The Fight for Title IX

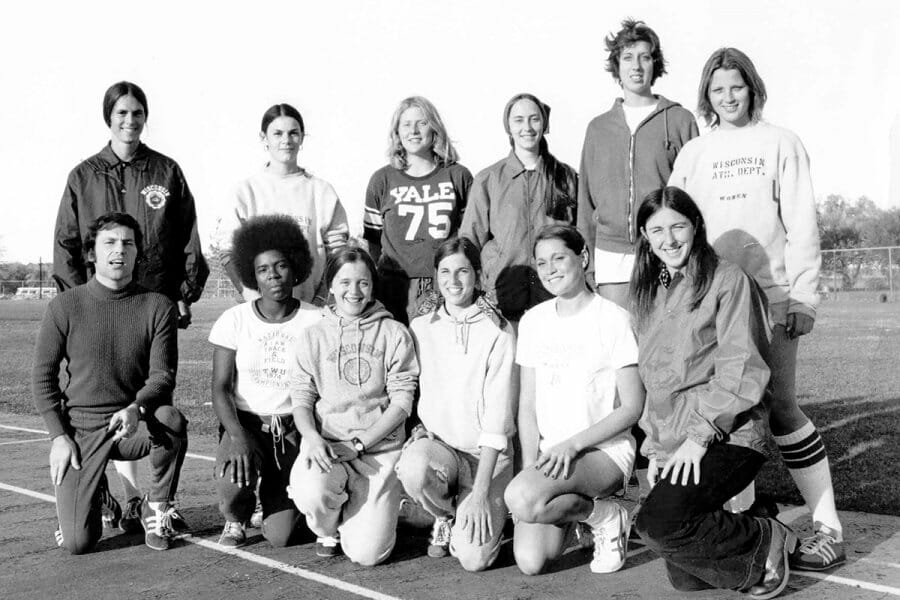

Fifty years ago, Kit Saunders MS’66, PhD’77 ushered in a new era for the UW’s women athletes.

This excerpt is adapted from the book The Right Thing to Do: Kit Saunders-Nordeen and the Rise of Women’s Intercollegiate Athletics at the University of Wisconsin and Beyond (HenschelHAUS Publishing). It deals with the passage of Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, which prohibits sex-based discrimination in education activities and programs receiving federal funds. Saunders-Nordeen (known as Kit Saunders earlier in her life) became UW–Madison’s first athletic director for women and also served nationally as vice president of the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women. She retired from the UW in 1990 and died last year at age 80.

President Richard Nixon signed the bill into law on June 23, 1972. It was a momentous development for women’s college athletics that was not widely realized as such at the time. Other parts of the Education Amendments of 1972 — busing, financial assistance — received more attention. Title IX landed with a whisper.

Still, it was noted in Madison by Kit Saunders MS’66, PhD’77, who, as women’s sports coordinator for the UW club sports program, had been trying with scarce resources to get a women’s athletics program going.

“I can remember first hearing about Title IX being passed and thinking, ‘Oh, boy, somebody finally did something,’ ” Saunders recalled. “ ‘This is probably going to help us.’ ”

And Saunders needed help. She described the landscape for women’s athletics on campus, pre-Title IX, in a UW Oral History Program interview.

