Surprising Stories from UW Archives

These unusual artifacts shine a light on campus history, from lost traditions to lesser-known heroes.

History doesn’t just happen. It’s created through the stories we tell and the way we tell them, the details we choose to include and the ones we edit out. Our biases and blind spots shape this process, as do the artifacts we save for future reference.

Katie Nash considers all of this when deciding what to add to UW–Madison’s Archives. It’s one of her many jobs as head archivist. Organizing massive amounts of information and making it accessible is another. Then there’s preserving the materials, an epic battle involving dust, fragile objects, and obsolete technologies. She even helps researchers like me.

“Looking at the past can help us move to a more proactive place in the present, one where we can make informed decisions for the future,” she says.

That’s why Nash and her team — nine employees and more than a dozen student assistants — view public education and research support as their primary roles. Each year, they help thousands of visitors connect with the people, places, and problems of the past.

My mission for this article was simple: find unexpected and under-the-radar items in the UW Archives collections, spanning campus history. On the occasion of the university’s 175th anniversary, here are essential artifacts that tell surprising stories about the UW–Madison experience, from the tragic to the triumphant.

When Mandolins Were Cool

Pre-internet and pre-television, what did college students do for fun? Make music, according to scrapbooks from UW–Madison’s first century. Before there were rock bands, vaudeville-inspired mandolinists were the cool kids on campuses throughout the Midwest.

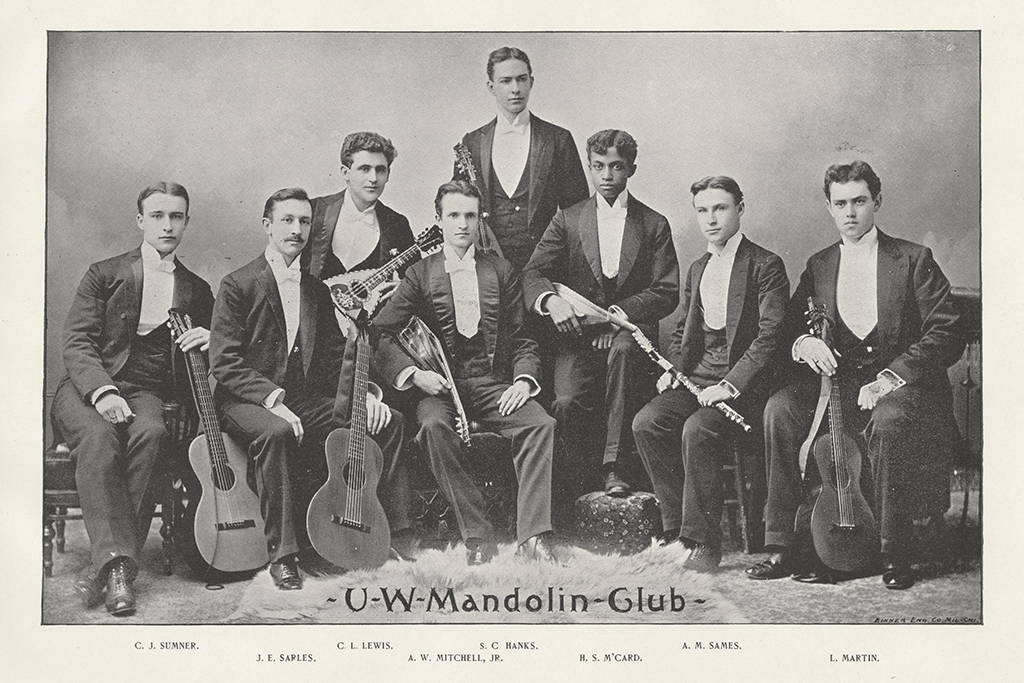

The 19th century Mandolin Club went on a rollicking, multi-city tour. UW Archives S15959

The UW Mandolin Club’s first gig involved one polka, two waltzes, 400 audience members, and a lot of snow in March 1893. The mandolin, banjo, and glee clubs soon joined forces for a rollicking, multicity concert tour. Perusing yearbooks gives you a glimpse of the action, but playing the group’s repertoire gives you a taste of the experience. Grab an instrument, find “Mendota Lake Waltzes” in the Wisconsin Sheet Music Database, and give it a whirl.

