Poetry of the Moment

In timely new collections, married UW professors Cherene Sherrard and Amaud Jamaul Johnson explore Black identity and struggle.

… I’m ashamed

of how much compassion I’ve shown our declared

enemies, which is what I was given, always unzipping

my jacket, attempting to speak before spoken to,

being pleasant, thinking everyone is watching.

And what they are waiting for is whatever I’ve placed

in my hand, which rarely feels like grace.

— “How often I’ve turned to Latasha Harlins, who would have been 43 this July,” Imperial Liquor

Even before the police brutality and Black Lives Matter protests earlier this year, Latasha Harlins was never far from Amaud Jamaul Johnson’s mind.

In 1991, Harlins walked into a Los Angeles convenience store and was shot in the back of the head by the store’s owner, who accused her of trying to steal a bottle of orange juice. She was Black. She was 15. She died with money in hand.

Johnson, a nationally renowned poet and English professor at UW–Madison, dedicated a poem to Harlins in Imperial Liquor, his new collection on race and fatherhood. A Compton, California, native, he left for college as his city burned following the acquittal of police officers who had beaten Rodney King around the time of Harlins’s death.

“One of the great anxieties I have is that it seems like these riots mark generational shifts,” Johnson says. “When my father was a teenager, he experienced the Watts riots in ’65. When I was a teenager in Los Angeles, there was a riot. And now my sons have rioting and protest that’s part of their adolescent experience. It feels like we’re caught in a dangerous loop.”

Such brutal realities of being Black in America — from slavery to today — underpin much of Johnson’s award-winning writings, as well as his wife’s. Cherene Sherrard, a fellow distinguished poet and professor in the Department of English, also released a collection this year. In Grimoire, she writes of the turbulences of Black motherhood that echo across generations.

Hear Johnson and Sherrard read and discuss their poetry in a presentation from the Wisconsin Foundation and Alumni Association.

In the couple’s poetry, the elegance of each line guides you deeper into a haunting scene. You agonize over pain and loss, violence and survival. You explore the transience of home, identity, and memory. And you start to understand why — as the country confronts racial strife and a devastating pandemic with precious little empathy — a poet’s touch is essential.

“During a time like this, when people feel like they don’t quite understand where things are going, where there’s a confusion or hopelessness, there’s a great call for poetry,” Johnson says. “We saw this after September 11. Poets deal in uncertainty — or what John Keats called negative capability. A poet exists in a space where the answers aren’t readily available, where you linger in a silence and speak into it.”

I packed the dishes in saddlebags between

copies of The North Star,

what issues we had not passed clandestinely on to other subscribers.

All items in the pastry shop were sold or returned to lenders, save

these blue-and-white cups and saucers in which I served custard or tea. …

Their mismatched sturdiness lent an elegance, a charm that led ladies

to linger over their little cakes. When we unpack in Michigan, all the cups

have chipped, all the saucers have fissures, but I use them anyway.

A reminder of what cannot be broken.

— “Chaney,” Grimoire

“Dreaming Historically”

Sherrard was a year into her PhD program in African American literature at Cornell University when Johnson arrived to pursue a professional master’s in African American studies. They met at an orientation event.

At the time, they didn’t know poetry was in their future. But their academic training and dedication to African American history have led to a distinctive body of work that gives new voice to historical figures.

Johnson calls this process “dreaming historically” — immersing oneself in a moment of time and suspending knowledge of what comes next. Textbooks lay out the facts of history; their poetry transports you to the scene. Imagining history through sight and sound, by touch and taste, allows for deeper truths to emerge.

Johnson calls this process “dreaming historically” — immersing oneself in a moment of time and suspending knowledge of what comes next. Textbooks lay out the facts of history; their poetry transports you to the scene. Imagining history through sight and sound, by touch and taste, allows for deeper truths to emerge.

Johnson released Red Summer, his 2006 debut collection, after completing the prestigious Wallace Stegner Fellowship at Stanford University. The title, referring to the 1919 race riots and lynchings that erupted across the country, feels as urgent today as at the time of publication. With lyricism inspired by the blues, the collection explores the nature and permanence of violence. In “Chicago Citizen Testifies in His Defense,” Johnson writes of the murder of Eugene Williams, a Black teenager who drowned during the Red Summer when his raft floated toward a segregated section of beach and a white man pelted him with rocks: “The fate of the rock, like that of the boy, / falls somewhere between gravity and god.”

In 2013, Johnson released Darktown Follies, shifting from tragic violence to tragic humor. The collection reopens the curtains to vaudeville and minstrel shows, in which blackface became a staple. As with all of his writing, the historical bleeds into the contemporary. In the book’s first poems, he portrays Black performers who negotiated degrading acts to secure a place on stage; later, he touches on appropriation, stereotype, and performance in our lives today. The uncomfortable humor is only fitting for the historical subject.

In 2013, Johnson released Darktown Follies, shifting from tragic violence to tragic humor. The collection reopens the curtains to vaudeville and minstrel shows, in which blackface became a staple. As with all of his writing, the historical bleeds into the contemporary. In the book’s first poems, he portrays Black performers who negotiated degrading acts to secure a place on stage; later, he touches on appropriation, stereotype, and performance in our lives today. The uncomfortable humor is only fitting for the historical subject.

