Our Man in Berlin

As an American journalist in Germany, Louis Lochner told the story of the rise and fall of the Third Reich.

Louis Lochner 1909 was dumbfounded when British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain returned to London and trumpeted “peace for our time” after signing a pact in Munich that allowed Germany to annex the Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia. The mood outside 10 Downing Street on September 30, 1938, was euphoric, and Chamberlain recommended that the assembled crowd “go home and sleep quietly in your beds.”

Lochner, the bureau chief for the Associated Press in Berlin, couldn’t understand the naïveté behind appeasement — he knew better than anyone that Adolf Hitler would not stop until he dominated all of Europe. That night, as Britain slept, the Nazis marched into Czechoslovakia.

Six weeks later, Lochner filed this story for the AP:

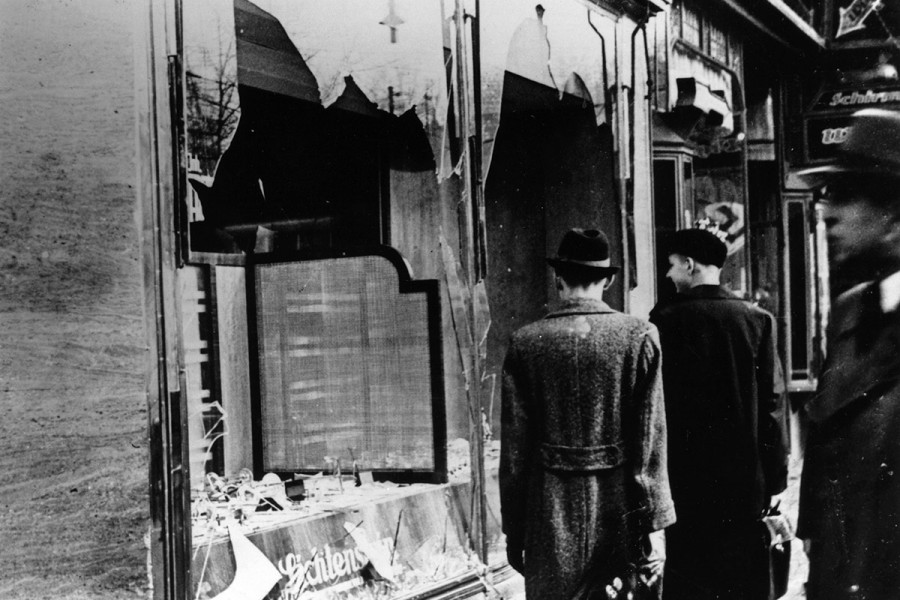

Berlin, Nov. 10 — The greatest wave of anti-Jewish violence since Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933 swept Nazi Germany today and Jews were threatened with new official measures against them.

Millions of dollars worth of Jewish property was destroyed by angry crowds. Jewish stores were looted. Synagogues were burned, dynamited or damaged in a dozen cities.

Sounds of breaking glass and shouts of looters died away only near midnight. Hundreds of Jews voluntarily spent the night in jails fearing worse violence as reports of burning and looting continued to come in from many cities.

Those three paragraphs were the first that many in the English-speaking world read of Kristallnacht, a nationwide pogrom that killed dozens of Jewish people and led to the systematic persecution and murder of six million.

During two decades as a foreign correspondent, Lochner filed stories about the rise of the Nazis and knew long before many Americans had heard of Hitler that Germany was headed for war. Before the U.S. entry into World War II, he was among a handful of journalists credentialed to cover the German army in battle. He also managed to tick off Joseph Goebbels, the propaganda minister for the Third Reich, and was interned by the Germans following the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Lochner returned home and wrote a book detailing the rise of the authoritarian regime, in which he eschewed his wire service objectivity and let his emotions flow: “I want the reader to feel as burning an anger as I do at the perversion of civilization that Adolf Hitler is trying to foist on an unwilling world.”

• • •

Lochner was the son of German immigrants — his father was a Lutheran minister — and he grew up in Milwaukee speaking their native language at home. He went on to study journalism at the UW, after switching his major from Greek and Latin, and his senior thesis was on Wisconsin’s primary elections. He was active on campus as director of the German Glee Club, secretary of the junior class, a writer for the Badger yearbook, a Daily Cardinal reporter, and a member of the International Club.

