Madcap UW Writer Makes History in a Model T

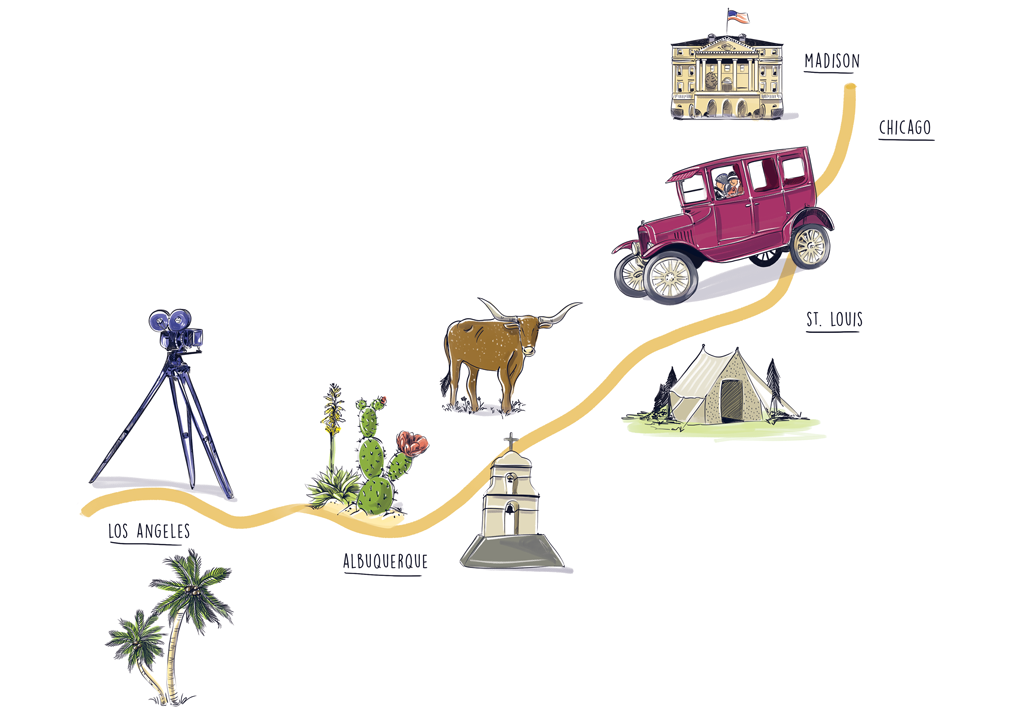

Emily Hahn ’26 opened readers’ minds by writing about her journeys across Africa and Asia. But her first adventure began with her college roommate, an old Ford, and 2,000 miles of uneven road.

Today, the Great American Road Trip is a common rite of passage for college students and graduates. But in 1924, before there was an Interstate Highway System, interstate automobile travel was a rare adventure. That year, two Badgers undertook a special cross-country drive that made headlines and history — and forever altered the trajectories of both travelers’ lives.

But first, let’s back up a bit.

Emily “Mickey” Hahn ’26 was one of the most prolific and adventurous writers to graduate from the University of Wisconsin, yet she’s also one of the least remembered. I first came across her name by accident during my final weeks as a science writer at the College of Engineering in 2011. I stumbled on a timeline buried deep in the website of the materials science department and noticed this tidbit: Emily Hahn, first female graduate, 1926.

No one else in my office had heard of Hahn, and I set about investigating her. What I found astonished me. Starting in the 1920s, Hahn traveled the world and worked for more than six decades as a correspondent for the New Yorker. In 1931, she hid herself in a crate to sneak across borders into the Belgian Congo, and she spent most of World War II in Japanese-occupied Shanghai. She split her later life between New York and London, and she wrote more than 50 novels, memoirs, and biographies, many of which are still in print.

Hahn poses with her pet gibbon, Mr. Mills, in Shanghai. Courtesy of Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana

I was leaving the College of Engineering to go across campus and obtain a master’s degree in journalism, and yet here was Hahn, who’d built a substantial writing career after earning, of all things, the first engineering degree ever awarded to a female UW student. “I don’t know that name,” the late UW journalism professor James Baughman told me when I suggested that he make a mention of Hahn in his long-running Literary Journalism course. Both of us were genuinely surprised that she’d never made it onto the journalism school’s radar.

Hahn’s experience at the UW wasn’t something that past generations of university storytellers were especially keen to promote. A Saint Louis native, she originally enrolled at the UW as an art major, and on a whim, she attempted to enroll in a geological chemistry course in the engineering college. She wrote later that the department chair blocked her enrollment and told her, “The female mind is incapable of grasping mechanics or higher mathematics or any of the fundamentals of mining taught in this course.” Indignant, Hahn immediately switched her major to mining engineering and survived the department’s appeal to the state legislature to remove her from the program.

