Serious Business

A researcher splits and redistributes cells at the Influenza Research Institute at UW-Madison. Photo: Jeff Miller.

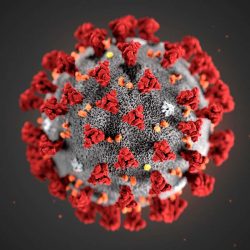

As flu season begins, UW researchers work to stay a step ahead.

For public health officials, few things are more worrisome than the prospect of an avian influenza pandemic.

As the winter flu season begins in earnest, the strain of greatest concern to researchers and those who track the disease is H7N9, which emerged in China in April, infecting at least one hundred and thirty people and killing forty-four. Those infected, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control’s working hypothesis, most likely became sick after being in close contact with infected poultry or contaminated environments, as the virus has no recognized ability to transmit between people.

But bird flu is an opportunistic organism. When it infects humans and other animals, it can blend with seasonal flu viruses or otherwise mutate to adapt and jump from one host species to another. Thus, the possibility of H7N9 becoming a human pathogen and sparking a global outbreak of influenza is to be taken with the utmost seriousness, explains Yoshihiro Kawaoka, a UW professor of pathobiological sciences.

“We need to know whether the virus has the capacity to adapt fully to humans so that it could become as transmissible as seasonal influenza,” says Kawaoka, a world-renowned expert on influenza.

Kawaoka has proposed studies to identify genetic mutations that could enable the H7N9 virus to make the jump from birds to mammals. “These studies will enable us to assess how many mutations are necessary for these viruses to become transmissible in mammals, and give us a sense of their pandemic potential,” he says.

If the studies are approved by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, they will be conducted in UW–Madison’s Influenza Research Institute, a state-of-the-art, high-containment facility designed expressly for such work.

Knowing the mutations required by the virus to make the jump from birds to mammals arms the global flu surveillance network, giving public health workers some idea of the mutations to look out for in naturally circulating viruses. That information, says Kawaoka, can buy precious time to assess and plan the strategic deployment of life-saving countermeasures.

The work also informs efforts to develop a vaccine for the virus and devise other tactics. This may be especially important for H7N9; research published by Kawaoka’s group earlier this year showed that the virus is quick to circumvent the few antiviral drugs available to treat patients who become infected.

“The virus readily acquires antiviral resistance in individuals treated with these drugs,” Kawaoka notes.

His group is already at work developing a candidate virus that could be used to help develop a new vaccine against H7N9.

Published in the Winter 2013 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.