So You Think You Know Ron Dayne?

“I would get 38 carries like it was nothing,” says Dayne, who won college football’s highest honor, the Heisman Trophy, 20 years ago.

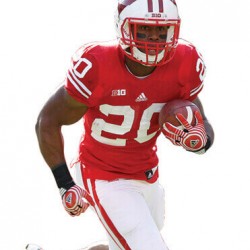

I was sure I knew a lot about Ron Dayne ’17, even though I had never actually watched him play. After all, he’s Ron Dayne. Growing up in Wisconsin, I heard stories of his Badger football dominance. When I attended games as a student in 2010 — more than a decade after his playing days at Camp Randall — the crowd still reserved its biggest roar for the Great Dayne’s highlights at the climax of the pregame montage. His legend was that of a wrecking-ball back who, at some 270 pounds, ran through defenders on his way to an NCAA rushing record, consecutive Rose Bowl wins and MVP honors, and the 1999 Heisman Trophy.

Dayne set me straight during an interview this summer, describing his approach as a “little back trying to be pretty,” despite appearances to the contrary. “Everybody would say, ‘You like running people over.’ I was like, ‘I’d rather just run around them.’ I was fast for my size,” he says.

I expected a larger-than-life presence, but Dayne, 41, is naturally reserved and stoic. He rarely cracks a smile or modulates his voice, and barely makes eye contact. That affect dates back to his playing days and may have been something of a survival mechanism during his childhood. His parents divorced when he was in elementary school, after which his father was absent and his mother fell into a cycle of drug abuse. “It made me grow up,” Dayne says. “I had to raise my sister. I had to be like a parent at 10 or 11.”

He couldn’t play football — his one true passion — until high school because of weight limits. Then he immediately made his mark on the sport as a star running back for Overbrook High School in New Jersey. Most colleges envisioned him as a blocking fullback, and Notre Dame even recruited him as a defensive tackle. In 1995, Wisconsin was one of two programs to promise him an opportunity as a feature halfback. “[Coach Barry Alvarez] knew something. He felt something,” Dayne says. “He came to my house and gave me a big hug when he walked in the door. He’s like, ‘Ronnie!’ I was like, ‘Okay!’ ” It was the start of a four-year streak that revived Wisconsin football and established the beefy, run-first brand it maintains to this day.

“We didn’t throw the ball,” Dayne says. “I would get 38 carries like it was nothing. We’d run the same plays, and everybody knew what we were running. [The defense] would say, ‘They’re coming right here.’ Our linemen would say, ‘Yep, we’re coming right here. And we’re going right there [to the endzone].’ Touchdown.”

His most memorable run was one for the record books, coming in his final home game on November 13, 1999, a victory that clinched a Rose Bowl appearance. With 80,000 white “Dayne 33” towels waving above him, he busted through the middle of Iowa’s line and froze a linebacker with a sidestep. “I saw his face — he didn’t want to tackle me anyway,” Dayne says. With another quick shift, he evaded a defensive back and rumbled down the sideline, gaining 31 yards and breaking Ricky Williams’s all-time rushing record from the year prior. His 7,125 career rushing yards, counting postseason games, are still the most in NCAA history.

Dayne’s record-breaking success in college didn’t carry over to the NFL. He was drafted in the first round by the New York Giants, who already had a lead back in Tiki Barber and employed a different blocking scheme. Although Dayne’s size was an asset at Wisconsin, it was labeled a liability in the NFL and became a source of derision for fans. Media documented his weight obsessively. To impress scouts, he lost nearly 20 pounds heading into his rookie season, which he believes ultimately hurt his performance. “You could feel the difference when you’re getting hit, and I was still the same speed,” he says. By 2003, he had gone from being the most prolific college player in the country to being benched for an entire season in the pros. He retired in 2007 after stints with the Denver Broncos and Houston Texans.

Dayne has devoted much of his time since to his kids. “I wanted to be around, [because] my parents never were,” he says. He raised his oldest, Jada, while he was in college, and now she plays soccer at the University of Michigan. Javian is a running back for Boston College, and Zion is being recruited by Ivy League schools as a defensive lineman.

Dayne still lives in the Madison area and is involved in a number of charitable efforts for children. His legend lives on here, too. A couple years ago, he returned to the UW to finish his Afro-American studies degree. Some of his classmates had yet to be born when he played at the UW. But they knew Ron Dayne, and they couldn’t keep from showing it.

“[The students] acted like they didn’t know me until it was the end of class,” Dayne says. “And when the class is done, there’s a line outside: ‘Mr. Dayne, can you sign this for me?’ They played it cool all the way until the end.”

Published in the Fall 2019 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.