With New Eyes

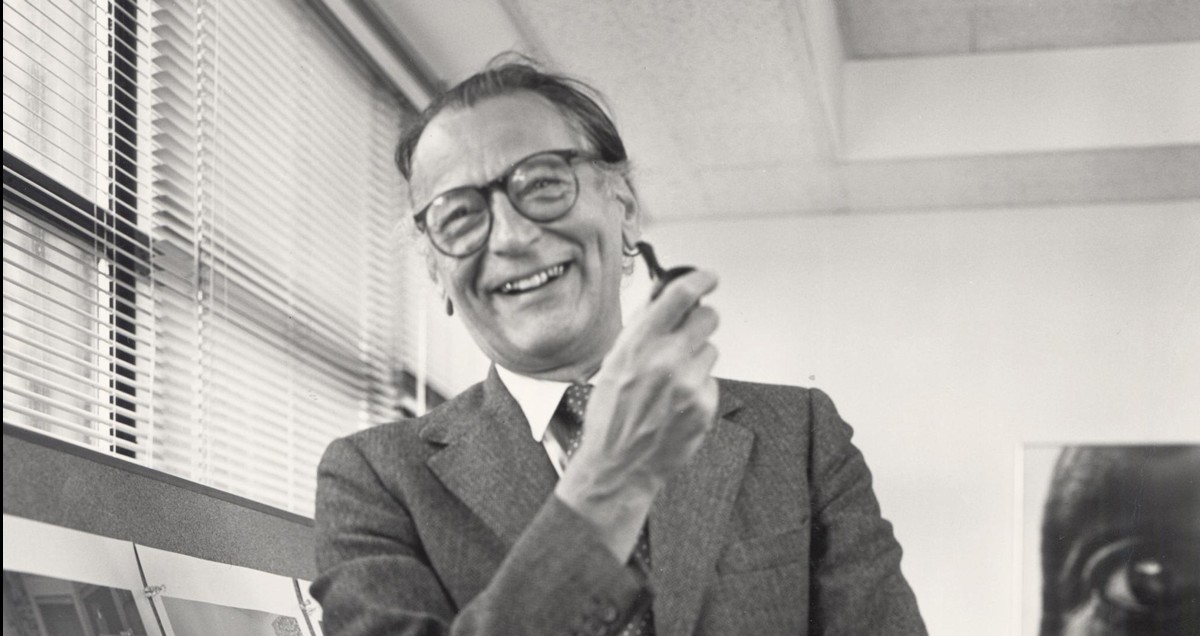

As a curator and practitioner, John Szarkowski '48 helped shape our view of photography — and the world.

“Last week I finally got home … where I could think about the future and look at Lake Superior at the same time. No matter how hard I looked, the lake gave no indication of concern at the possibility of my departing from its shores, and finally I decided that if it can get along without me, I can get along without it.”

The quote above is from a letter John Szarkowski ’48 wrote in 1961 to Edward Steichen, accepting an invitation to lead the Museum of Modern Art’s department of photography. At the time, Szarkowski was already an accomplished photographer himself. He had shown his work in well-reviewed exhibitions and finished two books of his photography. He was beginning a new project, funded with a grant from the Guggenheim Foundation, to photograph the Quetico Superior wilderness area along the Minnesota–Canada border.

The Ashland, Wisconsin, native was living in a house overlooking Lake Superior in Bayfield County. It is understandable that he would need a moment to gaze at the water and gather his thoughts before committing to move to New York City. But even if he felt divided — and a little miffed that his beloved lake did not rise up to protest the prospect of his leaving its shores — he went on to a 29-year tenure at the Museum of Modern Art, becoming a singularly influential curator who, as a New York Times critic once put it, “almost single-handedly elevated photography’s status … to that of a fine art.” He helped people look at photography, and the world, with new eyes.

With an artist’s natural curiosity, Szarkowski championed dozens of innovative young photographers, including Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander, Garry Winogrand, and William Eggleston. Drawing on his own decades-long study, he also wrote about the work of 19th- and 20th-century photographers in clear, evocative prose that doubled the pleasure of looking at pictures. With Szarkowski as your learned and witty guide, you feel as if you have entered into the spellbinding scenes that great photographers catch with their cameras.

Garry Winogrand

Diane Arbus, Love-in, Central Park, New York City, 1969

© The estate of Garry Winogrand, Courtesy of Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco, And Luhring Augustine, NY

For his first major exhibition at the museum, The Photographer and the American Landscape in 1963, Szarkowski selected sweeping, voluptuous portraits of the American West and Midwest. Some were by Ansel Adams, Alfred Stieglitz, and other well-known 20th-century artists, but others were taken by relatively unknown photographers who set out to document the Great Plains and Rockies in the decades after the Civil War. “This work was the beginning of a continuing, inventive, indigenous tradition, a tradition motivated by the desire to explore and understand the natural site,” Szarkowski wrote in the introduction to the exhibition’s catalog.