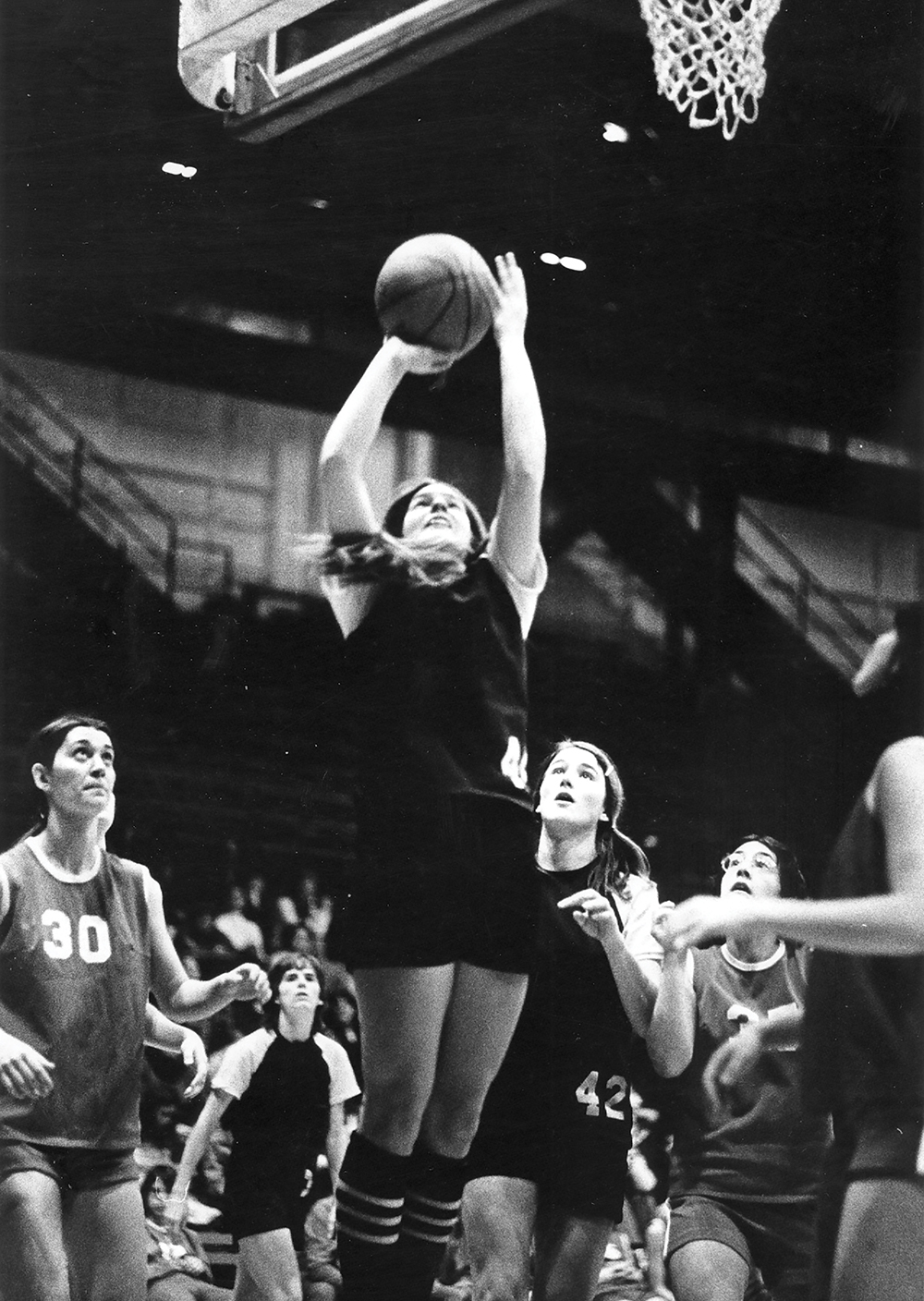

“We were not able to pay our coaches very much at all. … Students did have to pay some of their expenses if there were overnights. Male athletes even in non-income sports were getting their ways paid completely.

“We had no priority on facilities,” Saunders continued. “If a facility was available, wasn’t being scheduled for something else, including intramurals and in some cases open basketball shooting, then we could get it. We were practicing in Lathrop Hall, which had no regulation-size [basketball] courts. Our swimming practices — we had one evening a week in the Natatorium.

“We had very limited uniforms. We had about two dozen warmup suits, and with 11 teams going at once, we called it ‘musical warmups.’ We’d have to try to launder them quickly and get them to the next team. We didn’t have any kind of laundry service. The coaches frequently were doing the laundry, or the athletes were doing it themselves.”

