Rethinking the American Museum

Marcela Guerrero MA’05, PhD’15 is breaking barriers as the Whitney’s first curator of Latino art.

Marcela Guerrero MA’05, PhD’15 is lucky. She sees her role model every morning. When Guerrero, a senior curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City, steps off the elevator to go to her office, right in front of her hangs a huge, stunning 1916 painting of the museum’s founder, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney.

The steady gaze of the confident, relaxed benefactor greets everyone, but Guerrero, 43, takes away a special message. “It’s a reminder that the intention of the woman who built this space was to give artists opportunity, visibility,” she says. “We’ve come a long way since the early 20th century, but we can still make art more accessible to more people.”

Guerrero is one of the nation’s few Latina curators. Latinos make up only 3 percent of museum leaders, curators, and educators, according to a 2015 Mellon Foundation study. Today, museums are rethinking the cultural canon, and in her groundbreaking role at the Whitney, Guerrero, who was born and raised in Puerto Rico, ranks as the first curator to specialize in acquiring and showing works by Latino artists.

“She’s the right person at the right time in a critical moment of American art history,” says Mari Carmen Ramírez, who in 2001 was the first curator of Latin American art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. “She’s made it her life’s mission to give voice to this very heterogeneous community.”

Anguished, Jubilant, Beautiful

Whitney Museum director Scott Rothkopf describes Guerrero as “a real visionary.” Together they are formidable allies.

“We are revamping the museum’s identity and being more forthright about aspects of our collection we’ve neglected and aspects of the American identity that haven’t been shown or recognized,” Guerrero says.

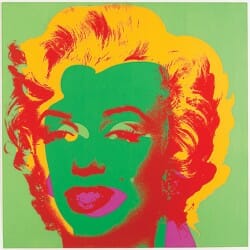

Her multiartist exhibition no existe un mundo poshuracán: Puerto Rican Art in the Wake of Hurricane Maria marked the first time a major U.S. museum had celebrated the island’s art in 50 years. It showcased works by 20 artists living there and in the diaspora, including Frances Gallardo, Elle Pérez, and Gamaliel Rodríguez. Spanning the Whitney’s sixth floor, the show won raves as one of 2022’s best. ARTnews magazine called it one of the year’s 25 “defining” exhibitions. The New Yorker hailed it as “anguished, jubilant, galvanizing, and often beautiful.”

Five years in the making, the event reflected Guerrero’s wrenching experience during 2017’s Category 5 hurricane, which killed nearly 3,000 people on the island. Hired five months earlier as an assistant curator, she was caring for her newborn daughter in her Brooklyn home when the storm hit. Her father, a retired pharmacy professor at the University of Puerto Rico, was trapped in Puerto Rico.

“My mom was here helping me, but he was incommunicado for three days,” Guerrero recalls. “We were desperate and concerned for his safety.”

Months later, when she returned home, the lingering devastation shocked her. “Things were already bad before Maria, but to see traffic lights not working symbolized no order,” she says. “It felt like the island was in a freefall.”

During the storm, Guerrero racked her brain about how she could help people back home. Soon the notion of doing a show, one she says was the most personal she may ever do, began to take shape. The resulting exhibition blended Maria’s psychological and physical traumas. Its sections highlighted not only the shattered infrastructure but also the ecological ruin, grief, and crushed tourism industry.

Guerrero knew that most museumgoers from the mainland had only a basic understanding of Puerto Rico. “People go there for a trip to the beach, but what else is happening there? There are people living, thriving, making life, surviving,” she says. “I wanted to provide that window into how people there live and make art.”

The event helped Guerrero crystallize her conflicted feelings about the status of Puerto Rico and its residents. When she speaks of the island, she always calls it a colony, never a territory, a term she says most Puerto Ricans think is a euphemism.

“The people of Puerto Rico do not have the same rights as other citizens,” she says. “It’s important to use that word — colony — because it’s a reminder that the U.S. was an empire whose colonialist project began when it colonized Puerto Rico in 1898.”

