briefing them before departure, establishing onsite points of contact, and maintaining a 24/7 hotline.)

To Dunham, developing confidence is essential. “International exposure challenges the way people see, the way they think, the things they see,” he says. “It makes them much more competitive professionally.”

Such exposure also prepares students for jobs that are “outside of their comfort zones,” he adds. “If you’ve done a study abroad in India, is it going to be intimidating for you to live in New York City? I don’t think so.”

Even those who choose to live and work in Wisconsin will be ill prepared without a global mindset, says Mary Regel ’78, director of the Bureau of International Development in Wisconsin’s Department of Commerce, who served on the UW’s global task force.

“Companies are looking for employees who have a broad view of the world,” she says. “They want their workforce to be cognizant and respectful of other cultures. Wisconsin is becoming more diversified, and it’s a rare company these days that doesn’t have some interaction with other cultures.”

Laura Burns ’09, who studied in Seville, Spain, in 2008, earned third place in the Natural Landscapes category for this photo, which she shot in Hallstatt, Austria.

Dunham puts it bluntly: “If you only think domestically, you’re more limited in your own choices and, ultimately, you limit the vision of the firm or company you work for.”

For some students, success in the job market – while a welcome byproduct – isn’t the only reason to enhance their global competence.

“Globalization has offered enormous opportunities to the human race,” says Bousquet, who founded UW-Madison’s pioneering Professional French Master’s Program. “But it’s also opened many challenges, most pressing among these the need to keep the human condition – to ensure secure and just lives for everyone – at the center of our focus.”

Happily, studies reveal that global competence seems to go hand-in-hand with the kinds of qualities, such as open-mindedness and compassion, we’ll need to prevent and repair the inequalities that our shrinking planet presents. Recently, a senior scientist at the Gallup Organization released findings from a Global Perspectives Inventory suggesting that those who see themselves as global citizens most often also feel a need to “give back to society” and “work for the rights of others,” and demonstrate a willingness to grapple with complex issues that may present more than one solution.

The director of Harvard’s International Education Policy Program recently argued in the Chronicle of Higher Education that globally minded people would more likely respond to world events with empathy, interest, and understanding. Second only to these qualities are those that speak more to skills than attitude: the ability to communicate in different languages, for example, and a broad and deep knowledge of world histories and cultures.

Global competence, you might say, is a combination of cross-cultural knowledge and the kind of personal and intellectual inner journey that an international experience offers.

To Delehanty, who has overseen the progress of study-abroad students for a decade, and who knows better than most how the world opens eyes, it’s the notion of mastery that is troublesome.

Emily Palese x’10, who studied in Oaxaca, Mexico, in 2008, earned second place in the Natural Landscapes category of the UW’s annual Study Abroad Photo Contest for her photo, “Hierve del Agua.”

“I guess the idea of ‘competence’ makes me uneasy – the thought that there’s a skill set that we all need to master,” Delehanty told me on our last day in Senegal. “Isn’t it really the opposite? Isn’t humility the common denominator of people who function effectively away from home? There are uncountable opportunities in our lives to learn humility. I’m not convinced there is an internationalist

version of it.”

Still, he concedes, going abroad will surely shake up your certainties if nothing has done so before. And that uncertainty leads to a new kind of insight.

As one UW student in the Senegal program, influenced by her everyday French, concluded, “It’s like there is savoir and then there is connaissance. You can know a lot about the world, but global competence is about understanding it.”

Published in the Summer 2009 issue

Comments

Molly Cohen September 27, 2013

I really loved this article. Very interesting and thought provoking! Just makes me want to go to University of Wisconsin even more, and can not wait to study International Studies.