“I place my association with students from all parts of the world ahead of my book learning and technical training I acquired,” Lochner wrote in his memoir, Always the Unexpected. “It was certainly splendid preparation for my later life’s work as a foreign correspondent. I learned to cultivate the ‘international mind.’ ”

As a student, Lochner became active in the peace movement, and in 1909, he attended an international meeting of students in Holland. There, Lochner recalls in his memoir, British journalist and pacifist William Stead, editor of the journal Review of Reviews, told the students that modern wars had become so costly and destructive that countries would never risk “unleashing the terrifying instruments of death which technology has developed.” Stead’s words resonated with Lochner, who had no inkling he would later cover a war that would unleash instruments of death that killed millions of people.

Later that year, Lochner graduated, and he served as editor of the Wisconsin Alumni Magazine (the predecessor of On Wisconsin) for six years. He continued to travel abroad and play an active role in international pacifist organizations, including working for auto tycoon Henry Ford’s failed Peace Ship expedition to Europe in 1916 — experiences that he said influenced his work as a journalist in Germany. “I could never persuade myself that any nation is made up of preponderantly bad people,” he wrote.

His first wife, Emmy, died in 1920, a victim of the Spanish flu epidemic, and in 1921 Lochner moved to Berlin, where he later met and married a German woman, Hilde De Terra. He wrote for a labor press service and freelanced stories to daily newspapers and trade union publications. He also worked as a literary agent for Maxim Gorky, helping the Russian writer find a publisher for his books in Japan.

• • •

Joining the Associated Press in Berlin in 1924 was a dream come true.

“It was Big League journalism whose gates I had crashed. I was now working for the world’s largest news-gathering association, whose daily dissemination of information covered events in every corner of the globe and was read by millions of readers,” Lochner wrote.

As a reporter for the AP in Berlin, and later its bureau chief beginning in 1928, Lochner’s words and photographs documenting the rise of the Third Reich were transmitted around the world. He interviewed Hitler shortly after his release from prison in 1925 and the publication of Mein Kampf, the first of many interviews as he began his rise to power.

Whether by cultivating sources, old-fashioned shoe-leather reporting, or assiduously reading German newspapers and periodicals for tidbits of information that could lead to a bigger story, Lochner was adept at his job — one that became more difficult when Hitler became chancellor in 1933. All German journalists needed government- issued permits to work and could lose them for writing or saying anything not in line with the Nazi regime. Losing a job and livelihood at a time when much of the world was in an economic depression meant there were few dissenting voices in Germany.

Many newspapers closed and publications that remained all printed the same news — hand-fed by Goebbels and the propaganda ministry. Foreign journalists working in Germany faced restictions that were not quite as draconian, but they were kept under surveillance — their phones tapped, mail opened, and conversations monitored. A daily terror was suffocating Germany, and Lochner witnessed Brown Shirts beating people in the street. He heard the anguished cries from Gestapo headquarters on Berlin’s Prinz Albrecht Strasse. He repeatedly requested to visit concentration camps — pleas that the Nazi propaganda office rebuffed.

In the book Breaking News: How the Associated Press Has Covered War, Peace, and Everything Else, a chapter about foreign correspondents describes the difficult position Lochner often found himself in: “Reporters in Nazi Germany had to walk a tightrope — especially important for news agency staffers because of their thousands of clients — in balancing the need to cover the story with maintaining access to officials and avoiding expulsion. Almost inevitably, there were accusations, which AP consistently fought, that Lochner was pro-German.”

In 1939, Lochner won the Pulitzer Prize for his coverage, which often went without a byline, as was the custom for the wire service. When he returned to the United States to pick up the award that June, he visited his hometown and stopped by the Milwaukee Journal. Staffers in the newsroom asked Lochner where and when Hitler would strike next. Though Lochner’s comments were off the record at the time of his visit, a story the Journal published on October 24, 1942, recounted the AP newsman’s prescient remarks: Hitler probably would not make a move until late August, and the crisis might involve border disturbances or trouble concerning a minority of Germans living in another country. He also told the newspaper’s reporters and editors not to underestimate Hitler.

After Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, under the pretext of retaking land disputed between the two countries, Lochner was among the foreign journalists who followed German troops as they swept through Poland, followed by Denmark, Holland, Belgium, France, Yugoslavia, and Greece. He cabled thousands of words from the front lines and witnessed the French surrender in June 1940 in Compiègne — in the same rail car where Germany had signed the armistice that ended World War I. He was in Paris when Nazi troops marched down the Champs-Élysées.

• • •

Lochner knew his days working freely in Berlin were numbered once Germany declared war on America, but he didn’t think they would come to an end until spring 1942 at the earliest. On December 7, 1941, he was dining with top Nazi officials in Berlin when a telephone call from New York interrupted his dinner with an urgent message: Japan had bombed Pearl Harbor and the AP needed reaction from German officials. Lochner returned to his dinner companions, asked questions, scribbled some notes, and phoned them in to the bureau. Two days later, the FBI arrested German newsmen in the United States. He knew, under the German system of reprisals, American journalists in Germany faced a similar fate.