As women’s sports coordinator, Saunders had to go in front of the intramural recreation board each year to request funding. The passage of Title IX in 1972 may have emboldened her — for 1972–73, the women’s program received $8,000, four times the previous year’s budget, if still a pittance in comparison to the men.

“These meetings were frequently harrowing experiences,” Saunders noted. “The women’s program was wearing out its welcome in the club sport program as it became more expensive and more closely resembled an intercollegiate program.”

For 1973–74, when Saunders requested $25,000 to run her growing program, she was allocated only $18,000.

“So I went to the chancellor [Edwin Young PhD’50] and told him I was short,” she recalled. “He came up with that for us.”

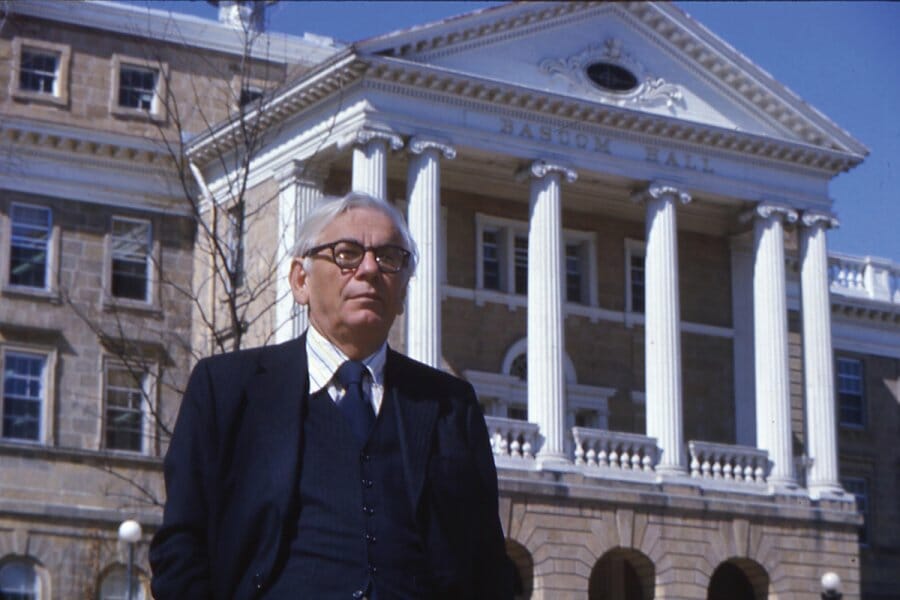

Presumably with Title IX on his radar, Chancellor Young, in July 1972, appointed a committee to study women’s athletics and make recommendations on how they might be better served on campus. But the committee included no UW women student-athletes. And Young seemingly erred in his choice of Athletic Director Elroy Hirsch x’45 as committee chair. Hirsch called only two meetings between July 1972 and March 1973, and the second meeting was canceled.

This so infuriated a member of the committee, Muriel Sloan PhD’58, chair of the women’s physical education department, that on March 2, 1973, she sent Hirsch a blistering letter, threatening to resign from the committee.

“For me to remain on this inactive committee,” Sloan wrote, “is to continue the illusion for women students and interested faculty groups that the problem of facilities for women is being seriously considered. … You can see, therefore, that my membership on this nonfunctioning committee and its nonfunctioning status is untenable. I would prefer that the committee begin to function rather than resigning from it. If, however, you as chairman and other committee members are not equally devoted to pursuing the committee charge, then all should disband. A new committee could then be appointed by the chancellor, or existing groups concerned with equal opportunity on campus can follow up on their expressed interest in the issue.”

