Thinking Machines

UW researchers help IBM try to create a cognitive computer chip.

Aided by input from UW scientists, IBM is developing a new generation of computer chips that aim to do something other chips cannot — think like biological brains. The company announced its first “cognitive computer chips” in August, offering the possibility that future machines will be able to perceive, correlate, learn, and act in the way that people and animals do.

Aiding in the effort are several UW scientists, including neurologist Giulio Tononi, who is advising the IBM team on how brains work, and computer engineer Mikko Lipasti, who’s adding expertise on how software and hardware interact.

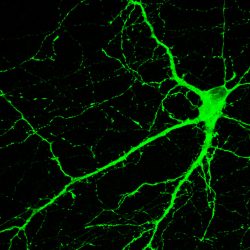

The team’s ultimate goal is to create a cognitive computer — an electromechanical device that requires as little energy as a human brain does and can replicate the abilities of a biological organ with 10 billion neurons and 100 trillion synapses. Unlike a traditional computing system, which relies on predetermined programs for its functioning, a cognitive computer would be designed to learn through experience. The goal is ambitious, and the greatest challenge may come from neurology rather than computer science.

“The whole thing gets a little fuzzy,” Lipasti explains. “We don’t have a real good understanding of how the thought processes work in a human brain, so it’s difficult to translate that into a computer. We have a good understanding of parts of it — sensory perception, for instance. So that’s what we’re focusing on now. If we do it right, we could create bold, robust control systems.”

The research is currently being funded by the Pentagon’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, and potential applications for the cognitive chip could include vision and motor control, possibly in the context of unmanned aerial vehicles. However, Lipasti says that building thinking computers could also advance our understanding of neurology — specifically, how cognition works in people.

“That’s the personal goal for me,” he says. “We don’t know a lot about how the brain works — we see the brain itself, but cognition is just this magic, secret sauce that develops over twenty or thirty years. I hope we can build a synthetic system similar enough that it will shed some light on biology.”

Published in the Winter 2011 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.