The Magnificent Magnus Swenson

The UW’s first prolific inventor was also a visionary businessman and humanitarian with an outsized impact on the world around him.

As Madison’s population began to grow in the 1860s and 1870s, its residents increasingly suffered from outbreaks of typhoid fever, cholera, and other diseases that particularly ravaged the city’s children.

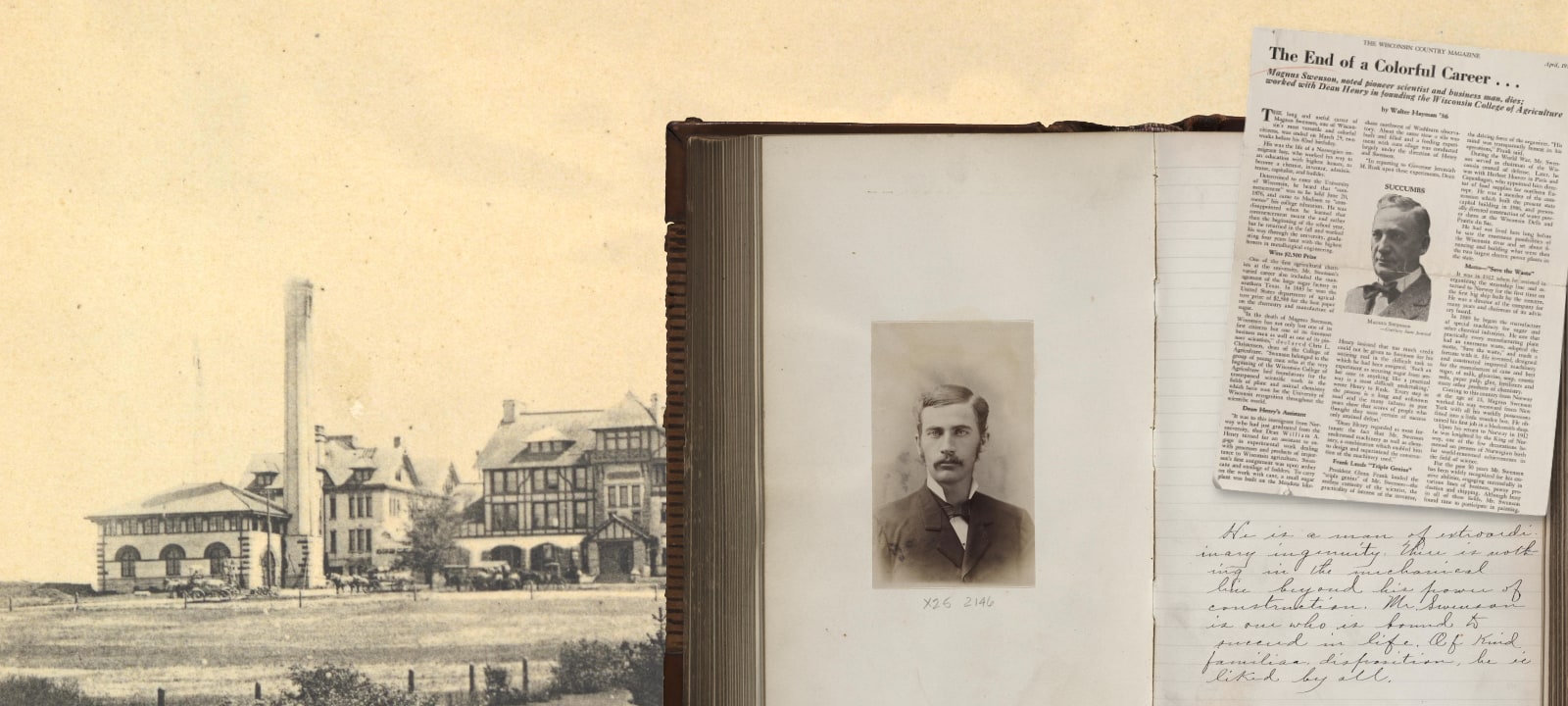

UW undergraduate Magnus Swenson 1880, MS1882 had a hunch about what was causing the lethal infections. He soon initiated what Madison historian David Mollenhoff MA’66 believes was the first instance of a town-gown collaboration.