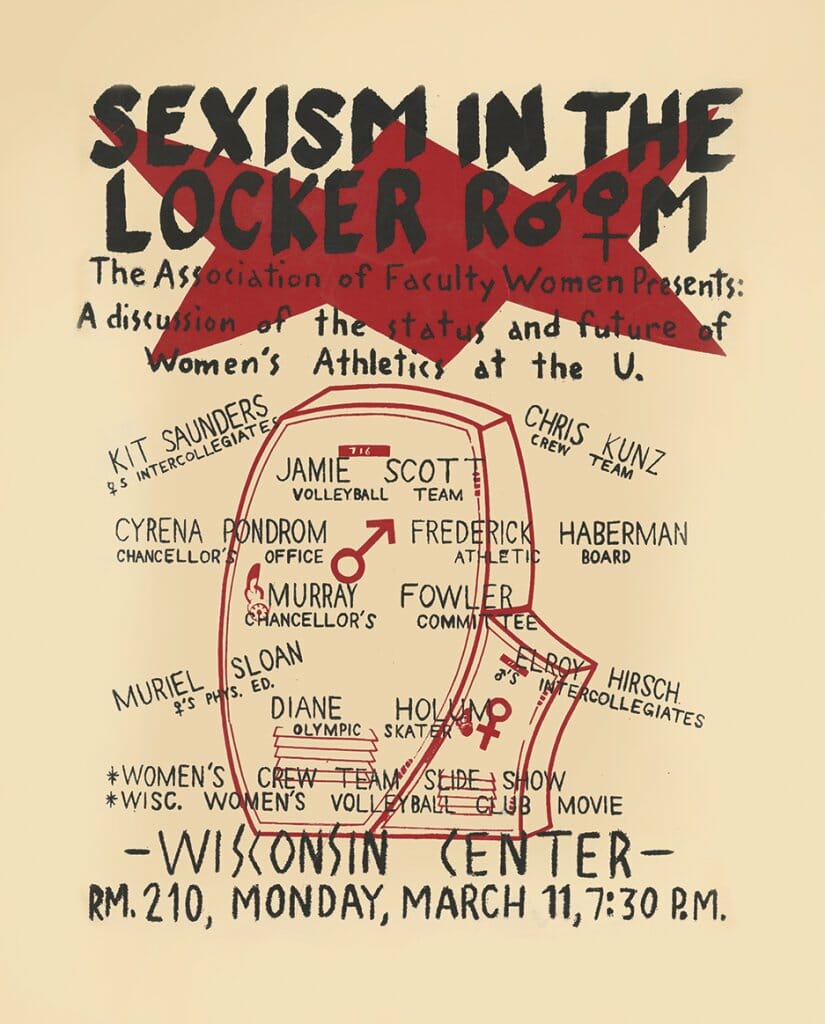

A poster for a 1974 panel discussion that descended into boos, hisses, and angry shouts. UW Archives 2017S00257

Sloan was formidable, a New York native who came to Madison for graduate school and stayed. She also served as vice president of the International Association of Physical Education and Sport for Girls and Women.

We’d love to hear your stories of UW women’s athletics from pre-Title IX to today. Email us at onwisconsin@uwalumni.com; send a letter to On Wisconsin, 1848 University Ave., Madison, WI 53726; or leave a comment on this article.

Equally formidable on the Madison campus in 1973 was Ruth Bleier, who joined the UW’s department of neurophysiology in 1967, embarking on a career that included a deep dive into gender biases in science. Bleier was a founding member of the Association of Faculty Women at UW–Madison, and it was in that role, two weeks after Sloan wrote her letter to Hirsch, that she followed with one of her own.

Bleier began her March 16 letter by noting the antidiscrimination law that now existed under Title IX, and then wrote:

“Consequently we demand immediate and equal use of all facilities: tracks, fields, courts and pools, locker rooms, and showers. This means that all facilities be available to women and women’s teams at times that are no more inconvenient for them than for men, such as dinner time for the tennis courts and after 5:30 p.m. for the track team, the periods currently allowed women.

“We demand adequate and equal (as needed) funding for all women’s sports teams,” Bleier continued, “including salaries for coaches with full-time academic appointments and expenses for training and competition. Anything less than this must be negotiated with us and other women in athletics and justified to our satisfaction. We do not want to hear again about inadequacy of facilities, space, and time. If they are inadequate, we will share equally with men in the inadequacy. The burden is no longer ours to wait. We have waited too long. The moral and, now, the legal burden is yours.”