“The Realities Outside Our Walls”

Being a curator means more than developing new shows in collaboration with artists and Whitney staffers. Guerrero is also tasked with the equally daunting responsibility of acquiring works by Latino artists, either by purchasing pieces from galleries or by working with donors.

“That could be its own full-time job,” she says. “I sometimes feel guilty, because if I’m busy working on an exhibition, then that’s less energy I have to put into advancing our collection.”

Major gaps exist in the Whitney’s collection of Latino artists, and Guerrero has been up to the job. Thanks to her, nearly 25 percent of the museum’s 2021 acquisitions were works by Latino artists, including Firelei Báez, Dalton Gata, and Rodrigo Valenzuela.

Even seemingly mundane aspects of presenting art at the Whitney have been transformed by Guerrero. When she started, she noticed that the wall labels were only in English, though audio narrations were available in Spanish.

“It was shocking that labels were not also in Spanish,” she says. “It’s pervasive in other U.S. museums. It’s provincial, thinking that English is a hegemonic language.”

“We’ve come a long way since the early 20th century,” says Guerrero, “but we can still make art more accessible to more people.”

Today, the Whitney is starting to label works in both languages. “It’s about fair representation,” says Guerrero, who notes that Spanish is the second most spoken language in the U.S. “I always think about language justice and how in U.S. history sometimes families decided not to speak Spanish. They thought you had to assimilate, and to assimilate you had to shun part of your identity. So, how do we repair that in a public institution? I think it’s through better mirroring the realities outside our walls.”

Building trust with museumgoers is another challenge, one that she says is the most difficult part of her work. New York City has the largest Puerto Rican population outside of the island, yet such visitors are underrepresented at the Whitney.

“Mainstream museums have turned their back on this audience,” says Guerrero. “I hear it all the time, like, ‘Why would I go there? It doesn’t care about people like me.’ ”

To combat the problem, during the run of no existe, the museum established a partnership with the Center for Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College. Guerrero, along with Cris Scorza, the Whitney’s chair of education, is also building a network with other groups to create a cultural comfort level with community members.

On a clear day, when Guerrero looks out the windows of the curatorial offices, she can see the Statue of Liberty. She loves the view and is always drawn to horizon lines where she can see water. “That’s probably from growing up on an island, to feel a sense of home,” she says. “Tranquility.”

Imagining a New Future

As a child, Guerrero never dreamed of being an art museum curator. Neither of her parents was an artist, but they exposed her to the arts — and as an 18-year-old visiting Washington, DC, she found herself drawn to the Smithsonian’s art museums. Walking into those vast galleries on the National Mall reminded her of visiting churches.

“You’re immediately engaged in an exercise of interpretation, surrounded by beauty, by aesthetics, free to reflect,” she says. “You create your own experience with the art. No one’s telling you what to think.”

As an undergraduate, Guerrero majored in history of the Americas and art history at the University of Puerto Rico. Slowly, she began to realize she had the skill of communing with art.

“There are no words. You ‘read’ a work and ask yourself, ‘What does this communicate to me?’ ”

She began to see museums as dynamic places that brought out the best in her, and she sensed she would enjoy collaborating with others to share art with the public.

When Guerrero came to the UW for her master’s degree in art history, her life changed, thanks to her adviser, Professor Jill Casid. “Jill revolutionized how my brain operated,” says Guerrero. “She taught me to think critically and question everything.”

Twenty years later, the two remain friends, and Casid traveled to New York for the opening of the Puerto Rico show. She considered it a profound shift for artists who haven’t been getting the representation they deserve.

Does she think her former student is a rising star in the world of art museum curators?

“She was a rising star,” says Casid. “Now that star has risen.” •

Freelance writer George Spencer is a former executive editor of the Dartmouth Alumni Magazine.

Published in the Spring 2024 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.