This sheet music collection is the Wisconsin Idea in musical form. If singing’s your thing, try its voice-and-piano odes to cities throughout the state. “Eau Claire Is There” and “I Went for a Walk in Oconomowoc” brim with vintage lingo and charm. So do “U-rah-rah Wis-con-sin” and other sing-alongs for sports fans of yore. The blue ribbon goes to “Wisconsin Sue,” which recalls a Badger football meet-cute: “When I heard you holler, I bet a half a dollar / On Wisconsin, On Wisconsin / Now I’d bet my life on you.”

A freshman beanie. UW Archives

Hats from Hell

Music was, for the most part, wholesome entertainment at the turn of the 20th century. A less wholesome pastime was tormenting newcomers. Many colleges mandated silly hats and harassment for first-year students. It’s hard to fathom, considering current efforts to curb hazing on campuses.

Starting in 1901, UW–Madison made male freshmen wear matching beanies from Varsity Welcome through Thanksgiving in the fall, and from Easter through Cap Night in the spring. Tossing these beanies into a bonfire was the highlight of Cap Night — and burning them signified freedom. If a freshman didn’t touch the beanie’s red button when talking to upperclassmen, he could expect to be thrown into the lake.

Preparing the Cap Night bonfire in 1921. UW Archives S09483

Punishments for other infractions ranged from embarrassing to dangerous. In 1923, so many bones were broken that the student court ended the cap requirement. UW Archives retains one of the few beanies that escaped the bonfire flames, plus photographic evidence of Cap Night’s wildness.

A Recipe for Success

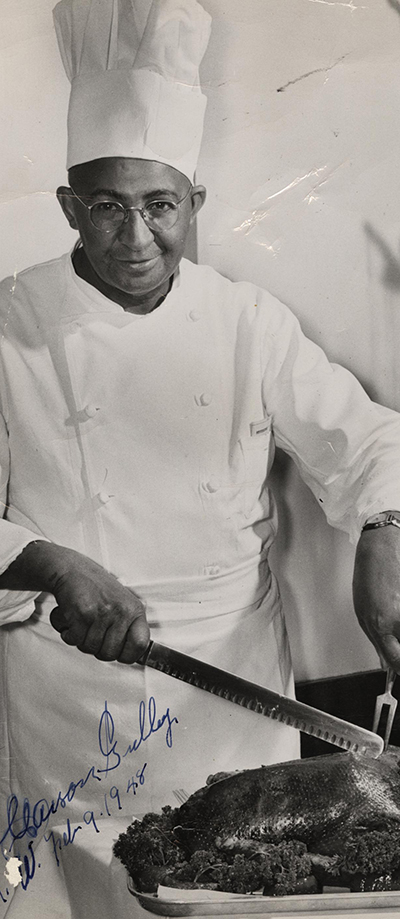

A chef hat was Carson Gulley’s go-to headwear. As the residence halls’ head chef from 1927 to 1954, he proved that dorm dining halls could rival fine-dining restaurants.

Gulley proved that dorm dining halls could rival fine-dining restaurants. UW Archives S17353

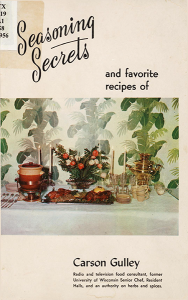

Gulley’s artistry attracted numerous fans, but it was just one ingredient in his success. His generous spirit and love of learning served him well as an author and a host of the Madison TV and radio programs What’s Cooking and Cooking School of the Air. One of the most delectable finds in UW Archives is 1956’s Seasoning Secrets and Favorite Recipes of Carson Gulley. It’s both a cookbook and an invitation to strive for greatness.

“The only equipment I brought to the work was an open mind and wide-open eyes,” Gulley explains in the preface. “I feel that anybody can be a creator in the art of cooking if he or she is willing to work open-mindedly to please, and to continue with constant experimentation.”

This “attitude is everything” sentiment infuses each page, whether Gulley’s describing a roasting method or his dishwashing job in an Arkansas oil town. He shares every trick for nailing his famous fudge-bottom pie, a campus staple to this day. There’s even a baked raccoon recipe, which will keep you reading even if you have no intention of preparing it. Gulley insists that you try the baked beans he spent years perfecting. “If properly prepared,” he writes, they “will win many friends.”

