A Gentleman and a Scholar

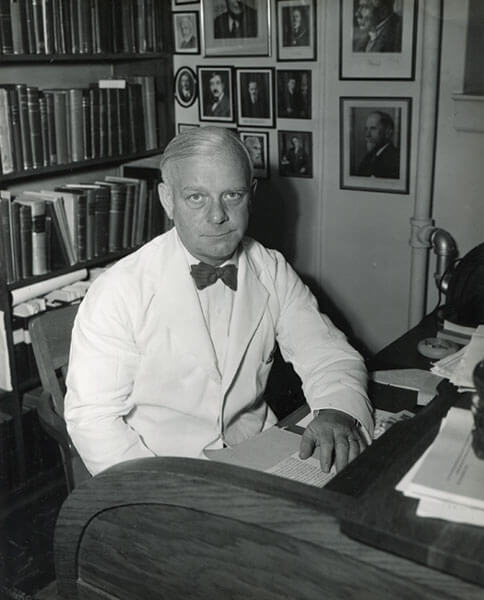

Hans Reese, here with some of the books he loved to collect, first came to the UW in 1924 when recruited to treat Wisconsin patients with neurosyphilis. Courtesy UW–Madison Archives.

He used novel techniques to eradicate syphilis in Wisconsin. He identified PTSD long before it had that name. Professor Hans Reese was a man ahead of his time.

It was 1944, and UW neurologist Hans Reese received a curious invitation that he decided he couldn’t refuse.

Samuel Goudsmit, a professor of physics at the University of Michigan, asked Reese to consider joining a top-secret Pentagon mission. A German immigrant eager to serve the adopted country he’d grown to love, Reese readily agreed.

He wasn’t an intelligence officer or even a physicist. But by that time in his life, he had been an Olympian, gained attention for his research on a wide variety of neurological and psychiatric disorders, and become Wisconsin’s first modern neurologist.

Omnivorous in his interests and relentlessly inquisitive, Reese fell in love with Native American culture, collected a massive library of books that he eventually donated to the university, and, with his wife, cultivated one of the city’s best gardens. He devoted his life to helping others, particularly the medical students he mentored at the university.

He possessed a “knowledge and an interest [in the world] that has about gone out of medicine today,” said Paul F. Clark, who was chair of the UW’s medical bacteriology department at the time.

It seemed that everyone knew Reese — and he them.

And that’s perhaps how this man, who had a constant desire to contribute in some way, became an American scientific spy during World War II. Far ahead of his time, Reese forged international ties in science and medicine that reached beyond the boundaries of the UW, bringing recognition not only to himself, but also to his institution.

Born in Bordesholm, Germany, in 1891, Reese did not want to be a doctor like his famous uncle, Gustav Adolf Neuber, a pioneer in sterile surgery. Instead, he yearned to be a soccer star. He ran fast, loved the game, and played whenever he could. He was selected for the German national soccer team that competed at the 1912 Olympics in Stockholm. When he returned home, his family pushed him to find a career.

The meticulous journals Reese kept while attending medical school in Germany demonstrate his passion to learn whatever he could and contribute to advances in his field. Courtesy of UW Department of Neurology.

Reese juggled military service during World War I with his education, earning his medical degree in 1917 from the University of Kiel. He served as an assistant physician in the German navy, and then went on to study pathology and internal medicine. He developed an interest in neurology and, in particular, neurosyphilis, a form of syphilis where the syphilis-causing bacterium T. pallidum infects the brain and spinal cord, causing dementia and paralysis.

When Reese first came to the United States in 1920 — to provide medical care for an important German-American family — he seized on the trip as an opportunity to study American medicine. He met neuropsychiatrists and toured hospitals and universities to learn all that he could.

While attending a course on neurosyphilis at New York City’s Bellevue Hospital, he met William Lorenz, then chair of the UW’s neuropsychiatry department and head of the state’s Wisconsin Psychiatric Institute. At the time, about 13 percent of patients in Wisconsin’s mental hospitals suffered from neurosyphilis, and the institute was actively studying potential treatments. Learning of Reese’s shared interest, Lorenz invited him to Madison to help test for and eliminate the dreaded disease.

Until the advent of penicillin in 1943, syphilis was one of the most feared of all diseases. In the early twentieth century, German scientists vigorously researched new treatments. One of the most promising involved giving patients malaria. Scientists believed that they might kill the bacteria that caused syphilis with the high fever that accompanied a malarial infection, and then cure the malaria with quinine. Treating one deadly disease with another — strange as it may seem — was the basis of a Nobel Prize in 1927, and Reese was involved in the initial phases of this cutting-edge research.