“There’s something about doing historical work, when you’re trying to humanize people in the past to understand both their strengths and weaknesses, that hopefully allows us to be kinder to each other,” Johnson says.

At times, the process of dreaming historically involves a physical element. For Grimoire — meaning a book of magic spells — Sherrard drew inspiration from the smells and tastes of her kitchen. To better understand Malinda Russell, the first African American to publish a cookbook, Sherrard re-created her 19th-century recipes as authentically as possible.

Little is known about Russell, a free Black woman and single mother from Tennessee who moved to Michigan and published A Domestic Cook Book in 1866. But Sherrard brilliantly folds her recipes into the first part of the collection. In “Marble Cake,” she writes: “My son, ½ cup white flour, ¼ cup brown sugar / has trouble with fractions. When pregnant / I did not follow instructions, beat the yolks and sugar / together until very light … Mixed children usually / come out beautifully. The doctor is unsure about mine. / Paper and butter the pan, first a layer of the white, / then of the dark, alternately finishing with the white.”

That poem’s narrator is a contemporary Black mother and amateur cook whom Sherrard created to interact with Russell across time. The enduring hardships of Black motherhood tie Grimoire together, with later sections exploring grim disparities in childbearing and childrearing. The book notes that Black infants are twice as likely to die as white infants, an inequity more severe today than at the time of Russell’s cooking.

In “Outcome,” such statistical prophecy dooms all Black mothers: “Her serve is 125 miles an hour / but she cannot outrun this. / She has won, has published, / but she cannot outwrite this. / She has starred, has danced, / but she cannot out-twirl this.”

While reading Russell’s cookbook, Sherrard was drawn to the use of “receipt,” an archaic form of “recipe.” The word’s versatility — used for spells, food, and medicine, or, more imaginatively, to refer to the steps of successful parenting — allowed for a potent mix of themes.

Rereading her collection now, she’s finding the poems “eerily prescient” as she raises two teenage sons during a time of racial strife and pandemic.

“On one hand, you want to protect a space for joy, for well-being, for growth, for experience, for the kind of trial and error that’s really necessary to develop independence,” Sherrard says. “And yet, you’re always weighing that against the fact that they don’t have as much room to make mistakes as other children.”

Over the summer, as protests over police violence consumed the country, Sherrard and Johnson weighed how to discuss the cultural moment with their sons, fearing how much they’ve already internalized the tragedies of Trayvon Martin, Tamir Rice, and others. The family took a trip to State Street in downtown Madison, where local artists had transformed broken windows into vibrant plywood murals honoring victims of police violence and conveying hopeful messages of unity and change.

“We wanted them to see images of affirmation — celebrating Black life — so that it’s not one long doom scroll of Black death,” Sherrard says. “Seeing those images was a really good example of how art can bring an awareness and understanding of the struggles people are having.”

the most dangerous men

in my neighborhood

only listened to love songs

to reach those notes

a musicologist told me

a man essentially cuts

his own throat. some nights

even now, i’ll hear a falsetto

and think i should run

— “Smokey,” Imperial Liquor

Tragedy Baked In

For all its historical references, Imperial Liquor is perhaps Johnson’s most personal and vulnerable work, part ode to the Compton of his youth and part nod to the anguishing parent everywhere. It contains his signatures: stunning lyricism and evocative imagery.

Released in February, the collection became revelatory just a few months later with the police killing of George Floyd. Johnson captures the urgency of the Black Lives Matter movement, with one reader posting on Goodreads: “If there is a book for this moment, this is it.”

In the poem dedicated to Harlins, Johnson writes: “My sons / were gone too long. They are developing this habit / of walking their allowance down to our corner store. / One of the many ways I’ve failed them, we haven’t / had that talk about their bodies, about the alarming rate / of illiteracy surrounding their bodies.”

And in “Don’t Forget You(r) Lunch,” the narrator addresses his son directly. No matter how friendly, honest, successful, or polite he grows up to be, it may never be enough: “the first time a police officer / put a gun to my head, the night / was as still and musty and oily / as your body is now.”

Johnson reads everything aloud as he writes. “The music has to be right,” he says. He believes poetry has both a sound system and an image system, and rather than rhyme words, he might correlate strong images, like fire and blood. As a child, he first fell in love with language because of hip-hop and R&B.

“Tough guys in my neighborhood didn’t necessarily listen to gangster rap. They listened to love songs,” he says. “So there’s this relationship I have to sound, that a really beautiful thing often has this tragedy baked into it — like, what does it mean to be afraid of a lullaby?”

Johnson is soft-spoken, in contrast to the fierce, baleful language of his poetry. Even in casual conversation, he speaks in a series of ellipses and questions, one thought inevitably interrupted by a deeper one. Such deliberation and doubt serve a poet well.

“Poetry isn’t about answering questions, necessarily,” Johnson told Boxcar Poetry Review. “But maybe, after several poems, we’ll begin to ask better questions, or get somewhere closer to the truth.”