Both a cookbook and an invitation to strive for greatness. UW Archives

Though Gulley won many friends over the years — including inventor George Washington Carver, who encouraged him to write cookbooks — he couldn’t escape discrimination. It foiled many attempts to secure a home in Madison and a supervisory role at the university. As his shows and speaking engagements turned him into a celebrity, he used his clout to push for Madison’s first fair-housing ordinance. It passed in 1963, a year after his death.

Gulley’s quest for greatness lives on through the many people he helped and inspired, and through his words, which UW Archives continues to preserve and promote.

The Mood of 1970

In the beginning, Vietnam War protesters looked to civil rights leaders for tactics. Speeches and sit-ins were common. As the conflict wore on, the threat of violence increased, and the UW campus became a tinderbox. “It was obvious to me that something was going to happen,” James Huberty ’71, MS’74 remarked in a 2007 interview for UW Archives’ oral history program.

A scene of destruction following the Sterling Hall bombing. UW Archives

Foreboding turned to panic on August 24, 1970, when a bomb ripped through Sterling Hall. It missed its target, the Army Math Research Center, and killed physics researcher Robert Fassnacht MS’60, PhD’67.

Paul Ginsberg ’52 had just begun his 17-year tenure as dean of students. Seeing Chancellor Edwin Young and UW president Fred Harvey Harrington cry was deeply moving. The scene unfolded on Bascom Hill as they announced the tragic news to the campus community.

“Those tears were real,” Ginsberg told the oral history program in 1996.

Tear gas canisters from the antiwar protests. Katie Nash

When Huberty attended one of the fall’s first antiwar protests, he was shocked by the low turnout. A year earlier, thousands of students would have participated.

“No one wanted to be associated with that bombing where someone had died,” he said.

Huberty felt driven to document these confusing times. He collected posters, fliers, and newspapers that captured the mood of 1970.

He wasn’t the only one collecting. A student from the class of 1973 found two empty tear gas canisters in the wake of the bombing, then saved them for more than 50 years. The canisters reached UW Archives in 2023, through an anonymous donation.

The Conservation Kid

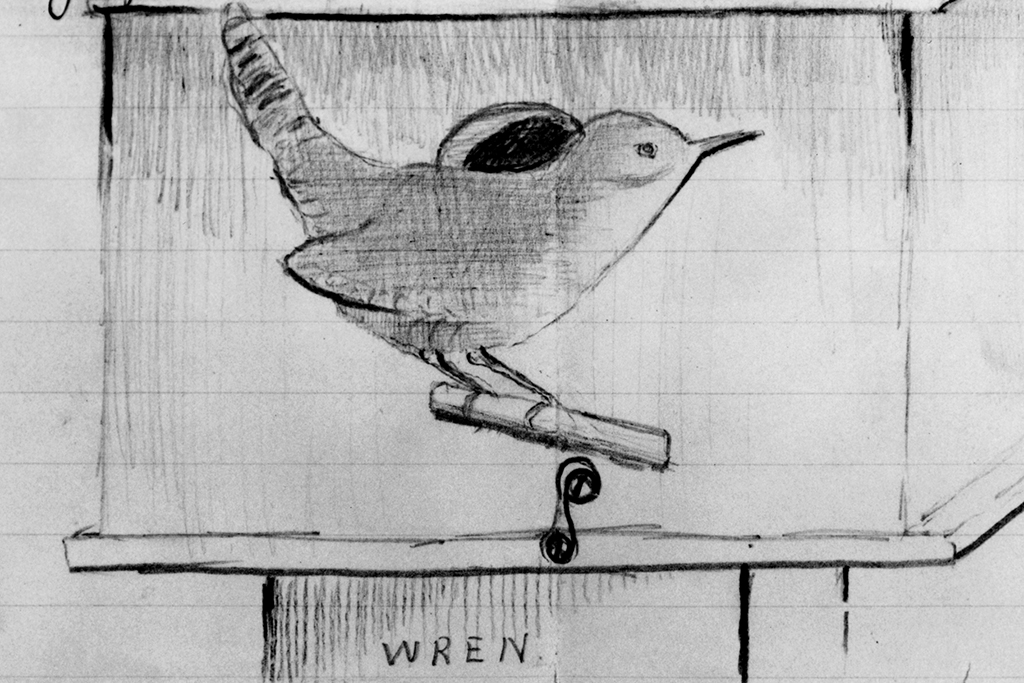

UW Archives has birdwatching journals and speeches by young Aldo Leopold (top left). UW Archives S01564 x25 1088

