The VIP Campus Tour

A peek at UW places only insiders get to see.

It’s easy to enter the UW–Madison campus. There aren’t security gates or visitor badges. It’s practically impossible to discern where the city ends and the campus begins. A hallmark of public universities is access, and the UW is as open as they come.

But there are some limits — even here — for safety and function. And it’s those boundaries that inspired this story, an off-path tour of important UW places that most people don’t get to see. It took me and photographer Bryce Richter to every corner of campus as we walked through the Badger football team’s state-of-the-art locker room, observed the magical production of Babcock ice cream, and listened to a ringing rendition of “On, Wisconsin!” at the top of the Carillon Tower.

Join us for a trip behind the UW’s closed doors.

A Sports Sanctuary

Aside from the Camp Randall playing field, there is no space more sacred to Badger football players than the locker room. It’s where they mentally and physically prepare for action and recover afterward. The setting is also something of a social experiment for the 120 young men who cohabit the space and build a brotherhood.

But for our visit, it’s empty. The team is enjoying a short summer recess.

As we enter the locker room, we see a large trophy case. The placement is motivation fuel. The Paul Bunyan Axe and Freedom Trophy are in their rightful places, reflecting last season’s victories over Minnesota and Nebraska, respectively. The Heartland Trophy is in Iowa, leaving an empty display but a powerful message.

Nearby, a four square court is stitched into the carpet. The playground game was a popular bonding activity in the locker room prior to the safety protocols of the COVID-19 pandemic, but it hasn’t made a comeback with recent rosters. (It’s hard to compete with phone scrolling.)

The lockers are luxurious, nothing like the soulless row of steel you’d find in a gym. They were installed by the industry-leading Longhorn Lockers in 2019. The low-lit room glows Badger red, and each player’s space is identified with a large, illuminated display with his name and portrait. The locker’s surface is a three-foot-wide red, cushioned seat, which folds open to unveil ventilated storage components.

The lockers are randomly assigned, though veteran players can request the end units for a bit more comfort. Even in an empty locker room, you get a sense of the varied personalities. Some of the locker spaces are spotless to the point of looking unused, while others are littered with Gatorade bottles, granola bars, nail clippers, and rolls of athletic tape. A few lockers display photos from home along with other mementos. A large Hawaiian flag hangs in front of safety Kamo’i Latu x’25’s locker.

The shared spaces feature modern amenities that range from functional to recreational: lounge chairs, TVs, a pool table, four-foot-deep recovery pools, a saltwater float tank, nap pods, a fully equipped barber station, and a nutrition room.

“Several guys will anchor in here for hours post-practice,” says head equipment manager Jeremy Amundson ’02. And it’s easy to see why.

Sugar Central

Nearly all UW–Madison alumni share a taste for Babcock ice cream. Since opening in 1951, the Babcock Dairy Plant has produced the same recipe for its ice cream base, which includes fresh milk, real cane sugar, a gelatin stabilizer, and 12 percent butterfat. We wanted to see how it all comes together to create such an unforgettable first lick.

Visitors can follow along from an enclosed observation deck, but we’re able to view the production up close. We don food-safety coveralls in the entryway. The concrete floor is painted yellow and flooded with soapy water for sanitation purposes, a scene that reminds me of a quarantine zone from the movies. But this place is no dystopia: it’s the home of Union Utopia (vanilla with swirls of peanut butter, caramel, and fudge) and nearly two dozen other delicious flavors of Babcock ice cream.

This morning, Babcock is producing two of its bestsellers: vanilla and orange custard chocolate chip. We watch the final step of production as the base mixture, prepared at least 16 hours earlier to allow the ingredients to fully hydrate, is pumped through a specialized freezer and into packaging. The orange custard batch requires a couple of extra steps: adding the orange dye, flavoring, and egg custard base to a mixture tank and dumping chocolate chips into an ingredient feeder.

The plant received its first major renovation in 2023. A new high-flow ice cream maker with touchscreen monitors replaced original equipment, automating key parts of the production process. But we still observe manual labor: technician Joe Chamberlain positions each half-gallon container under the dispensers at a timed interval, and student workers add the lids, box the products, and send them off to the blast freezer to harden at –20 degrees. The next destination: a store or dipping cabinet near you.

I can attest to the process’s results, as I can’t help but request a scoop of orange custard chocolate chip from the nearby Babcock Dairy Store after the tour. The ice cream somehow tastes even better after I’ve seen how it’s made.

Behind the Curtain

Wisconsin Union Theater audiences are no strangers to star power. The UW could fill a hall of fame with the legendary public figures and performing artists who have taken the stage, from Martin Luther King Jr., John F. Kennedy, and Eleanor Roosevelt to Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Armstrong, and Harry Belafonte.

But few get to see the stars backstage before and after the big show. The green room and dressing room are the private areas where performers can comfortably put on and then shed their public masks.

With soprano sensation Renée Fleming on the 2021–22 schedule, the Wisconsin Union spruced up its green room with new carpeting and furniture and a fresh coat of paint. The space is a blend of casual lounge and minimalist kitchen. It’s tidy and comfortable, with wall art tracing a century of classical music performances at the venue.