The engineering student did his senior thesis on the quality of Madison water, claiming that 96 percent of it was unfit to drink. The city’s residents had private wells and privies, often located within mere feet of each other, and they did not yet connect diseases such as typhoid with contaminated water. As Swenson took samples for his study, insulted citizens pelted him with stones and bottles, requiring a police escort.

To help Swenson complete his analysis, the Common Council encouraged him to set up a lab in the basement of the capitol — the predecessor to the Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene. Soon after that, Madison had a central artesian public water supply and a sewage system.

“To the restless curiosity of the scientist, he added the practicality of interest of the inventor and the driving force of the organizer.”

It was the first of many remarkable achievements for Swenson. Although the Wisconsin newspaper archive has some 2,200 entries about him, few people today have heard of him. And that is partly by design. The Norwegian immigrant cared little for getting personal credit or attracting attention to himself.

Yet he was a textbook example of the Wisconsin Idea, even before the concept officially existed, since he used the knowledge he gained at the university to benefit the city, the state, and the world.

Not bad for an impoverished boy who emigrated from Norway at age 14, narrowly escaping death.

Overcoming Stormy Seas

Swenson was born in 1854 in Langesund on the southern coast of Norway. His mother died when he was two, and he suffered neglect and occasional abuse at the hands of his stepmother. When Swenson was 14, his father’s rope factory burned down, so he and his two older brothers boarded the small ship Victoria for America to seek their fortune. Bad weather delayed their arrival, and provisions for what should have been a six-week journey ran out as storms tossed the now rudderless vessel about for 12 weeks. Swenson often escaped the misery on deck by curling up in the crow’s nest. Twenty-two of the 60 passengers died of starvation and exhaustion, and Swenson weighed only 48 pounds when he got off the boat on Anticosti Island in Quebec.

Swenson and his brothers made their way to Janesville, Wisconsin, where they lived with an uncle and aunt while recovering from their ordeal. Swenson attended school to learn English, and once he regained his strength, he became an apprentice to his uncle, who was the foreman in the blacksmith shop of the Northwestern Railroad. There he mastered multiple aspects of metalworking and was promoted to mechanic.

While Swenson was sharpening tools for workers who were building a bridge over the Rock River, he decided that he, too, wanted to become an engineer. So he came to Madison in June 1876 during commencement, only to find that commencement actually marked the end of a college career, not the beginning. But he returned to campus in the fall and threw himself into earning a degree, graduating with honors in metallurgical engineering.

Early on, Swenson manifested a relentless drive for efficiency. During a summer job surveying for a proposed railbed in the Dakotas, he noticed that his pack mule took even steps and virtually never deviated from its straight-line course. Instead of measuring the ground, Swenson decided to measure the mule’s step, and he and his partner took turns riding the animal and counting its paces. The two young men covered territory much more quickly than other surveyors, and it wasn’t until 50 years later that their technique was found out. Amazingly, when the roadbed was measured again decades later, the mule measurements were found to be accurate to within a fraction of an inch.