Hard to mistake a gauntlet being thrown down there.

One can imagine Saunders finding herself in a somewhat delicate circumstance. While she no doubt sided with Sloan and Bleier, she was also operating inside the athletic administration umbrella. Vitriol would not serve her purpose and was not her style, in any case.

“I remember after [Title IX passed], trying to explain it to the athletic board. I’d really learned about it and what it stood for — what we were going to have to do,” Saunders recalled. “People had refused to act because they didn’t have enough information. The women who had become versed in it were trying to tell [various administrators] what it was. And they were saying, ‘This can’t be.’ ”

Bleier: “We do not want to hear again about the inadequacy of facilities, space, and time. … We have waited too long.” UW Archives S05706

On April 3, 1973, a complaint against the University of Wisconsin was filed with the United States Department of Health, Education, and Welfare’s Office of Civil Rights.

“The University of Wisconsin, Madison campus, is in flagrant violation of Executive Order 11246 [a 1965 nondiscrimination order issued by President Lyndon Johnson] and of Title IX … in its continued provision of unequal facilities and funding for athletics programs for women students and employees and unequal compensation for the coaching of its women’s teams.”

"We demand immediate and equal use of all facilities," Ruth Bleier wrote to the UW committee on women's athletics in 1973.

In Madison, Saunders and her colleagues were grateful for signals from Washington that Title IX would be enforced.

“The sort of sad thing about Title IX,” she said, “is that most schools began to comply not because it was the right thing to do and had gotten started anyway, but because they were worried about the teeth that were in it and what the federal government could do. Like take away their federal funding and lots of other types of programs.”

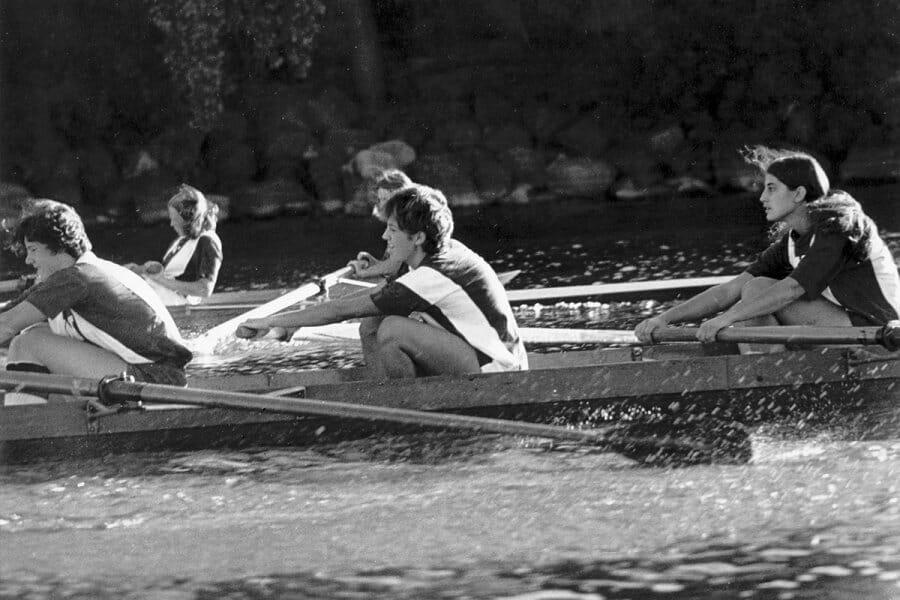

In conjunction with the 50th anniversary of Title IX, the UW athletics department is raising $2 million to support women’s crew, in honor of longtime coach Sue Ela. There are nearly 4,000 women’s rowing alumnae.

On April 19, Chancellor Young stepped in and replaced Hirsch as chairman of the Committee on Women’s Athletic Programs and Facilities with Murray Fowler, from the Department of Linguistics. Young wrote a letter to Fowler stating his hopes.

“This committee,” he wrote, “is charged with advising me of the most appropriate ways to achieve equity in men’s and women’s recreational, intercollegiate, and intramural athletic and physical education programs and facilities on the Madison campus.”