Hahn’s engineering classmates and instructors frequently tested her resolve. “I trained myself to keep very quiet and to maintain a poker face whenever I was in the college,” she wrote in Times and Places, a collection of essays that was first published in 1970 and was recently rereleased under the title No Hurry to Get Home. Over time, though, Hahn did manage to make a few engineering friends, who took to calling her “Mickey,” a childhood nickname that sounded masculine enough for an engineer — and Hahn used it for the rest of her life.

Discrimination wasn’t limited to the classroom. During her sophomore year, Hahn watched with dismay as, one by one, her classmates were offered summer internships and fieldwork opportunities that were considered inappropriate for women. It was her roommate, Dorothy Raper (later Miller) ’27, who unrolled a map of the world and pointed to a solution: Lake Kivu in the Belgian Congo seemed as good a place as any for a summer adventure.

But before embarking for the Congo, the roommates decided to take a practice trip to Albuquerque. Miller suggested they drive south, stay with her uncle for a while, and then finish the trip with a quick jaunt over to California to see the Pacific Ocean. Hahn’s biographer, Ken Cuthbertson, describes Miller as “outgoing, energetic, and athletic; she was a competitive swimmer,” and Hahn also called her “enterprising.” The only daughter of a newspaper columnist in Cleveland, Miller didn’t hesitate to petition her parents for $290 to purchase a Model T Ford. Miller then spent the spring teaching Hahn how to drive in the “gentle, glaciated hills of the [Wisconsin] countryside, past grazing cows and farmhouses.”

However, not everyone was supportive. “Why do you talk all the time about getting away?” a date asked Hahn not long before the trip. “Isn’t Madison good enough for you?”

“Madison’s all right, I guess, but no one place is good enough,” she replied. “I want to get around. I want to see things.”

• • •

In 1903, Horatio Nelson Jackson and Sewall Crocker took 63 days, 12 hours, and 30 minutes to complete the first-ever American cross-country car trip, driving from San Francisco to New York. Twenty years later, most travelers were still unaccustomed to moving long distances by car. Most American roads were still unpaved, highways were not yet numbered, and the country’s first “motor hotels” wouldn’t open until 1925.

Yet the concept of Hahn and Miller’s driving trip wasn’t quite as radical or treacherous as it seemed to Hahn’s sophomore date. Before the roommates’ quest, Luella Bates had already gained a modicum of fame in Wisconsin as the “first girl truck driver” after she was hired by the Four Wheel Drive Auto Company in Clintonville. And Jazz Age Americans were far more captivated by airplanes than automobiles, anyway; female pilots like Bessie Coleman and Lillian Boyer were barrel-rolling their biplanes and walking on the wings (literally) when Hahn and Miller let their boyfriends haul the last of their luggage into the Model T. However, none of this is to say that what Hahn and Miller did in 1924 was simple or easy. In fact, what interests me most about their adventure is that it was encouraged and financially supported by their parents — and yet was still considered audacious enough to attract newspaper coverage in the Albuquerque Morning Journal.

The roommates departed Madison on June 19, 1924, and made their way first to Chicago and then Saint Louis to see their families. They’d converted the back of the Model T into a fold-down bed — complete with a mosquito net — and as they tried to sleep in a relative’s yard, Hahn’s young cousins kept peeking in through the windows to spy on them. Finally, the women broke free of their required visits and got out on the open road and headed south.

“On our way, on our own, on the road,” Hahn recounted saying to Miller as they skidded along rain-soaked country lanes, taking more than a few curves too fast through rural Missouri. When they didn’t sleep in the car, they stayed at “tourist camps,” which were just gated fields with outhouses. Once, a local sheriff tapped on their car window as they slept and insisted they relocate in front of his own house where he could keep an eye on them. In the morning, Hahn and Miller woke up with a crowd of locals staring at them.

They pressed on, navigating bumpy roads and regularly quieting the Model T’s hissing radiator with buckets of water. The roommates named the Model T “O-O” in honor of all the times the car made an odd noise and prompted them to exclaim, “Oh-oh!” After negotiating a mountain pass and testing the limits of O-O’s radiator and brakes, Miller and Hahn finally arrived in New Mexico on July 6 in mixed spirits. “I must be wrong to recall the tour as long,” Hahn wrote. “Even in 1924 it was not a matter of months to drive to Albuquerque from Saint Louis. Nevertheless, that is the impression I have kept.”

After six days in Albuquerque, the roommates pressed onward to Los Angeles to briefly glimpse the ocean as planned, driving through the desert mostly by night. But the trip finale was anticlimactic, wrote Hahn. By then, Miller was homesick and O-O was developing mechanical problems. “Might as well start back to Albuquerque,” Hahn recounted Miller saying as they watched blue-green waves crash against the rocky shore. “We’ve seen the Pacific.”