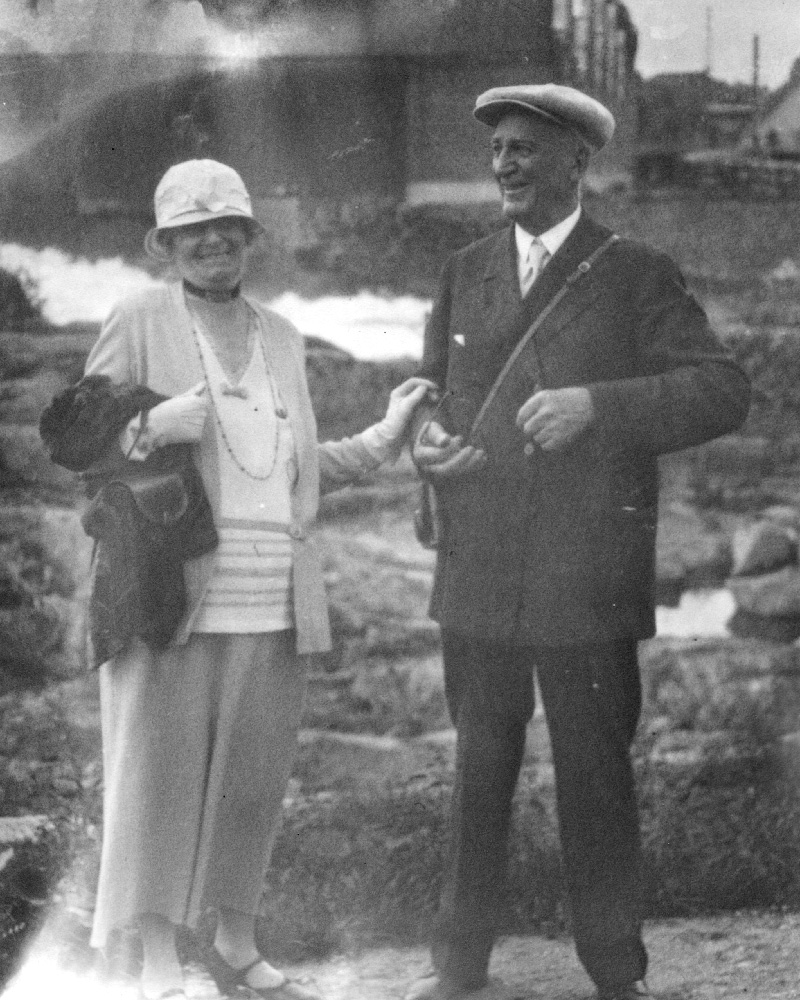

Swenson met his wife, Annie Dinsdale, at a class in the UW’s Washburn Observatory. The couple are shown during one of their trips to Norway. Photo courtesy of Mary O’Hare Lewis

Swenson met his wife, Annie Dinsdale 1880, MA1895, at the UW during an astronomy class at the Washburn Observatory. She had fainted, and the chivalrous Swenson carried her outside for some fresh air. They encountered each other again at a UW picnic and were soon engaged. Their marriage lasted for more than 50 years, and his letters attest that even decades later, he was still very much in love with her.

Leonardo-Level Inventor

After graduating, Swenson taught chemistry for three years at the UW. He helped found the College of Agricultural and Life Sciences (CALS) along with William Henry, the college’s first dean, and the pair served as the first two faculty members of the college, which had only two students in its first year.