On the day of a show, the green room is stocked with standard catering as well as special requests. Common items include lemon, honey, and tea to soothe a singer’s vocal cords; berries and nuts to provide a natural energy boost; and wine to wind down the night. Sometimes the contractual requests skew quirky, from wanting an on-call chiropractor to dictating the color of towels or type of ice (for example, chipped and presented in a wine glass).

The theater is home to eight dressing rooms, which allow a whole troupe to receive star treatment — even the band members backing a lead artist. “They’ll see their names on the dressing room and put it on Instagram,” says Kate Schwartz, the artist services manager.

Performers sometimes have quirky requests, including the type of ice.

But it’s still the students who tend to impress visiting artists the most. Performers will often sit down with members of the Wisconsin Union Directorate and host a studio class for a smaller audience prior to the main show.

“It’s almost like reverse celebrity, where they’re so honored to meet the students who chose them to visit,” Schwartz says. “Renée asked us, ‘How come this isn’t a model for every university?’ ”

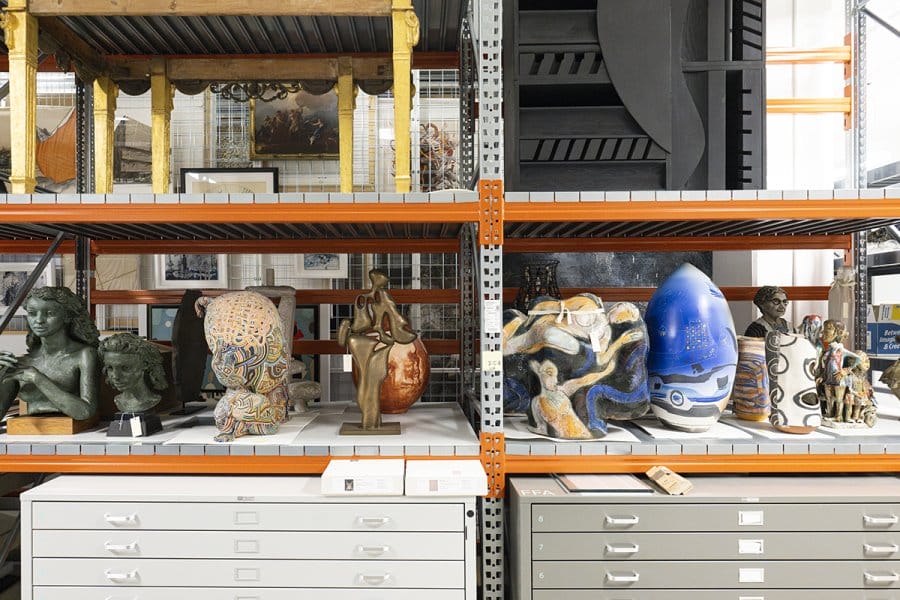

The Most Spectacular Storage

The Chazen Museum of Art’s permanent collection holds around 25,000 works. Even if you observe every piece on exhibit, you will have only seen a small fraction of its total treasures. Some 23,500 other artworks remain out of public view, painstakingly preserved in storage areas on- and off-site.

The first storage room we enter looks like an industrial warehouse. We’re greeted by open shelves containing small sculptures that could serve as an exhibition of their own. Rows of floor-to-ceiling racks reveal carefully hung artworks, suggesting the cluttered walls of an old Victorian home.

The storage rooms are strictly controlled for both temperature (70 degrees) and humidity (50 percent). When acquiring a piece, the Chazen must consider not only how it will be displayed but also how it will be stored. This often requires a customized solution. While on display, Peter Gourfain’s Roundabout is a monumental sculpture: a wooden wheel 22 feet in diameter, with 12 curving columns that rise from the base and display dozens of carved terracotta panels. But for storage, it’s been deconstructed into dozens of puzzle pieces.

“It’s a constant game of Tetris,” says Kate Wanberg ’10, the Chazen’s exhibition and collections project manager. “We move things around and consolidate to make more space.”

When acquiring a piece, the Chazen considers both how it will be displayed and how it will be stored.

Wanberg leads us to another room, this one with unframed works on paper. We can smell the ink as she opens a box with Japanese prints, each covered with protective glassine. Most artworks require the handler to wear gloves, but not these.

“You don’t want to lose the ability to sense the edge of the paper and then cause a crease,” Wanberg says. “We teach a really light touch, because you want to make sure you’re not marking the paper or transferring oils.”

If you feel like you’re missing out, fear not: the Chazen’s website features every piece in its permanent collection. And you can request an appointment to view any artwork that’s off exhibit — so long as it’s not stored in a hundred pieces.

A Keyboard on High

Lyle Anderson ’68, MM’77, the UW’s official carillonneur since 1986, laments that he can no longer give public tours of the Carillon Tower on Observatory Drive. An engineering survey a few years ago deemed that the steep, winding staircases are too risky for visitors. The carillon is played atop the tower to unseen passersby 85 feet below — just Anderson and his 56 bells, ranging in size from 15 to 6,823 pounds.