In addition to being an environmental visionary and the author of the conservation classic A Sand County Almanac, Aldo Leopold was UW–Madison’s first wildlife management professor and a key figure in the Arboretum’s growth. In other words, it’s no surprise to find his binoculars and hunting maps in UW Archives. What’s surprising is finding so much evidence of his youth.

The UW’s vast Aldo Leopold collection includes his birdwatching journals from 1903, the year he turned 16. Leopold named and numbered the species he observed, noted whether they were visitors or permanent residents, and classified them by order, family, and subfamily.

More than a dozen notebooks from Leopold’s high school days also reside in UW Archives. One contains a speech he wrote for a 1904 contest. It’s a chance to see some of his earliest thoughts on forest conservation, which he went on to study at Yale. Curious what Leopold learned in his college classes? Answers await in Archives. Wondering what his own lectures sounded like? The Archives might even have evidence of that.

A Leopold original from around 1900. UW Archives X25 2934

“I’ve been told that a recording of him speaking on public radio made it to UW Archives, but we don’t know if it survived,” says Nash. “If it turns up, that will be an incredible find.”

A Case for Cannabis

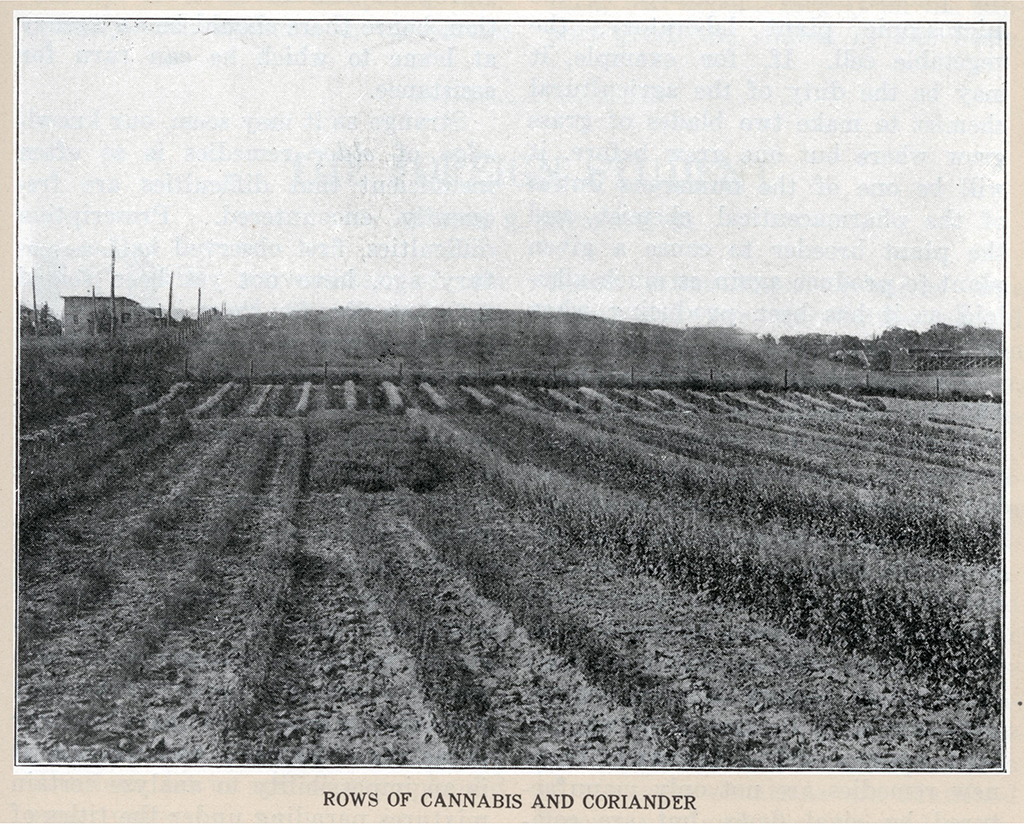

UW Archives’ collection of Wisconsin Alumni Magazine issues shows how UW–Madison became a research powerhouse. According to a December 1914 article, the university created “the first pharmaceutical research station in the United States.” Known as the Wisconsin Pharmaceutical Experiment Station, or Pharmaceutical Gardens, it grew medicinal plants for scientists to study and turn into medications.