The next day Lochner showed up for the daily press conference at the propaganda ministry, where a Nazi official told him and the other U.S. journalists to go home, which meant house arrest, until further notice. But Lochner didn’t go straight home — this was news, and he needed to file a story. He wrote and sent his last Berlin dispatch, called the city’s other AP journalists and told them not to come into the office, and thanked the bureau’s German staff.

Lochner was among 115 Americans interned for almost five months at a hotel near Frankfurt, unable to file any stories home. In a scrapbook, now housed among Lochner’s papers at the Wisconsin Historical Society on the UW campus, the newsman affixed souvenirs of his internment at a chateau in Bad Nauheim. Black-and-white photos show prisoners performing daily calisthenics, and a pamphlet lists classes Lochner and his fellow internees taught at the “University in Exile” they established to stave off boredom. (His subjects were American geography and German military history.)

“Lochner is behaving in an especially contemptible way. His attacks are directed above all against German propaganda and he aims at me personally,” a frustrated Goebbels wrote in a May 19, 1942, diary entry. “I have never thought much of Lochner. We made too much fuss about him. We can now see what happens in time of crisis.” (The diary was found in the courtyard of the Reich Ministry of Propaganda in Soviet-occupied Berlin in 1945, and Lochner was the one who did the translation after its discovery.) The propaganda minister was furious that while German journalists wrote what they were told, he couldn’t control foreign reporters.

By late May, the Germans released the American reporters in a prisoner swap.

After the War

- Lochner covered the trials of Nazi war criminals in Nuremberg, the home of his ancestors, before retiring from the AP in 1946. Thus, Lochner had a front-row seat to Germany’s rise from the ashes of the First World War, the ascension and downfall of Hitler, and the terrible destruction at the end of World War II.

- He returned to his alma mater in 1955 to pick up an award for distinguished achievement in journalism at a banquet celebrating the golden anniversary of the UW’s School of Journalism. Six years later, he came back to Madison to receive an honorary doctor of literature degree. He lived out his last years in Germany and died there in 1975.

- Lochner’s son, who moved to Berlin with his family at age five, later helped his father cover the 1936 Berlin Olympics for the AP and was a member of the U.S. occupation forces in Germany after the war. As a translator, Robert Lochner worked with John F. Kennedy, preparing the president for his historic visit to West Berlin in June 1963. He was the one who coached Kennedy on the proper pronunciation of German phrases, including “Ich bin ein Berliner.”

• • •

When Lochner returned to U.S. shores on June 1, 1942, an AP colleague met him at the dock and slapped him on the back with the greeting, “What about Germany?” For the next 30 days, the question was repeated with increasing insistence from colleagues who thought he should write a book about his experiences there. Lochner hesitated, because the material he was able to bring home from Germany was incomplete and, in a way, he felt he was too close to the events that took place during his more than two decades in the country. But he ultimately decided the task was too important, and he finished work on it five months later.

“I had to assume that a copy of such a book would fall into Nazi hands — in fact, I hope it will. I know the methods of Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels, but I can face, with considerable equanimity, his efforts to discredit it,” he wrote in the foreword to What About Germany?

The book succinctly and eloquently outlined how Hitler managed to take over an entire country and twist Germans to subscribe to his obscene ideas, and it examined why no one stopped the dictator before it was too late.

Hitler recognized that the common man can grasp an idea better if it is presented to him in concrete symbols rather than abstract, Lochner wrote. And the dictator knew that in order to “remain virile,” a movement needs not only its own ideology but an opponent against whom it can match wits (Jews and Communists in his case). He also had a remarkable faculty for being all things to all people.

“Hitler merely had to unleash the proper emotions in each crowd, show sympathy and understanding for its problems, and the case was won,” Lochner wrote. “Apparently no one bothered to expose the inconsistencies in his arguments.”

Lochner returned to Europe in 1944, this time reporting on American troops as they fought against the German army he had followed into battle just a few years earlier.

“I had gnashed my teeth many a time in impotent rage when I saw how Hitler was overrunning Europe,” he wrote in his memoir. “Now I was retracing my steps, this time with an army determined to restore freedom to Europe. It made all the difference in the world to me.”

Meg Jones ’84 is a reporter for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel and wrote about Louis Lochner in her book World War II Milwaukee.

Published in the Summer 2017 issue

Comments

Richard Henry Burns December 5, 2024

Louis Lochner’s connection with the Goebbels Diaries is epecially pertinent in 2025-2025; the transition is eeriely similar.