But today, we’re an exception, allowed to join him for a trek up the tower and an impromptu concert. The tower was built in 1935 with just 25 bells, limiting the musical range to simple melodies. We see the large trapdoors on each floor that allowed new bells to be winched up until the carillon’s completion in 1973.

The carillon is played atop the tower to unseen passersby 85 feet below.

The stairs are as advertised, especially an original section — basically a ladder — between the playing room and the bell chamber. The four-limbed climb is worth it when we see the bells in all their glory. Perfectly aligned rows of smaller bells hang in front of the bronze giants. Lightbulb-shaped clappers rest inside the bells, connected by wires to the keyboard and ready to strike.

Anderson serenades us with “On, Wisconsin!” It’s mesmerizing to see each note mechanically register with the corresponding bell. For “Amazing Grace,” he pushes down wooden batons with the sides of his fists while thrusting his feet at the levers.

“The newer generation plays a lot more with their fingers, almost like a piano,” Anderson says. “My teacher from carillon school 40 years ago would have been absolutely appalled.”

Anderson technically retired in 2016, but he still climbs the Carillon Tower every other Sunday for an hourlong concert. Where’s the best place to listen?

“The courtyard out front or across the street,” Anderson says. “If you get too far, buildings will block the sound, and traffic will make a lot of noise coming up the hill. But it’s an outdoor, urban instrument, so that’s just part of the show.”

Where the Cows Come Home

You rarely see — or smell — a dairy farm in the heart of a metropolis. But at the flagship university in America’s Dairyland, college students share the campus with cows. The Dairy Cattle Center on Linden Drive is hard to miss, its pair of silos piercing the city skyline and its farmstead odor detectable for blocks.

The UW’s on-campus herd comprises 84 Holstein milking cows, split into two tie-stall barns. They’re milked twice per day, at 4 a.m. and 4 p.m. Local co-op Foremost Farms picks up the milk, occasionally delivering it to the nearby Babcock Dairy Plant for campus production of cheese and ice cream.

The herd’s primary purposes, however, are for instruction and research. The Department of Animal and Dairy Sciences and the School of Veterinary Medicine hold classes at the facility, where students learn how to interact with the cows and provide care. Research projects include animal welfare, food safety, and land stewardship.

Built in 1954, the Dairy Cattle Center has been renovated over the past decade to modernize its operations. Keeping the farm functioning requires four full-time staff members and a dozen or so students, including three managers who live on-site and conduct nightly rounds.

After putting on disposable shoe covers, Bryce and I enter the first barn and slowly approach the cows. It’s not hard to sort the friendly ones from the shy ones. Some take a step back or shake their heads, a simple fear response that to us feels like stinging rejection. Others crane their necks toward us for attention, and we eagerly oblige. Stella takes a particular liking to Bryce, gently chomping his hand as if it were hay. When he points his camera for a close-up, she curiously smells the lens, covering it in snot and ending our photoshoot in memorable fashion.

The Inner Sanctum

“The chancellor is ready for you.”

With that, we suddenly know what it feels like to meet with a very important person. And since we’ve fashioned this as a VIP tour, the most appropriate place to end it is at Chancellor Jennifer L. Mnookin’s office in Bascom Hall, where UW–Madison’s most important decisions are made.

The grand space leaves you with little doubt of its standing. The high, ornamental ceiling sets the room’s consequential tone. Classical moldings frame the arched windows and every wall, with craftsmanship harking back to Bascom Hall’s 1850s construction. A marble fireplace with columned trim anchors the room.

The spacious office is split functionally into three sections. As you enter, there’s a conference table for small-group meetings. The middle of the room can host more casual conversations, with a red velvet couch, coffee table, and upholstered chairs. (After laboring to move the chairs for a photo, we can confirm the furniture is made of real wood and is not from IKEA.) Mnookin’s L-shaped workstation is at the far end, flanked by built-in bookshelves with a sizeable collection of law books, including her own works.

In true Badger fashion, Mnookin balances the regal setting with playful touches, including a mini Terrace chair, a foam pink flamingo, and a Bucky piggy bank. She doesn’t hesitate when I ask whether she has a favorite object: “The photos of my family.”

In true Badger fashion, the chancellor balances the regal setting with playful touches.

Mnookin’s job takes her around the campus, the state, and sometimes the world, so there’s no guarantee that she’ll be at her desk on any given workday. When she is, the usual tasks include “answering emails, reading memos and documents, and thinking through both immediate needs and bigger-picture strategic questions,” she says.

And yes, the chancellor has to hike up Bascom Hill, just like the rest of us.

“As long as it’s not freezing cold,” she says, “I appreciate earning a few steps at work.”

Preston Schmitt ’14 is a senior staff writer for On Wisconsin

Published in the Fall 2024 issue

Comments

Guang Rong September 28, 2024

Some many interesting places but I missed many of them during my two year, 81-82, stay in UW Madison.