The country’s first pharmaceutical research station grew medicinal plants for scientists to study and turn into medications. UW Archives S16649

“The eyes of the pharmacists all over the United States are upon Wisconsin,” wrote School of Pharmacy director Edward Kremers PhG 1886, BS 1888, who helmed the project from 1913 to 1933. In 1913, Pharmaceutical Gardens gained $2,500 — worth $77,000 today — in annual state funding. It also moved from the Camp Randall area to a slope near Picnic Point, growing rows of cannabis where Eagle Heights apartments now stand.

Legislators had few qualms about using state money to grow marijuana on university property. The 1913 bill establishing the station passed unanimously. It might not have done so a few years later, when public opinion shifted. By 1931, marijuana was illegal in 29 states, and Pharmaceutical Gardens came to an end in 1933.

The Wonders of Teejop

UW Archives tells the story of Charles E. Brown, the Wisconsin Historical Society’s first museum director, who devoted his career to preserving Native American history.

Brown (left) forged relationships with First Nations leaders like Chief Yellow Thunder. UW Archives 2017s00206

In a 1914 Wisconsin Alumni Magazine article, Brown highlighted Madison’s “remarkable” burial mounds, criticized the university’s reckless treatment of them, and urged readers to “realize their importance.” It was a bold move in an era marked by offensive practices, including a satirical peace-pipe ceremony outside the Historical Society headquarters.

Brown helped save hundreds of local mounds from destruction, including several from the ancient Ho-Chunk village of Teejop. He brought together “a wide and diverse group of citizens, from rural farmers to governors to Indigenous people, to contribute information about sites and artifacts, and to work alongside him for preservation,” according to a 2022 blog post by Wisconsin Archaeological Society president Robert Nurre.

Forging relationships with First Nations leaders was an important part of Brown’s process. He did this through events such as the Blackhawk Centennial gathering, where he socialized with Ho-Chunk chiefs, and ongoing correspondence with Potawatomi chief Simon Kahquados.

Brown loved to learn about tribal legends from First Nations leaders. UW Archives

Tribal legends were one of Brown’s favorite things to learn from these chiefs, and Muir Knoll was one of his favorite campus places to share them. He did this at “Folk Lore” presentations in the 1910s and through pamphlets for UW–Madison’s summer-school students. Material from his 1927 pamphlet “Lake Mendota Indian Legends” abounds on local websites nearly a century later. One of the most striking legends concerns avian deities on Lake Mendota’s north shore: “Lightning is caused by the flashing of their eyes and peals of thunder by the flapping of their wings.”

Brown also produced booklets to help students savor campus. Several live in UW Archives, and a larger collection resides at the Wisconsin Historical Society. One specimen, 1930’s “The Birds of the Campus,” teems with pioneers’ bird superstitions. According to Brown, peacock feathers were thought to bring calamity, while yellow-bird sightings meant “gold in your sock.”

These days, Brown’s legacy shapes Our Shared Future, UW–Madison’s collaboration with the Ho-Chunk Nation. The project uses Brown’s writings to show what Teejop was like and help Badgers envision a more just and peaceful future.

A Sign of the Times

Long before the Stonewall riots, UW–Madison’s LGBTQ+ communities gathered for cocktails and conversation at the 602 Club. Located at the corner of Frances and University, this bar opened its doors to gay men and lesbians starting in the 1950s.

The 602 Club welcomed gay men and lesbians starting in the 1950s. UW Archives, 602 Club collection, Accession 2017/122

Owner Dudley Howe was a “tolerant sort who welcomed all patrons as long as they weren’t bothering anyone else,” according to Scott Seyforth PhD’14, who cofounded the Madison LGBTQ+ Archive that UW Archives maintains. Seyforth says the 602 Club wasn’t officially a gay bar but was “informally arranged for gay men in the front half of the bar, straight patrons in the back half.”