When Reese first stepped off the train at the Mendota psychiatric hospital stop in Madison in 1924, he looked around and wondered what he had gotten himself into.

“I was surrounded by cornfields. I didn’t see any city, any houses,” Reese recalled. He remembered the warning his mentor and famed New York City neurologist Bernard Sachs had given when Reese mentioned his potential job in Madison. “Young man, for a year, take this job, but any time over … is just a waste of time. There is no culture in this city,” Sachs wrote.

Walking to the car sent to meet him, Reese asked the driver, “What is this? Where is the city?”

“City? That is a state institution there,” the driver replied, gesturing toward the Wisconsin Psychiatric Institute. Reese had not taken Sachs seriously until that moment. He turned and surveyed the institute’s lonely location — far from the city — on the grounds of what today is Mendota Mental Health Institute.

Despite his initial impressions, Reese soon grew to love his work and his new home on the bluffs above Lake Mendota. He enjoyed walking from the institute along what was then mostly open lakeshore to downtown Madison to see movies at the Strand Theater.

A year after Reese arrived, the UW began a four-year curriculum for its medical school, and the psychiatric institute was transferred to campus. He was offered a job in the new neuropsychiatry department, and, with his “heart throbbing with joy and happiness,” he accepted.

Reese introduced the malaria treatment to neurosyphilis patients, undertaking the first study of its kind in Wisconsin and one of the first in the United States. In time, he reported improvement in all sixty-four of his initial patients, including 10 percent he discharged from the hospital. He then reported even better results with a combination treatment of malaria and an arsenic-based drug first shown to be effective by Lorenz and his UW colleague A.S. Loevenhart.

By 1940, the U.S. Public Health Survey found that Wisconsin had the second-lowest rate of syphilis in the country.

Reese had quickly made himself at home in his new country. He married and was named a professor in 1929. He joined multiple medical societies, served on several committees of the American Medical Association, and by 1939, had become director of the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology. A year later, he assumed the chair of the UW neuropsychiatry department.

By 1942, his expertise in both psychiatric and neurological disorders made him a natural choice for a new endeavor. He became a consultant for an American agency created to coordinate scientific research for military purposes. Military medicine was of the utmost importance to the U.S. government, which needed to keep troops mentally and physically healthy.

Less than two years later, Samuel Goudsmit asked Reese to join a top-secret mission — an arm of the Manhattan Project known as the Alsos Missions — that was charged with capturing scientists and materials related to Nazi Germany’s program to develop atomic weapons. Concerns about Germany’s nuclear capabilities had haunted the Allies since 1939, but little had been done to investigate, for fear of revealing U.S. plans.

As the Allies made inroads into Europe, General Leslie Groves initiated a novel experiment: bringing civilian scientists into a vital intelligence mission. The combination of skills was important, given that the intelligence officers did not know enough about science to recognize important findings, and the scientists were not trained spies.

Reese had much to recommend him. He was familiar with German universities, likely places where nuclear weapons research would be conducted. As a native German speaker and a scientist, he could quickly determine whether documents found in labs and information obtained from captured scientists pertained to the investigation.

As the mission progressed, its scope expanded beyond nuclear weapons intelligence to include nearly all German science — including radio and missile technology, and biological and chemical warfare — so that the Allies could determine what the Germans considered vital to winning the war. Field units were deployed to investigate universities, medical laboratories, and even concentration camps.

Reese traveled to the mission’s London office in July 1944, following weeks spent near Washington, where he trained in weapons in the morning and intelligence tactics in the afternoon. He’d received reluctant permission from the UW to take a leave of absence, though he’d lied about the specifics due to the mission’s secrecy.

After several weeks in London, Reese landed in France, traveling closely behind the lines of Allied armies advancing toward Paris. He intended to go to Cherbourg, but intense fighting in the area led him to Le Mans in northwest France. There his unit found containers of peroxide stashed in a cave. They quickly determined that peroxide was the propellant fuel for German bombs that had inflicted heavy casualties on the British. Amid growing fear that the bombs might be fitted with a toxin that causes botulism, destroying fuel sources became an Allied priority.

Reese helped to study the bombs, finding the experience illuminating, despite his lack of experience. “I didn’t have any idea [what to do], but you can always learn,” he explained.