• • •

The drive west was the first but far from the last time that Hahn garnered public attention for her travels. When the roommates set out for New Mexico, they were almost certainly aware of some of the famous American women who’d trail-blazed before them, such as Wisconsin-born explorer and museum curator Delia Denning Akeley, along with others who circled the globe and then made money giving public lectures about their adventures.

Later in life, the “lady traveler” persona became a devil’s bargain for Hahn, and she chronically struggled to get New York critics to take her work seriously. Her first major book, Congo Solo, originally exposed the polygamous lifestyle and cruelty of a prominent American medical missionary, but her publisher was wary of a lawsuit and edited the book to instead emphasize Hahn’s challenges as a woman traveling in Africa. Reviewers dismissed the result when it was published in 1933. Kirkus Reviews called it “utterly unconvincing in so far as the human equation is concerned.”

Some 54 books and hundreds of articles and short stories followed, covering diverse topics ranging from biographies to natural history, from the diamond trade to zoos, cookery, and communication with animals. But even her 1997 obituary in the New York Times was headlined “Emily Hahn, Chronicler of Her Own Exploits, Dies at 92,” which strikes me as unfair. It does little justice to Hahn’s extensive bibliography or her serious reporting on international politics on three continents. But her legacy does reflect that Hahn eventually recognized that to sell her work, she had to play up her more audacious angles. For example, her most lasting success, China to Me, highlighted her years as an opium addict in Shanghai and her romance during World War II with a married British spy, who later became the father of Hahn’s two daughters.

Hahn with her two daughters, Amanda and Carola. Courtesy of Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana

But long before Africa and China, there were Albuquerque and California. And that’s where the UW roommates’ paths began to diverge. In her later writings about the trip, Hahn was quick to juxtapose her own New Woman persona with Miller’s more traditional outlook. In particular, Hahn was critical of Miller’s boyfriend, who sent letters for Miller to pick up at every town along their planned route.

“Letters in general were an intrusion, I felt, on this otherwise wonderful existence, reminding me that I had not always been free, that I would someday have to go back to my past,” Hahn wrote. She added that Miller’s “life wasn’t affected by the trip in any serious way, though no doubt it altered a few details for her … She married an Albuquerque man instead of [her college boyfriend], but what’s the difference really? If that’s the way you’re going to be, that’s it. Why, by the time I actually got there — to Lake Kivu [in 1931] — [Miller] already had two children.”

It’s easy to buy into the myth of Miller and Hahn as opposites, to make the practical Miller a duller foil to the risk-loving, adventuresome Hahn. Yet there’s no question the road trip was originally Miller’s idea, and so perhaps she knew what she was doing all along. After all, Miller effectively harnessed her plucky roommate’s energy to get exactly where she wanted to go: New Mexico, where she began to lay the groundwork for a new life. Miller fell in love with Albuquerque during the trip, and after finishing her UW degree, she spent the rest of her life there.

The drive was also an important moment for Hahn’s budding sense of herself as an adventurer. “My first trip West was a tremendous affair,” Hahn wrote. “I don’t think I ever got so steamed up again, not even when I went to Africa or China.”

After returning to Madison, Hahn completed her mining engineering degree and landed a job with a petroleum company in Saint Louis, which she appeared to accept with a sense of resignation rather than pride. Though she did successfully become an engineer, she didn’t stay one for long. One night after work, she heard that fellow UW engineering student Charles Lindbergh x’24 was attempting to fly across the Atlantic. She made a bet with herself that if he made it, she’d quit her job and become a writer. When The Spirit of Saint Louis landed in Paris the next day, she did just that and bought a ticket to New Mexico.

Hahn wanted to say hello to her old friend before embarking on her next adventure.

• • •

I carried Hahn’s name with me through graduate school and into another campus writing job, this time at the Wisconsin Alumni Association. There, I introduced her to my editor, who put her on the list of names to be included in the new Alumni Park. You’ll now find Hahn’s words laser-cut into one of the metal benches along the east side of the park: “Let’s not spend money on anything else, except books.”

Personally, my favorite Hahn quip is what she’d say in response to those who asked why she often chose the roads less traveled: “Nobody said not to go.” Those words became my mantra when I, too, finally left Madison. In 2016, I moved to Europe and traveled across a few borders myself — though never while hidden in a crate. I continue to be inspired by Hahn’s fearlessness, along with her prolific work as a writer. And I hope that the Badgers who happen across her words in Alumni Park will now know the answer to the question I first asked almost a decade ago: Who was she?

Sandra Knisely Barnidge ’09, MA’13 writes about travel, history, and culture for a variety of publications. She’s currently based in Tuscaloosa, Alabama.

Published in the Summer 2019 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.