This collection includes slice-of-life photos by John Riggs ’70, a 602 Club bartender who brought his camera to work. The images drew Andy Soth MS’09 to the collection when producing Wisconsin Pride, a 2023 PBS documentary.

“These are some of the era’s only photographs of gay men socializing,” Soth says.

Today, the 602 Club sign glows above UW Archives’ information desk, welcoming visitors from all walks of life. UW Archives

Today, the 602 Club sign glows above UW Archives’ information desk, welcoming visitors from all walks of life and reminding them that their stories matter.

How to Speak “American”

Audio recordings add fascinating dimensions to some UW stories. To see how, listen to those for the Dictionary of American Regional English (DARE) in the UW Digital Collections.

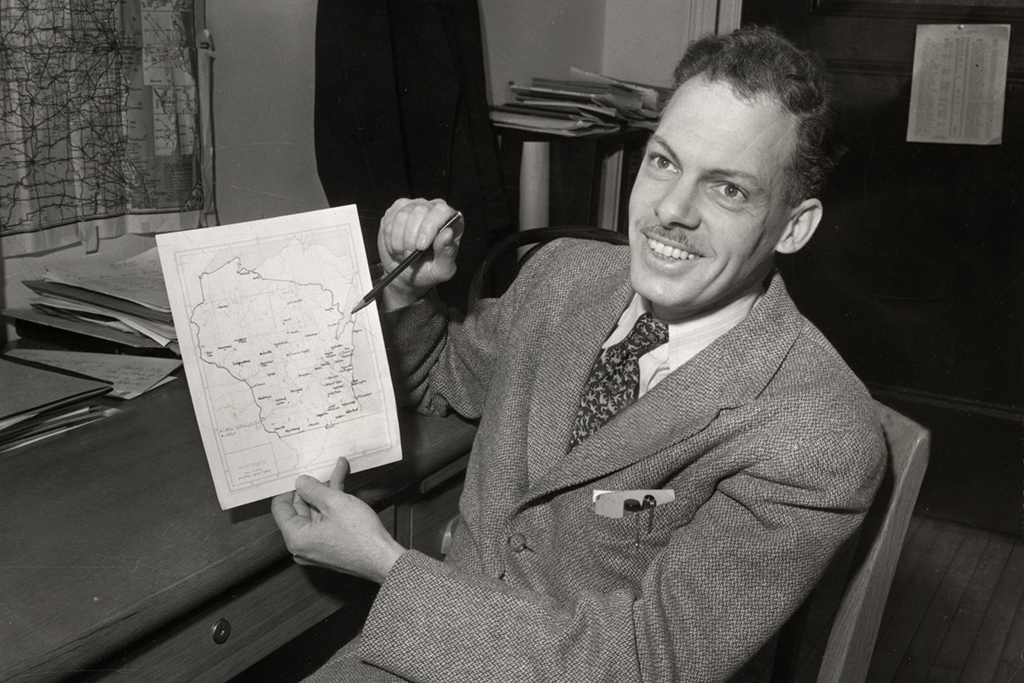

Frederic Cassidy, founder of the Dictionary of American Regional English, with a map of Wisconsin. UW Archives S09026

Between 1965 and 1970, this UW-led project dispatched fieldworkers to interview 3,000 people in more than 1,000 American communities, documenting pronunciation variations and lesser-known turns of phrase. All participants did a read-aloud of “Arthur the Rat,” a story designed to tease out these differences, and many told tales from their day-to-day lives.

The DARE Newsletter provided updates on the UW-led project that documented pronunciation variations and lesser-known turns of phrase. UW Archives, Series 7/10/22/00/1

Look closely and you’ll find famous alumni in these recordings. One is filmmaker Terry Zwigoff ’70 (Crumb, Ghost World), whose fieldwork took him to Illinois and Tennessee. Awkward yet lovable, Zwigoff’s chats are a treat, but the interviewees are the real stars. Defunct dialects are well represented, as is slang that deserves a wider audience. Tired of someone’s nonsense? Call out their flummadiddle. Think they’re extraordinary? Tell them they’re a whoopensocker. It’s just the word I’d choose for UW Archives. •

Jessica Steinhoff ’01 is a Madison-based author and campus-history nerd.

Published in the Winter 2023 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.