In the same essay, he described Henry H. Bennett’s photos of Victorian men and women canoeing in the Wisconsin Dells in the 1880s. He called the subjects “neatly dressed, poised, superior to the site, but with friendly feelings toward it” — people discovering their own “identity with the wild world.” His smooth, nuanced prose gives readers the sense that they are themselves gliding with excitement and wonder through the magical hushed Dells, long before motorboats ever buzzed those waterways.

Henry Hamilton Bennett

Canoeists in a Boat Cave, Wisconsin Dells, ca. 1890-95

© The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by Scala/Art Resource, NY

Szarkowski acquired his first camera at age 11, and photography became one of his chief hobbies alongside playing the clarinet and trout fishing. On the same day he arrived at the University of Wisconsin in 1943, he visited a local portrait photographer named Frederica Cutcheon, whose work he had admired in the window of her downtown studio on an earlier high school trip to Madison. He introduced himself as a photographer looking for work, and Cutcheon hired him on the spot for 75 cents an hour.

It was a handsome wage for a student in those days, helping Szarkowski pay for his lunch at Rennebohm Drug Store, where he hung out with buddies from the Pro Arte Quartet. Most important, working as Cutcheon’s assistant (with open access to her darkroom) gave him the chance to watch an accomplished commercial photographer who understood lighting and composition and, he said, “knew something about how a picture was put together.”

Szarkowski majored in art history because he thought looking at other people’s well-made photographs would be a good way to learn about making his own. But then, he said, he got “interested in not only the fact that they were well made, but that they were about interesting ideas, and that they were part of interesting traditions.”

John Fabian Kienitz ’32, MS’33, PhD’38, one of Szarkowski’s art history professors, gave him a particularly important piece of instruction: go to the Union and buy a copy of Walker Evans’s American Photographs. The book mystified him at first, with its unsentimental images of everyday America during the Great Depression. But as Szarkowski kept looking at it in his boarding-house bedroom, “it kept getting better,” raising new questions and prospects for photography that he was eager to consider.

John Szarkowski

Screen Door, Hudson, Wisconsin 1950

© The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by Scala/Art Resource NY

As a student in Madison, Szarkowski also became enthralled with contemporary art. He helped organize gallery shows at the Union, including small traveling exhibitions of paintings by Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee that came to campus from the Museum of Modern Art. And in his first job after graduation, working in Minneapolis as the staff photographer at the Walker Art Center, he was profoundly affected by seeing the radical new work of abstract expressionists, such as Karl Knaths and Barnett Newman, arriving from New York galleries.

Szarkowski’s earliest photos, including Music Hall, Madison (1943–44), taken on a melancholy, misty night while he was in college, have undeniable poetry. Yet as he matured, his photographs became more close-cropped and crisply articulated. With Screen Door, Hudson, Wisconsin (1950) and Young Pine in Aspen (1955), he gave familiar northern Wisconsin scenes their own expressionist charge. In Old Stock Exchange, Traders (1954) and Owatonna Bank, Banking Room (1954–55), two photographs of ornately decorated buildings designed by Louis Sullivan that went into his first book, The Idea of Louis Sullivan (1956), the contrast between the buildings’ sharp architectural details and the soft, rounded people inhabiting the scenes is tender and thought-provoking.

John Szarkowski

Owatonna Bank, Banking Room 1954-55

© The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by Scala/Art Resource NY

Years of writing and thinking about photography led Szarkowski to compare it to the act of pointing: “It must be true that some of us point to more interesting facts, events, circumstances, and configurations than others,” he wrote in the introduction to The Work of Atget, published in conjunction with a series of exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art from 1981 to 1985. “The talented practitioner … would perform with a special grace, sense of timing, narrative sweep, and wit, thus endowing the act not merely with intelligence, but with that quality of formal rigor that identifies a work of art.”

Szarkowski, a married father of two, retired from the museum in 1991. By then, he was ready to return to living closer to the land. He spent time at the farm he owned in upstate New York, where the weathered barns and gentle hills could easily stand in for Wisconsin. He tended his antique apple trees lovingly, and when he returned to UW–Madison in 2000 to teach a course on the history of photography, he spent spare time helping his friend and fellow photographer Greg Conniff graft new branches onto an apple tree in Conniff’s backyard. He died in 2007.

The tonally soft and spare photographs Szarkowski took in his later years — including a series of graceful desert landscapes and portraits of his apple trees in all kinds of weather — project an air of calm confidence. They also encapsulate a truth that most skillful photographers, he said, learn eventually: “the world itself is an artist of incomparable inventiveness, and that to recognize its best works and moments, to anticipate them, to clarify them and make them permanent requires intelligence both acute and supple.” •

Louisa Kamps is a freelance writer based in Madison.

Published in the Winter 2020 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.