Johnson: “A poet exists in a space where the answers aren’t readily available, where you linger in a silence and speak into it.”

In Sherrard’s writings, amid deep explorations of race and gender, her personality shines through with unexpected moments of levity. Sharp satire and pop-culture references permeate her work. In Grimoire, “ginger” is as likely to refer to the cooking ingredient as it is the Gilligan’s Island character. “In my episode,” Sherrard writes, “Ginger marries the Professor / after pushing that insipid Mary Ann / out to sea on a bamboo raft.”

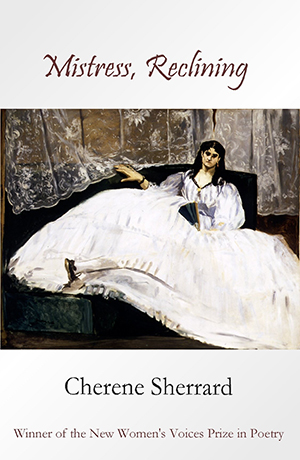

Sherrard arrived on the poetry scene in 2010 with Mistress, Reclining, a chapbook that won the New Women’s Voices Prize in Poetry. She earned praise for crafting an intricate persona for Jeanne Duval, the multiracial mistress of 19th-century poet Charles Baudelaire. In 2017, she published Vixen, a dramatic collection filled with explorations of identity and a historical narrative on slavery with avatar Annabelle X.

Sherrard credits her ability to develop fictional and historical personas to her upbringing as an only child. “I grew up with my own imagination and books as companions,” she says. “That sense of transforming into another person was very appealing to me.”

Raised in Los Angeles, she was initially drawn to film and became active in theater. “At some point,” she told Water-Stone Review last year, “I started writing my own characters instead of pretending to be someone else’s.” Her bold approach has earned her an admiring label from the Washington Independent Review of Books: “a writer who doesn’t subordinate herself to make a poem.”

A flood, like Noah’s flood,

like after Katrina, like the

Mississippi’s goddamn muddy

Blues, like Sylvia on death,

or Toni on slavery, like swag

surfing over the breakwater,

the levees levitating,

water seeping up through

cracked foundations, like molasses,

drowning cows in a pasture

of sweet. This placental blood

is an abrupt surprise.

— “Dixie Moonlight,” Grimoire

Living with a Poet

For Johnson and Sherrard, poetry is often superseded by the demands of parenthood and professorship. Writing time feels like stolen time.

“A lot of the work is just trying to block out other responsibilities to get the writing done, and I’m always surprised that it happens,” Johnson says. “I think, ‘Where did that poem come from? How is that possible?’ It feels like a gift when a poem really comes together.”

Sherrard is a fellow at the UW–Madison Institute for Research in the Humanities and teaches 19th- and 20th-century literature courses, including one this spring on novelist Toni Morrison. Johnson is the director of the MFA program in creative writing and leads poetry seminars. Time is so precious that they rarely discuss or share their poetry while it’s in progress, afraid to burden the other.

“We used to do more of that,” Sherrard says. “Now it’s more like, ‘I wrote this poem, look!’ And he says, ‘Good for you!’ … As important as poetry is, it’s also the debris of the lived experience. It’s the thing that we’re constantly shedding so we can kind of move on to something else.”

And as they grapple with their own work, they’re training the next generation of great writers and thinkers.

Before her fellowship, Sherrard was the director of graduate studies for the English department, where she oversaw the Bridge Program that allows students who finish their master’s degree in Afro-American studies to transfer to the English program and earn an accelerated doctorate. She notes that the program has increased the number of Black students earning PhDs from the UW.

Johnson has seen his creative writing students go on to make major literary contributions. Most notable is Danez Smith ’12, a queer Black poet whose collection Don’t Call Us Dead was a finalist for the 2017 National Book Award.

“As a teacher, it’s a real honor to see what’s possible in a poem,” Johnson says. “I don’t care how rough a draft is — I always think there’s something there.”

Even as self-proclaimed homebodies, Johnson and Sherrard have found releasing poetry collections during a pandemic to feel particularly isolating. Johnson was set to embark on his book tour the same week the country shut down in March. Beyond the impact on publicity and sales, sharing the work through virtual readings doesn’t allow for the usual hallway chats with readers or dinner with contemporaries. “I remember a colleague saying, ‘A poet really touches every book that they sell.’ There’s kind of an intimacy to it in terms of that exchange,” Johnson says.

“I’ve had to adjust my expectations around what I would be doing to shepherd this new book into the world,” Sherrard adds, noting that the altered process has involved “a little bit of mourning.”

Fortunately, these poets know how to support each other.

“Living with a poet makes this work feel really normal,” Johnson says. “We both respect the energy and effort that go into creating art. I imagine some people may think, ‘Oh, it seems so interesting or unusual to write poetry.’ But poetry is kind of a family business. It’s just who we are.” •

Preston Schmitt ’14 is a staff writer for On Wisconsin. "Smokey" and "How often I've turned to Latasha Harlins, who would have been 43 this July" from Imperial Liquor by Amaud Jamaul Johnson, copyright 2020. Reprinted by permission of the University of Pittsburgh Press.

Published in the Winter 2020 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.