His unit also provided critical information on the psychological effects of bombing. He talked to Allied soldiers about what weapons they feared most and why, and he offered suggestions to military officials about how to help soldiers suffering from the mental effects of warfare — what today is called post-traumatic stress disorder.

Reese was particularly interested in phosphorous bombs, which could cause deadly chemical burns. He worked with the Army Air Corps to develop leaflets that were dropped on German-occupied territories to warn about the bombs. Once dropped, the bombs gave off billowing clouds of white smoke that often made the enemy surrender out of fear before there were any casualties. Reese evaluated the effectiveness of these tactics in France, remaining close to the action throughout the summer of 1944.

Returning in October 1944, Reese reported his observations to a military committee at the Pentagon, highlighting, in particular, the importance of morale in winning wars. Demoralization of German troops, he concluded, likely contributed nearly as much to their defeat as Allied firepower. His report earned the praise of the War Department’s assistant chief of staff, who wrote, “[The department] should be everlastingly indebted to the University of Wisconsin for its generosity in being willing to forgo temporarily the benefits of your very specialized background in order to prosecute the war.”

Reese continued his work with the War Department in 1945, evaluating how the conflict had affected German civilian medical care and education, and how the country had managed to avoid major disease epidemics. He traveled to German universities, meeting with physicians and researchers to explore how dramatically the war had altered the country’s medical system. With few intact educational institutions and a critical shortage of trained men to fill medical positions, Reese advised, keeping the nation healthy presented a serious obstacle to Germany’s recovery.

Finally back at the UW in late 1945, Reese’s collaborative interests continued to guide him. He invited students and physicians from abroad to work with him, seeing these exchanges as an “effort toward international goodwill.” Students came from Germany, Turkey, Iran, Korea, and Greece.

Some years later, in 1954, Reese spoke out forcefully against Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy at a meeting of the American Neurological Association. Expected only to stand up and give a bow, Reese instead seized the podium and decried McCarthyism as a form of the Nazi hysteria that he feared would destroy his new country — as it had his birthplace. The speech made a lasting impression on his colleagues, who recognized how brave it was for this man with a thick German accent to denounce the powerful senator. Reese’s UW colleague Francis Forster called it one of the most courageous acts he’d seen in medicine.

In 1956, the UW neuropsychiatry department was split into two departments — psychiatry and neurology — with Reese named to chair the latter. But his travels abroad weren’t over. In 1959, he spent six months in Japan, teaching and helping to establish a neurology department at Kyushu University. In 1966, he made international headlines when the university conferred an honorary degree upon him, the first Japanese degree ever awarded to a foreigner.

He also spent six months in Egypt as a Fulbright professor, and returned to Germany to study the progress in neurological research and medical education since the war. In 1962, the Federal Republic of Germany awarded him its highest honor for his achievements in medicine and for increasing German-American cultural understanding.

Reese officially retired from the UW in 1962, although he continued researching and writing until his death in 1973. He wrote articles and lectured on a wide range of topics, from the history of German labor unions and medicine in ancient Egypt, to Native American scalping practices and medical care on the American frontier. He’d won commendations for his service in two world wars, one from Germany and a second from the United States, and he’d earned the respect of his peers around the world.

“Dr. Reese brought modern neurology to the state of Wisconsin,” says UW neurologist Andy Waclawik. “Perhaps his most important legacy is the generations of excellent neurologists, taught and mentored by him, who have served Wisconsin and the UW, and given us a national and international reputation.”

On the eve of Reese’s retirement, former student John Toussaint ’49, MD’51 honored his mentor in a letter, writing, “I learned [from Reese] the merits of being meticulously thorough, of being scrupulously honest, and of being, above all else, a gentleman beyond reproach.”

Erika Janik MA’04, MA’06 is a Madison writer and radio producer.

Published in the Fall 2012 issue

Comments

Benjamin Rix Brooks MD January 1, 2013

Excellent description of an icon of the Neurology Department at the University of Wisconsin. Consider doing a similar story concerning Henrik Hartmann who was an icon of the Neuropathology Division in the Department of Pathology.

steve kornguth April 5, 2013

It was a pleasure to read the remembrance of Hans Reese, a mentor to all new faculty of the Neurology Department in the early 1960s and a scholar/gentleman in his interactions with the community, University and nation. Hans appeared often in departmental activities and devoted much precious time to encouraging young investigators. He was an early example of mentoring in the department and medical school.

These recollections are very warming and meaningful

Best

Steve

The Poet January 8, 2026

Was Hans a part of project paper clip? His neurological background would be ideal for mind control.