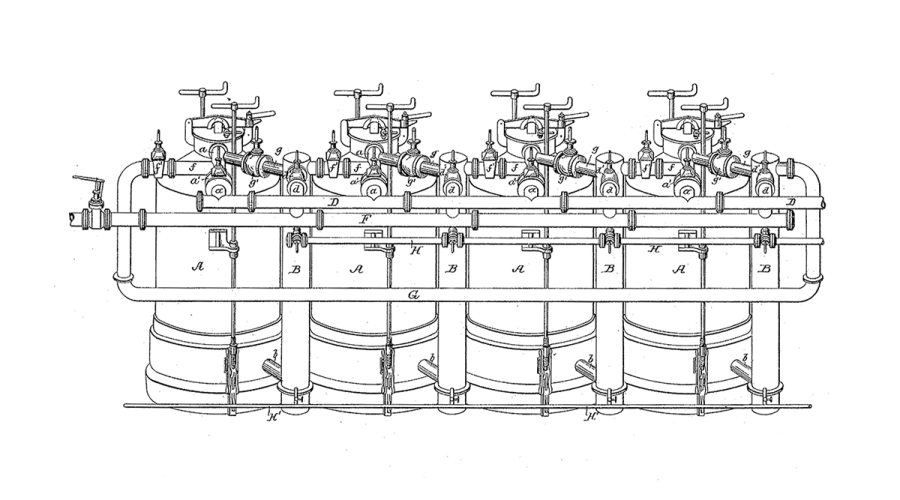

Their first research project sought to improve processes for extracting sugar from sorghum. Swenson proved adept at combining chemistry and engineering before chemical engineering was even recognized as a field. His thesis on the chemistry of sugar won him a $2,500 prize from the USDA and an offer of a job running a sugar plant in Texas. Following a public experiment with a faulty centrifuge that sprayed sorghum molasses all over 400 of Madison’s leading citizens and local farmers, Swenson concluded it was a good time to leave town.

In his first year on the job, Swenson doubled the Texas plant’s output. He went on to design machinery that revolutionized the sugar industry, improving cane and beet processing so much that he became known as the Eli Whitney of sugar.

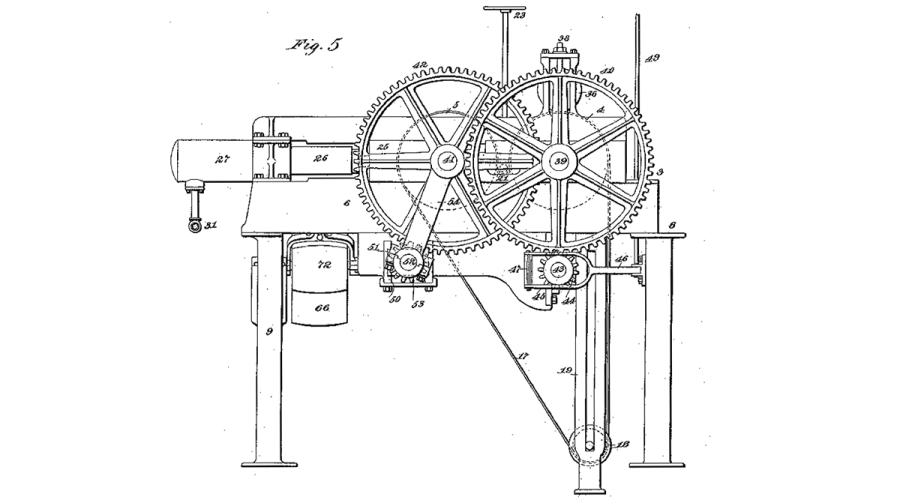

Swenson then turned to manufacturing all sorts of industrial equipment, and he set up factories in Kansas and the Chicago area. He was best known for his evaporators, which significantly improved manufacturing processes and were shipped all over the world. He invented a mining ore concentrator that became industry standard, as well as a cylindrical cotton baler, achieving a goal that had eluded the cotton industry for 50 years.

He also designed improved equipment and processes for the manufacture of soap, caustic soda, glycerin, glue, paper pulp, fertilizers, tobacco, pharmaceuticals, and other products. He even invented one of the first “horseless carriages.” After moving to Chicago, he turned his attention to ways to utilize waste byproducts, serving as a consultant to the meatpacking industry and to companies such as Procter & Gamble, Swift, and Colgate. His motto was “save the waste,” and conserving resources was a hallmark of his career. According to the Wisconsin Engineer magazine, he visited multiple plants around the country and encouraged manufacturers to install waste-saving devices.