Unlike Hirsch, Fowler moved quickly. By May, the committee had passed a recommendation requiring that “all physical recreation facilities administered by the University of Wisconsin should be made available for use by both men and women.”

The most likely home for an intercollegiate women’s program was inside the UW athletics department. The athletic board took a step in that direction in September 1973, during a meeting that the Wisconsin State Journal reported “opened the door to women’s intercollegiate athletic competition within the framework of the Department of Intercollegiate Athletics.”

“The board did not immediately invite the ladies inside,” wrote State Journal sports editor Glenn Miller in his inimitable way. “Still, it was a historic step.”

What the board did was insert the following into its policy book: “It is the policy of the athletic board to make intercollegiate athletic competition, facilities, finances, administrative resources, coaching, and ancillary personnel available to all qualified undergraduate students without regard to race, creed, religion, national origin, or sex.”

The Fowler committee was meanwhile formulating its own recommendations. The women members — who included Saunders and Sloan — presented a proposal to the full committee in December 1973. The committee accepted the proposal in its entirety, with Fowler saying that it would be up to Chancellor Young to act on it. A highlight among the committee’s recommendations was this:

“We believe that combining athletic programs [men’s and women’s] will be beneficial from the outset for women’s athletics and in the long run also for men’s athletics in the educational setting of the university.”

And this:

“That a woman whose title shall be director of intercollegiate athletics for women shall be responsible directly to the director of intercollegiate athletics.”

Chancellor Young took the Fowler committee’s recommendations and handed them to the athletic board, telling board chairman Fred Haberman to develop a plan of action, which some saw as the chancellor punting the issue, to use a sports metaphor. Haberman responded by appointing a committee to study it.

It was contentious, and Saunders, as ever, was a voice of calm. She gave an interview to the State Journal, stressing how well she got along with Otto Breitenbach ’48, MS’55, Hirsch’s top assistant.

“Our philosophies are similar,” she said.

The uncertain status of Title IX nationally couldn’t have helped. It had taken months to wake up, but the male college sports establishment — exemplified by the executives who ran the National Collegiate Athletic Association — was sounding a five-alarm alert. In numerous interviews, these men predicted doom if the Title IX regulations were enforced.

As the first director of UW women's intercollegiate athletics, Saunders led the way to "an exciting future."

On March 11, 1974, an extraordinary panel discussion took place at the UW’s Wisconsin Center. Its stated purpose was to review the progress of women’s athletics on campus.

Members of the panel included Saunders, Hirsch, Fowler, Sloan, assistant to the chancellor Cyrena Pondrom, and four women student-athletes.

That the evening would be lively was assured by the moderator: Ruth Bleier, whose letter to Hirsch a year earlier had demanded equity for women’s athletics.

Fred Milverstedt ’69, a young sports columnist for the Capital Times, didn’t mince words when it came to the reaction to Hirsch’s comments: “Most everything he said subsequently was greeted with hissing, boos, some subdued cursing, and occasional angry shouts.”

Somehow — quite possibly owing to Saunders’s unflappable, behind-the-scenes work — the campus went from that raucous affair to another, vastly different gathering less than two months later.

On May 3, 1974, a news conference was held in which Hirsch and Haberman announced the first director of women’s intercollegiate athletics at the University of Wisconsin.

It was Kit Saunders.

That it could hardly have been anyone else did not lessen the excitement.

Saunders told reporters that while there was “a great deal of work to be done,” women’s athletics at the UW had “an exciting future.”

As usual, Saunders wasn’t wrong. She started her new job on July 1, 1974. Within a year, she had a national championship in women’s rowing. •

Doug Moe ’79 is a longtime Wisconsin journalist and the author of numerous nonfiction books.

Published in the Summer 2022 issue

Comments

Wayne Arnold July 9, 2022

Great story by the ever-excellent Mr. Moe. All of this change was long overdue and past practice seems ridiculous in hindsight. Do wish men’s baseball could have continued…