What Superheroes Teach Us

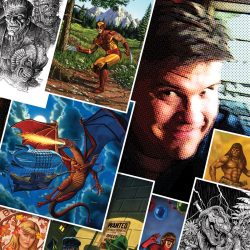

UW English professor Ramzi Fawaz shows how comic-book mutants can help readers make sense of cultural differences.

You don’t need to be bitten by a radioactive spider to gain world-changing superpowers. According to UW–Madison English professor Ramzi Fawaz, reading superhero comics can foster extraordinary abilities, such as tolerance and understanding.

This idea inspired Fawaz to write The New Mutants: Superheroes and the Radical Imagination of American Comics, his award-winning 2016 book on how comic-book superheroes of the 1960s and ’70s illustrated new forms of social belonging while wrestling with political questions raised by the civil rights movement, gay liberation, and second-wave feminism. He says mutant superheroes living on society’s margins — and more conventional characters exploring these margins, like those in Armistead Maupin’s Tales of the City — have helped readers see themselves in people who don’t share their race, class, gender, sexual orientation, or cultural background.

“Series like The Justice League of America, The Fantastic Four, and The X-Men provided readers an exceptionally diverse range of new characters and creative worlds, but most importantly, modeled what it might look like for those characters to bridge divides of race, species, kin, and kind for their mutual flourishing and the good of the world,” he argues in “The Difference a Mutant Makes,” an essay on the Los Angeles Review of Books culture blog.

A quest to promote intergalactic peace and justice fuels the divide-bridging process for many superheroes. It drives them to interact, negotiate differences, and take action together. It’s also one of the things that drew Fawaz to them, first as a reader and later as a scholar.

Origin Stories

Fawaz’s meet-cute with superhero comics involves a teleporting elf, a fighter who extracts her bones to use as weapons, and an acrobat sporting a prehensile tail. They appear on the splashy pink cover of X-Men’s 80th issue, which beckons readers with the promise of “a team reunited … a dream reborn!”

The year was 1998, and the place was Orange County, California. Fawaz was primed for transformation when he spotted that unforgettable scene on a shop shelf.

“Here I am, this gay, Middle Eastern middle-schooler living in a predominantly white area and experiencing a ridiculous amount of bullying,” Fawaz says, recalling his instant kinship with the motley crew of mutants. Though disempowerment shaped his everyday life, he identified intensely with one of the series’ most powerful characters: Storm.

“We didn’t have many obvious similarities — I’m not a woman, I’m not Kenyan, and I can’t control the weather, unfortunately — but I saw tiny pieces of myself in her,” he recalls.

Fawaz and Storm both learned how differences can make a group stronger. As his attachment to X-Men grew, Fawaz noticed how the entire series wrestled with thorny questions about diversity and nonconformity. It also inspired readers to grapple with these questions in their own lives.

According to Fawaz, comic-book superheroes of the 1960s and '70s illustrated new forms of social belonging.

When Fawaz forged his path into academia, he zeroed in on these transformative processes.

“That ability to imagine what it’s like to be someone else — someone in entirely different circumstances — is a fundamental part of being human,” he says. “We each have our own way of exercising this ability, and I think that’s beautiful.”

Students often ask Fawaz to explain the meaning of a story they’re reading. He uses this moment to discuss the power of interpretation: how readers’ experiences of a story influence its meaning in innumerable ways. What we bring to the story also matters, including our values and culture, our memories and personality traits, even what’s happening around us when we’re reading.

The imaginative space where interpretation takes place is Fawaz’s favorite intellectual playground. In his academic life, he examines how people find meaning through the lenses of feminist and queer theory, cultural studies, and literary criticism, among others.

Fawaz wants to know how popular culture can help us find alternative ways of expressing who we are, including gender and sexuality. Stories, in other words, are a tool for self-liberation as well as societal transformation.

Our Possible Futures

Fawaz began exploring such ideas during his undergraduate career at the University of California– Berkeley and at George Washington University, where he earned his doctoral degree in American Studies in 2012. He settled at UW–Madison a year later and has been collecting accolades ever since, including the Vilas Faculty Early Career Investigator Award in 2019, the Chancellor’s Inclusive Excellence Award in 2020, and the H. I. Romnes Faculty Fellowship and named professorship in 2022.