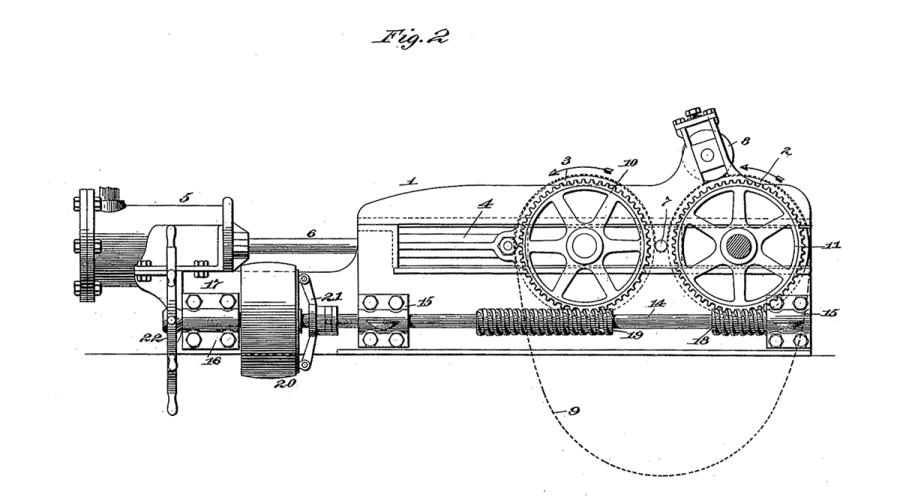

Diffusion Battery, patented June 24, 1890, by M. Swenson

Cotton Baling Press, patented Sept. 26, 1899, by M. Swenson

Cotton Press, patented Feb. 5, 1901, by M. Swenson

Although Swenson was awarded more than 200 patents in 10 years for various machines and processes, according to his biographer, UW chemical engineering professor Olaf Hougen PhD 1925, “He willingly turned over his inventions and his factories to others, without much regard to adequate compensation or credit. … He was interested in theory only insofar as it could be applied to practical uses.” Once he had mastered a machine or process, Swenson moved on and rarely even bothered to document his methods. Hougen credits this extreme pragmatism for Swenson’s exceptionally productive career.

Civic and Business Giant

By 1902, Swenson was wealthy, and he moved with his wife back to Madison so that their four daughters could attend the UW. But he couldn’t stay retired for long. He soon proved to be as proficient at civic work and business as he had been at science and invention.

In 1905, he chaired the building commission for the Wisconsin state capitol. The black labradorite stone at the base of the columns in the rotunda came from Larvik, Norway, “a bit of Swenson’s sentiment to the place of his birth,” according to Hougen. That same year, Swenson was named to the UW Board of Regents and served for 15 years, 10 of them as president. He was also instrumental in creating the UW’s Department of Chemical Engineering in 1905 and served on the building committee for the university’s Memorial Union.

Recognizing an underutilized resource in the Wisconsin River, Swenson financed and built the first hydroelectric plants west of Niagara Falls at Wisconsin Dells and Prairie du Sac, saving 200,000 tons of coal annually. Lake Wisconsin, created by damming the river for the plant in the Dells, was originally named Lake Swenson.

He also became president of the Norwegian-American Steamship company, returning to Norway for the first time in 1912 on the first steamship that the company built. According to his friend C. J. Hambro, Norway’s representative to the League of Nations, Swenson was so overcome with emotion to see his homeland again that “he threw himself on the soil of Norway and kissed it and wept.” During the visit, the king of Norway made him a Knight of St. Olav for his contributions to industry and science.

Like many successful entrepreneurs, Swenson could have a prickly side. He often clashed with his former classmate Robert “Fighting Bob” La Follette 1879, LLD 1901, the storied Wisconsin governor and senator. When La Follette requested that Swenson, in his role as regent, remove Dean Henry from the agricultural college, Swenson asked if Henry had been inefficient. Upon being told no, Swenson said, “Well, then he remains, and so do I. I am not here to do your bidding.”

Both Henry and Swenson kept their posts.

Impressive on the World Stage

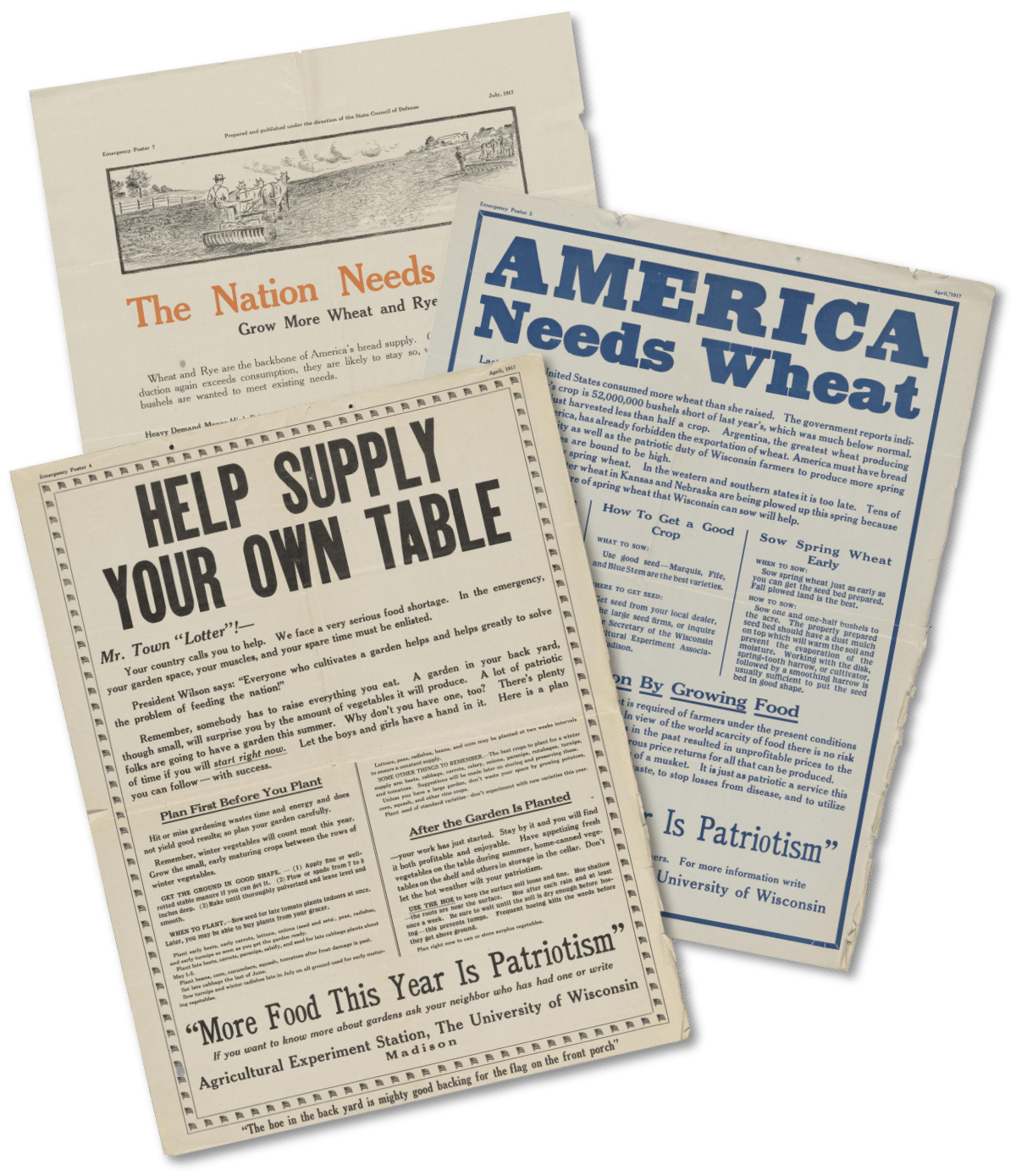

During World War I, Swenson chaired the Wisconsin State Department of Defense in an unpaid position. His organizational talents soon earned him a role as federal food administrator for Wisconsin. He encouraged citizens to grow gardens and observe meatless and wheatless days, making the state a leader in the efforts to conserve food for the war effort. His strict enforcement of food laws caused big businesses to try, unsuccessfully, to oust him.