Fawaz has received numerous honors beyond UW–Madison, too. The New Mutants won an award for best first-book manuscript from the Center for LGBTQ Studies, as well as praise from academics, comics creators, and literary titans. One of those titans is Junot Díaz, author of the Pulitzer Prize–winning novel The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao.

Díaz appreciates how Fawaz uses comics — a marginalized medium — to discuss marginalized identities.

“For a long time, comics were viewed as disposable and meritless, and it is precisely in these types of cultural creations that one finds a culture’s political unconscious writ large,” he says. “Comics are the funhouse four-color mirror that reveals our society’s true face. To peer into such mirrors and not get lost requires a scholar of uncommon insight, rigor, wit, and generosity.”

Díaz says The New Mutants reveals something essential about Americans’ relationship with difference.

“Fawaz understands that our fantasies of the Other — racial, sexual, physical, gendered — are the secret fuel that powers so much popular culture. To trace these shifting, contested visions in, say, comics is to make visible our strange past and our possible futures.”

The Element of Surprise

Excelling at this kind of close reading is a bit like having x-ray vision: Fawaz sees fascinating things that have remained hidden to other readers. He uses this gift in a novel way in Queer Forms, which hit bookstores in September.

The book shows how America’s understanding of gender and sexuality has expanded to include many types of nonconformity. Fawaz supports his argument with examples from pop culture, including Armistead Maupin’s Tales of the City, a set of stories exploring friendship and LGBTQ life in 1970s San Francisco.

Though Maupin’s stories evolved into nine novels and a ’90s miniseries that stoked a firestorm at PBS, they began as a humble 1976 serial in the San Francisco Chronicle. Millions of readers grew curious about LGBTQ culture as they invested in the characters and their soap-opera adventures. Fawaz interviewed nearly 30 of these early fans, discovering how Tales shaped their relationships, actions, and identities.

He found that they were constantly in dialogue with others about what they were reading. Maupin’s narrative surprises were irresistible to nearly everyone, regardless of their station in life, and the conversations opened hearts and minds.

As Fawaz explained in a campus talk last spring, reading and other aesthetic experiences can offer a host of surprises that “catapult us into new and enlarged states of perception.” These effects can radiate through social circles, pushing people to ponder their assumptions about others.

Fawaz points to one interviewee’s account of helping her family make sense of the unfamiliar concepts in Tales of the City.

“This person and her parents had daily phone calls about these stories for two years,” he says. “She described a slow and steady transformation of her parents’ thinking, especially how her dad started out homophobic but changed along the way.”

Coming Out of the Closet

Fawaz says readers who knew little about LGBTQ culture often gravitated toward Tales’ Mary Ann, whose journey from wide-eyed Midwestern transplant to worldly woman about town is a driving force in the story. Through her, many readers learned what “coming out of the closet” meant — and what it could mean to them, no matter what their sexual orientation happened to be.

Coming out in the 1970s was “a revolutionary act performed repeatedly to reproduce and normalize queerness,” according to Fawaz, yet Tales of the City also presents it as a practice straight people could use to “forge bonds across difference.” Characters come out as all sorts of things as the story unfolds: proud gay man, transgender matriarch, and LGBTQ ally, to name a few.

The series even begins with Mary Ann declaring her devotion to something she “shouldn’t” love: San Francisco, the place her parents associate with hippies and murderers. When she announces her decision to stay there instead of returning to Cleveland, she comes out as a free-spirited adult eager to make her own decisions. She embraces how she’s different from the person her parents expect her to be.

At 28 Barbary Lane, where the landlady tapes a psychoactive welcome gift to each new tenant’s door, Mary Ann’s friends challenge her to shed her inhibitions, unleash her imagination, and find the humor in life’s inherent messiness. They also help her see herself in new ways.

Her entry into this chosen family mirrors Fawaz’s first encounter with the X-Men, which he lovingly describes in The New Mutants: “I sat by the family pool, [then] carefully opened the dazzling holographic cover; what I discovered there has kept me dreaming and made life far, far less lonely ever since.” •

Jessica Steinhoff ’01 is a Madison-based freelance writer. Her favorite superhero is mutant mind reader Jean Grey.

Published in the Winter 2022 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.