Swenson’s introduction of Wisconsin food conservation measures, such as meatless and wheatless days, became a national model used during both world wars. UW Archives

When future U.S. president Herbert Hoover was named national food administrator, he adopted many of Swenson’s ideas. The measures that Swenson developed in Wisconsin not only guided national efforts during the First World War, but they also became a model for food conservation during World War II. When Hoover became the director of postwar relief in Europe, he chose Swenson to distribute food aid to the Baltic countries, and the two remained good friends for the rest of their lives.

Swenson threw himself into relief work, perhaps due to his own experience with hunger. In Denmark, according to Hougen, the Danes admired the “tall, stately man with gray hair and blue eyes. … They marveled at his capacity for getting things done.”

When the American Relief Administration arrived in Libau, Latvia, with food supplies, the Copenhagen press reported that “it encountered complete chaos and the most abject helplessness on the part of the populace.” It seemed impossible to find any way to transport the desperately needed food. But Swenson was undeterred. When asked how he planned to distribute the supplies, one news report marveled, Swenson calmly answered, “‘By building a railroad.’ And in an incredibly short time, the road was completed and relief trains departed regularly for stricken parts.”

Under Hoover’s orders, Swenson bent the rules to get food to starving people. He ignored official ports of entry, and when other countries became indignant, Hoover sent a telegram in code saying: “Lie about everything. Keep food moving.” When Swenson discovered that the Swedish government was engaging in price gouging with American-supplied salt pork, he reported it to the press, which resulted in an immediate end to the practice.

But Swenson focused his initial efforts on Finland, which was the hardest-hit country. When he arrived, 60 percent of Finnish children had already died. In a letter to Wisconsin governor Emanuel Philipp in 1919, Swenson wrote, “The people of eastern and northern Finland have been subsisting almost entirely on bread made from the inner bark of trees and ground birchwood. … I think I am not overstating the case in saying that one-half of the population of Finland would have succumbed and the other half reduced to extreme weakness had it not been for the help that we were able to give them.”

When Swenson left, the grateful Finns declared a national holiday and feted him with music and bouquets of roses, moving him to tears.

An effort to respond to a Russian request for food aid did not go as well. Swenson negotiated with dictator Vladimir Lenin on behalf of Hoover, but Lenin angrily refused to meet Hoover’s terms, instead responding with a lengthy telegram directing abuse at Hoover and America.

While Swenson was admired for his ironclad integrity, Hambro said that he could be “hard to manage” in his service to what he saw as the truth. Swenson once defied a request from Hoover and President Woodrow Wilson to retract a statement that England had been unfair in its policies toward the Scandinavian countries. Swenson worked with an editor to craft a retraction, but in the end, he just couldn’t do it. “I will not correct that which everyone knows to be true, and I know that Hoover will agree with me,” he said.

Triple Genius

When Swenson died in 1936, the UW awarded him an honorary doctorate, his third UW honorary degree. “To the restless curiosity of the scientist, he added the practicality of interest of the inventor and the driving force of the organizer,” UW president Glenn Frank said in a eulogy. “To this hour the tradition and service of the college of agriculture bear the marks of this triple genius he brought to its early development.”

Swenson’s legacy lives on — not only as the originator of the industrial-efficiency movement but also in CALS and the Wisconsin River, in Madison’s water system, and in generations of Scandinavians whose ancestors survived because of his relief efforts. Swenson House in the UW’s Kronshage Residence Hall is named after him, and his Madison estate on Lake Mendota, Thorstrand, still stands.

But his name (Magnus appropriately enough means great or the great in Latin) is slowly fading from memory. A street off Thorstrand Road once called Magnus Swenson Drive was renamed in 1995. Circumstances have conspired to obscure our collective debt to this larger-than-life alumnus. But knowing how much his efforts helped to shape future generations probably would have been enough to move him to tears all over again. •

Niki Denison is coeditor of On Wisconsin.

Published in the Spring 2025 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.